Richard Polenberg: HEAR MY SAD STORY ….

Richard Polenberg

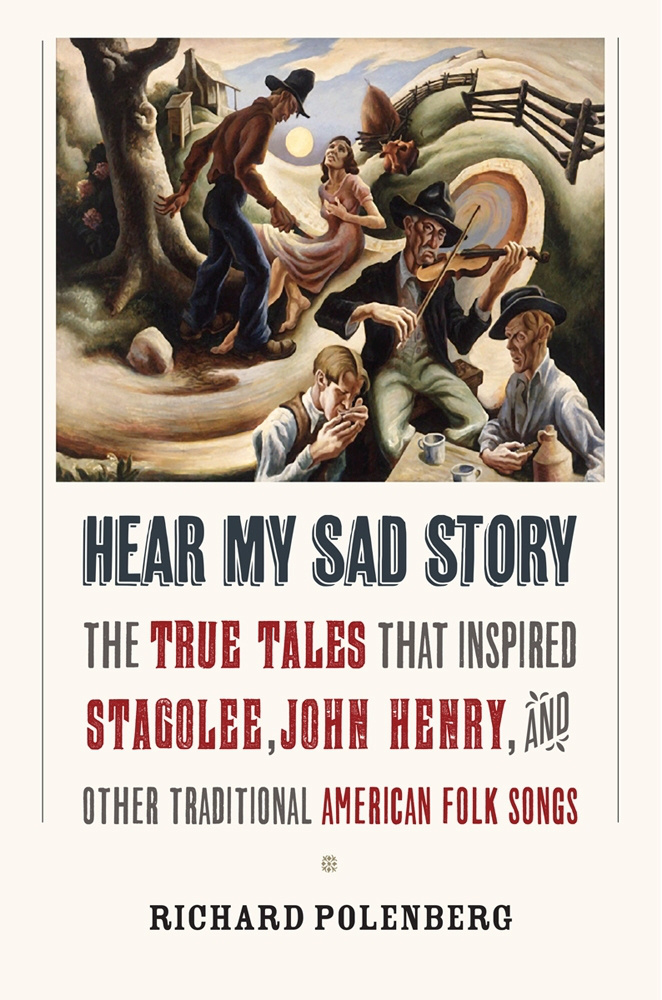

HEAR MY SAD STORY: The True Tales That Inspired Stagolee, John Henry, and Other Traditional American Folksongs

Cornell University Press 978-0-5017-0002-6

In 1966 Phil Ochs remarked, “Before the days of television and mass media, the folksinger was a traveling newspaper spreading tales through music…. Every newspaper headline is a potential song.” Long before and after Ochs made that remark, commentators referenced folk music as “musical newspapers.” For every song that springs from a writer’s fertile imagination, there is at least one inspired by real-life events and commemorated in ballads, broadsides, song-poems, slogans, and twice-told tales. Those events are the subject of a new book by Cornell history professor emeritus Richard Polenberg, who adds a twist: the ways in which folk songs “improve” upon reality and help construct legends that may or may not be close to what actually happened.

Polenberg begins with the news – the real-life Lee Shelton (“Stack Lee”), Naomi (“Omie”) Wise, Morris Slater (“Railroad Bill”), and other such characters – and links what history says of these individuals to the songs and legends they inspired. Legends are not the same as myths; they occupy a middle position on a scale with verifiable history at one pole and belief-based mythology at the other. Often, the legends become so well known, though, that a work such as Polenberg’s is necessary to replant the tales in factual soil. Sometimes legends match up pretty well, like Vernon Dalhart’s famed “Wreck of the Old 97,” which some scholars call the first true country music recording; other times great liberties are taken – some of the musical tales of John Hardy, for instance, could be viewed as driving with an expired poetic license. But whether the songs hew close to the truth or spin yarns of gossamer-style veracity, Ochs was right: those songs became traveling newspapers. In essence, they helped write history as it is perceived, whether it actually happened that way or not. Folk music has been an important factor in how legends emerge, spread, and ingrain themselves in American culture.

Hear My Sad Song consists of twenty-one mini narratives that focus on individuals, four that deal with occupations (cotton mill workers, chain gangs, miners, and New Orleans prostitutes), and two that probe disasters (the Titanic and the boll weevil infestation of the 1920s). Folk songs share an affinity with the tabloid press in the sense that neither can resist a good murder, hence sixteen of Polenberg’s chapters deal with sensational homicide cases, sanguinary rogues, and those who may or may not have been killers (like Joe Hill and Sacco and Vanzetti). He bookends his chapters with a prologue and epilogue that use cowboy poet/songwriter Frank Maynard (“The Dying Cowboy”) as his foil.

Polenberg loves folk music, but the book focuses more on history. If you do the math, you can see he’s bitten off quite a lot for 304 pages. Each of the 27 chapters is self-contained, hence Hear My Sad Story is actually a series of short stories (8 to 11 pages) only loosely built around his musings on Maynard. It’s the kind of book that’s best read one tale at a time, preferably with a soundtrack cued. The short chapters tend to be heavy on names, investigations, and court proceedings, with music appearing as annotation rather than discussed in great depth. In my view, the book could benefit from saving material not specifically focused on individuals for a second volume. Pruning a few chapters would have provided more space to tell stories in greater and more leisurely detail, a tact that would improve the book’s flow – in essence, more narrative and less chronicling. Most of this book is illuminating, though there are parts that don’t tell us much. We don’t know, for example, if “House of the Rising Sun” had anything at all to do with New Orleans’ Storyville red light district, thus Polenberg’s chapter, though fascinating, tells us little about the song. On a personal note, I’m more skeptical of Joe Hill’s innocence than Polenberg, yet way more convinced of the validity of Scott Nelson’s research into John Henry.

Book critiques have a way, though, of reflecting a reviewer’s biases just as the book reflects those of the author. If you’re a longtime folk music fan, you may already know the stories behind individuals like Casey Jones or Tom Dula/Dooley. It’s important, though, that longtime fans place themselves in the position of younger folks for whom the history/music/legend nexus is a recent revelation. Polenberg’s book is fine reading on its own, but it might prove invaluable in the classroom. Check back with me; I’ll be test-driving it in my spring seminar on American folk legends.

— Rob Weir