41 Thunderer — Implements of Destruction, Pt. 1

|

| Colt Model 1877 DA revolver — “Thunderer“ |

Implements of Destruction

I’ve been wanting to explore a few murder ballads, in some cases very broadly defined, that sing about weapons, specifically handguns–their allure and their power. The handgun, in addition to being the means of violence–the implement of destruction–in some songs, also can function as a symbolic tool doing some of a murder ballad’s thematic heavy lifting. I want to focus on this.

The handgun in America presents a symbol closely tied to our collective cultural self-understanding (rightly or wrongly). It’s also a social force that demands our collective moral attention on an all too frequent basis. America’s love/hate affair with the handgun probably launched in the American West in the latter half of the 19th century, when as Bill James has described (pp. 31-32), the territory was being settled, the population was low, law enforcement was minimal, the Civil War had degraded the culture of law and order, and people had access to relatively inexpensive, reliable, and deadly weapons.

The legacy of the West then flourished culturally through mostly idealized presentations in books and films. The “Western” was particularly strong in the mid-century decades. Although its popularity has been in a reasonably steady decline ever since, the American West as an imaginative landscape continues to inform how Americans, and perhaps others, think about a lot of things. The West has been the scene of the crime for several of the songs we’ve discussed here–including Townes Van Zandt’s “Pancho and Lefty,” Marty Robbins’s “El Paso,” and Norman Blake’s “Billy Gray.” The mode of these songs is nostalgia and romance.

|

| “Big Iron” (image courtesy of Mari Mihai, http://cargocollective.com/marimihai) I expect we’ll get to the Marty Robbins classic before too long. |

Murder ballads resonate because they create meaning. Often they eke it out of the meaningless or the irrational. There’s sense-making going on, because the original events stir some things up that can’t always be resolved intellectually. And the songs themselves also present the killers asking these questions. Songs like “Knoxville Girl,” “Banks of the Ohio,” or “Down in the Willow Garden” present reflections on the “I loved her so much I had to kill her” theme that Rorey Carroll, for instance, found so troubling. This paradoxical theme inspired her to write a murder ballad from a different point of view. But, even her song “Head Hung” presented the protagonist’s existential bewilderment at what she found that she was capable of doing. Sometimes the purpose of these songs is to explore how some force beyond our control took over our better judgment.

This leads to bargaining. We bargain with our sense of moral agency and responsibility. There is a prolonged, if often implicit, discussion about moral responsibility going on among murder ballads. Sometimes murder ballads are quite clear about their moral judgment–condemning the killer for his or her actions. Some murder ballads condemn the person killed, or view their death as just punishment for their waywardness or wickedness. Others cast about looking for the right person or force to blame.

Most of the songs in our “Who Killed …” series earlier this year explored this issue. Songs like Mac Davis’s “In the Ghetto,” place the responsibility on society. “El Paso” paints Faleena as the bewitching Mexican maiden whose powers conquer our hero’s better judgment. He both kills and dies for her. Jim White’s noirish “The Wound that Never Heals” alleges that an irresolvable emotional legacy of childhood abuse drives a serial killer. The examples where jealousy or passion take over someone’s will are too many to count. This is all to say that one of the possible outcomes of trying to make sense of it all is the realization that forces greater than anyone’s will or reason bring these tragic events to pass. Sometimes those forces come from within; other times they come from without.

Most of the songs in our “Who Killed …” series earlier this year explored this issue. Songs like Mac Davis’s “In the Ghetto,” place the responsibility on society. “El Paso” paints Faleena as the bewitching Mexican maiden whose powers conquer our hero’s better judgment. He both kills and dies for her. Jim White’s noirish “The Wound that Never Heals” alleges that an irresolvable emotional legacy of childhood abuse drives a serial killer. The examples where jealousy or passion take over someone’s will are too many to count. This is all to say that one of the possible outcomes of trying to make sense of it all is the realization that forces greater than anyone’s will or reason bring these tragic events to pass. Sometimes those forces come from within; other times they come from without.

These themes guns, the West, moral responsibility, and irresistible forces started to percolate as I listened to this week’s featured song, “41 Thunderer” over a few recent road trips. I realized that an occasional series of posts on songs about pistols would illuminate a broader discussion about murder ballads. Each of the songs we’ll take up in these first few posts will press questions about responsibility, agency, and powerful inner and outer forces beyond our control or capacity resist. They will also take us to the West–or at least the Western.

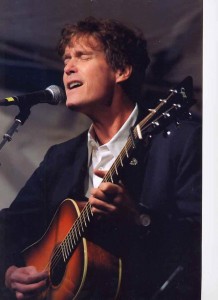

Where to start with Dave Carter?

In the early fall of 2001, I popped Sing Out! magazine’s sampler CD for their September issue into my disc player, and heard Dave Carter and Tracy Grammer’s performance of “Tillman Co.” (lyrics here). Carter’s lively and rich lyrics crackled with Southwestern imagery and Biblical themes, and didn’t compromise or hedge. I’m sure I had a copy of Carter and Grammer’s drum hat buddha by Christmas, and found more riches there. I mention this because “Tillman Co.” first exposed me to Carter’s music and because “Tillman Co.” set the imaginative landscape that made “41 Thunderer” all the more powerful for me, even thought their stories are not tied.

In the early fall of 2001, I popped Sing Out! magazine’s sampler CD for their September issue into my disc player, and heard Dave Carter and Tracy Grammer’s performance of “Tillman Co.” (lyrics here). Carter’s lively and rich lyrics crackled with Southwestern imagery and Biblical themes, and didn’t compromise or hedge. I’m sure I had a copy of Carter and Grammer’s drum hat buddha by Christmas, and found more riches there. I mention this because “Tillman Co.” first exposed me to Carter’s music and because “Tillman Co.” set the imaginative landscape that made “41 Thunderer” all the more powerful for me, even thought their stories are not tied.

Carter’s lyrics draw heat and stark sunlight from the most arid of Western deserts and they refresh with inspiration from symbolic wells and rivers that baptize and transform the truth-seeker. Carter’s mother was part of a charismatic Christian church tradition, and his lyrics resonate with the power of those ancient themes, however much he may have personally moved away from the creeds and confessions to which they are attached. Carter’s lyrics re-enchant the landscape with a Bible Belt eye and an post-modern American mysticism born of broad vistas and hot places.

|

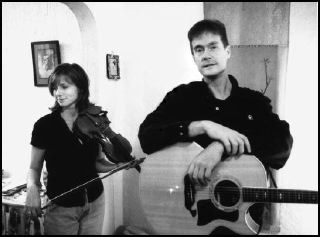

| Tracy Grammer and Dave Carter |

Tragically, Carter died of a heart attack less than a year after that Sing Out! release, and just a few weeks shy of his fiftieth birthday. Tomorrow (August 13) would have been Carter’s 61st birthday. In some respects, he was a late bloomer on the Folk/Americana scene, but his songs were already gaining him appreciation as a songwriter’s songwriter. Rob Weir attests, “If you encounter a list of the greatest songwriters of the 20th century and Dave Carter’s name not on it, walk away.” Carter’s singer-songwriter peers showed their esteem in many moving posthumous tributes and covers of his work. Carter created a tremendous amount of music in a very short period of time, and was by no means done getting that work out there and finding more beauty to send out to the world.

It’s an aside, and the last thing I’ll mention before returning to our song, but Carter delivered a fascinating preamble to a performance of “Farewell to Saint Dolores” at the Sisters Folk Festival in 1999. With a mix of humility and an awareness of his gifts–but more importantly, I think, with a sense of responsibility for a creative trust that he felt had been placed in him–he mentions that he had started to feel like he was channeling Townes Van Zandt. Van Zandt had died a few years prior, at the age of 52, and Carter felt Van Zandt’s inspiration in starting to write a number of “Farewell” songs.

Now it’s stand and deliver

drum hat buddha starts off auspiciously with the line “Common cool, he was a proud young fool in a kick-ass Wal-mart tie,” and goes on from there to many wonder-filled places, with songs of prophets and losses, love and the open road. “41 Thunderer” is a standout, though, for its stately, sober power and the dark forces that pulse within it. Among the livelier and more overtly clever songs on the album, it’s a decided change of tone–as though a curtain gets pulled away to reveal an underlying truth not as playful as the rest. Here it is as it appears on the album:

You will have noticed by now, if you didn’t notice in the lyrics at the top of the post, that there’s no explicit violence in this song. You may cry foul, and for two reasons: first that the violence is implied or anticipated; and second, perhaps, that Carter pulls the punch–at least depending on how you interpret the “stand and deliver, and fire in the hole” moment in the chorus. Nevertheless, it is very clear that we are poised upon the edge of violence, and brought there by a complicated mix of seduction, temptation, and broad-sky desert desperation. The gun is loaded with sex and violence, and it’s going to go off. This is what is important for now. Our hero has fallen from “the narrow and straight.” The rest is consequences.

Next up

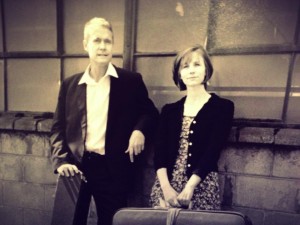

In the next post, we’ll learn some of the story behind the song. I had the great good fortune to make contact with Tracy Grammer in preparing this post. She very graciously agreed to a virtual interview about “41 Thunderer.” At Grammer’s recommendation, I also reached out to Carter’s sister for further background and thoughts about it. So, be sure to stay tuned for the next post for some unique insights into the song and the dynamics of performing it. Plus, I’ll attempt to “redeem” myself for murder ballad boundary stretching by connecting to spectacular Carter contribution to the mainstream of the tradition.

In the meantime, I invite you to join me in raising a glass tomorrow to Carter’s memory and raising the volume on some of his songs.

|

| Dave Carter and Tracy Grammer (photo 2000 by Mark Rabiner) |