“Oh Father, cruel Father, you will die a public show!”

Our first post this week introduced the murder ballad “Young Emily”. 19th century English folk knew it as “Young Edwin in the Lowlands Low”. Eventually it acquired many other names – all cataloged commonly today as both Laws M34 and Roud 182.

In our introduction you’ll find the basics of its history and narrative, fine examples of the most popular version today (called “The Diver Boy” and born in the Arkansas highlands), and an initial discussion of the key aspect of the ballad we’ll consider this week – making meaning of the father’s cruelty across time and geography. (Click here if you want to read that post.)

If you hit this post first and don’t want to click back, we’ll have more music today that will give you a full-enough feel for the ballad. But if you’re not familiar, you need to know up front at least what I mean above by “the father’s cruelty.”

This song is a murder ballad because it tells a story wherein a father kills his daughter’s lover as he sleeps, in a bed at the father’s inn no less, and then throws him into the river – “down in the lowlands, low.” Why did he do it? Well, that’s open to interpretation – and, as we sail to England to investigate, that question gives us our starting point today.

“Come all you wild young people and listen to my song…”

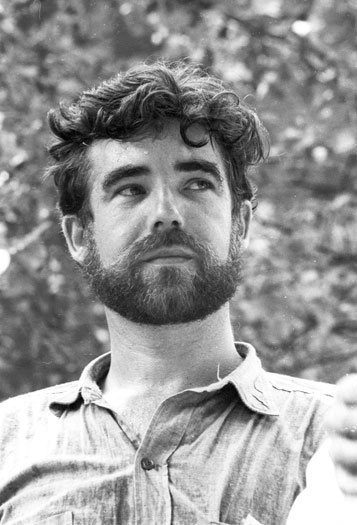

A young Louis Killen recorded a seminal and outstanding version of “Young Edwin” for his 1965 album Ballads and Broadsides. Indeed, it retains quite a few of the elements we see in British broadsides (this one, for example) from the early 19th century. This is most clearly a direct descendant of the ballad before it emigrated to North America.

“Young Edwin in the Lowlands Low” – Louis Killen (Spotify) Lyrics for Louis Killen’s version

Interestingly, between the verse with Emma’s exhortation that Edwin conceal his identity and the one describing her dream, Killen leaves out a verse that is quite common in many other versions. For example, the broadside above has it as…

Young Edwin he sat drinking till time to go to bed

and little was he thinking what sorrow crowned his head.

Said Emma’s cruel father “His gold will make a show!”

We will send his body sinking down in the lowlands low.

Killen’s reason for leaving this verse out is not clear to me, as it helps strengthen the overall narrative. This after all is Edwin’s fatal error – showing off or at least carelessly revealing his wealth while intoxicated. If recording time was a limiting factor for Killen in some way, he might have chosen to trim the song down in this manner as it’s not a truly essential verse – both the first and last verses make it rather clear that greed for gold is the motive.

Perhaps, though, leaving this verse out opens the door (intentionally or not) to a back story that’s not explicit – that the murder is about more than gold. By blurring that part of the narrative, we’re certainly more encouraged read in that Edwin’s identity was discovered by Emma’s father and the murder is about controlling his daughter as much as it is about gaining gold.

Killen’s version does include one element that is fairly common in the versions that I’ve found – Emma turns her father in and has him hung for his crime!

Whether Killen knew or not, the daughter’s hatred for a cruel father who keeps her from her true love is an undeniably powerful element, and one with an arguably universal appeal for young men and women both. I’ll pursue all this a bit further later this week as well.

“Her shrieks were for young Edwin…”

Killen though omits another verse at the end – less common in modern versions – wherein Emma, after losing her love and watching her father hang, goes insane and is committed to Bedlam where she shrieks for her Edwin.

It’s easy enough to see why this part of the ballad might have a hard time surviving into an age when mental illness is less stigmatized than in the early 19th century. Conversely, given that Bedlam was open to visitation by spectators until 1770, the verse makes obvious sense in a British ballad likely written sometime in the half-century thereafter. It would have certainly increased the drama to a listening audience familiar with the idea of seeing the insane as a ‘show’, replacing the real thing with a sort of virtual visit to the asylum.

But then again, maybe precisely *because* of our perspectives on mental illness, when we *do* find Emma’s trip to Bedlam in versions today, it *absolutely* amps up the drama!

Let’s listen to a great example.

We first included Jo Freya’s music in this blog during Ken’s week exploring “Bold William Taylor.” Here now for her second appearance at Murder Ballad Monday is Jo Freya with her lovely and haunting performance of “Edwin in the Lowlands Low” from her 2008 album Female Smuggler.

“Edwin in the Lowlands Low” – Jo Freya (Spotify) Lyrics to Mrs. Hopkins version, collected in 1907 in Hampshire

Seeing that Ms. Freya’s response to our post on her Facebook page about “Bold William Taylor” included reference to her affinity for “Young Edwin”, and knowing this ballad was already in my queue, I took the opportunity to email and ask her about why she sings it and what might be her source. She was most gracious in responding!

Regarding provenance, she’s been singing the ballad since she was fourteen and is not clear on her original source. Interestingly, though musically her performance uses some non-traditional instrumentation, her lyrics are even closer to the those in the traditional British broadsides than Killen’s!

In fact, her version follows quite closely an example collected in 1907 near the southern coast of England, and included in the 1959 Penguin Book of English Folk Songs. Given its publication date in the middle of the second British folk revival and the close correspondence of its lyrics to hers, it seems likely that this version is at the root of whatever performance or recording compelled her as a youth to pick up and keep singing this ballad.

Freya though is *perfectly* clear on *why* she loves to sing it – and her answer gives us even more to think about here!

It’s the missing story that often fascinates me about ballads. Why do her parents hate him so vehemently that they are prepared to murder him? …an excessive way of getting rid of an unwanted or unsuitable boyfriend. So I am always thinking about what may have gone on behind the scenes of this fantastic drama. That in addition to having everything – love, intrigue, murder, and then madness and grief. Oh yes… fab drama.

There is no doubt that Freya evokes fab drama in her performance! As well though, in her comments we see that she perceives an element of the story that isn’t made explicit by a strict reading of the lyrics. The father’s hatred of Edwin may be a deeper explanation than greed for the murder. And, in my opinion, there can be little doubt that this interpretation is justified even if the narrative doesn’t prove it.

Are we to believe that Emma’s father just murders any young man with full pockets who happens to rent a room at his inn, and that he escapes justice every time? Or, had he been thinking about doing it for years and it just so happened that Emma’s true love Edwin lucked out in being the one Daddy finally picked as his target for larceny and decapitation?

You see my point, I hope. If we give any thought to the story, we have to assume Emma’s parents knew of Edwin, even if they’d never met him. She’d been waiting for him for seven years, presumably never courting with another man by her or her father’s choice. In seven years, don’t you suppose she would have let slip to *someone* the reason – that Edwin was out there saving every coin so that they could get married? That’s not the kind of thing a ‘feeling lover’ keeps quiet. Why else would Edwin need to keep his identity secret when he took a room at her father’s inn?

Still, the lyrics don’t plainly tell it.. We get to fill in the blanks on this one. As always, when such spaces are left open in such a compelling way, it gives the ballad wings to pass through generations and across oceans.

Was this hidden back story intentional on the part of the person who wrote the ballad? We can’t know – but I suspect not, given the first verse in these traditional English versions. It’s a tale “concerning gold which I’ve been told does lead so many wrong.” It’s a morality play about greed, if you take it at face value.

But Daddy kills his daughter’s lover, and that’s intense. It’s precisely the “missing story”, as Freya puts it, behind that horror that really can’t be ignored by imaginative folk.

A creative imagination can fill in accidental voids in a narrative just as wonderfully as it can those left by design. Original intent matters *not at all* to the generations, as long as each can make the meaning they cobble together work deeply enough for them.

Coda – “Come all you feeling lovers…”

So, it doesn’t matter whether the 19th century writer of this ballad meant to paint only greed as the impetus for Emma’s father to murder Edwin, or to suggest instead that paternal control of a daughter was the dominant motive. Each generation of singers and listeners gets to figure out the motive for themselves. Ok. So what?

Good question. Isn’t that conclusion the musicological equivalent of moral relativism? I imagine some squint-eyed, long-haired guitarist with the munchies – “A ballad’s meaning is whatever we think it is, man.”

So what? So, it’s not quite that simple and I think even we amateurs can take it a bit further; maybe do a bit better. In the next posts I’ll do some musing about how the archetype of the ‘cruel father’ might have played out over time and space, keeping in mind a ballad’s ‘inherent instability in meaning.’ It seems to me the cruel father is the key to this ballad’s ability to flourish in different times and places.

Let’s end today though with more music. We’ll stick with English versions here and move to Irish then American ones in the last two posts.

Of course Steeleye Span, as they would, cut a British folk-rock version of this sordid and classic tale of greed and murder. How could they resist? And how can you resist giving it a listen?

But to close, we should go back to deep roots – or as close as we can get anyway. Some of you already know of Harry Cox, one of the finest sources for traditional English folk music in the 20th century. But whether you know him or not, have a listen to his version of “Young Edmund”.

As soon as you can get past the age in his voice, you’ll hear the timelessness of his song.

Thanks for reading and listening folks. There is some great music to come later this week, so I hope you’ll stay tuned!