Legend and Outlaw: Jesse James and the Ballad Tradition

Legends

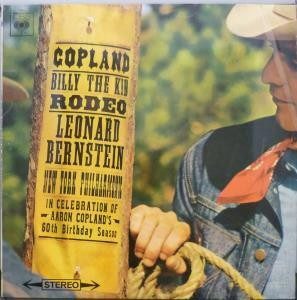

Among a few adults who spooked me when I was a girl (my school bus driver, who kept a bottle in a brown bag beneath his seat; a guy at the car wash who sometimes shut the system down when we were in the middle of a soap cycle), two outlaw figures occupied a place in my head reserved for danger: Billy the Kid and Jesse James. They fascinated me as much as they spooked me, but even my fascination was riddled with something troubling I was ill equipped to define or distill. I used to lay on the living room floor next to the stereo cabinet and thumb through albums, looking for the cover that thrilled me: Leonard Bernstein conducting the New York Philharmonic in Copland’s Billy the Kid. It resembled a wanted sign.

The Philharmonic didn’t particularly fascinate me. Neither did Leonard Bernstein. It was the cover image that captivated me – the red bandana and the jean jacket, the rope coiled in the hand, the fake wanted sign, the intimation of danger. Sometimes I listened to the album, which led to disappointment. I couldn’t understand why the cover scared me but the music didn’t. I felt cheated. Still, I pulled that record out every time I opened the stereo cabinet. There was intrigue I couldn’t quit.

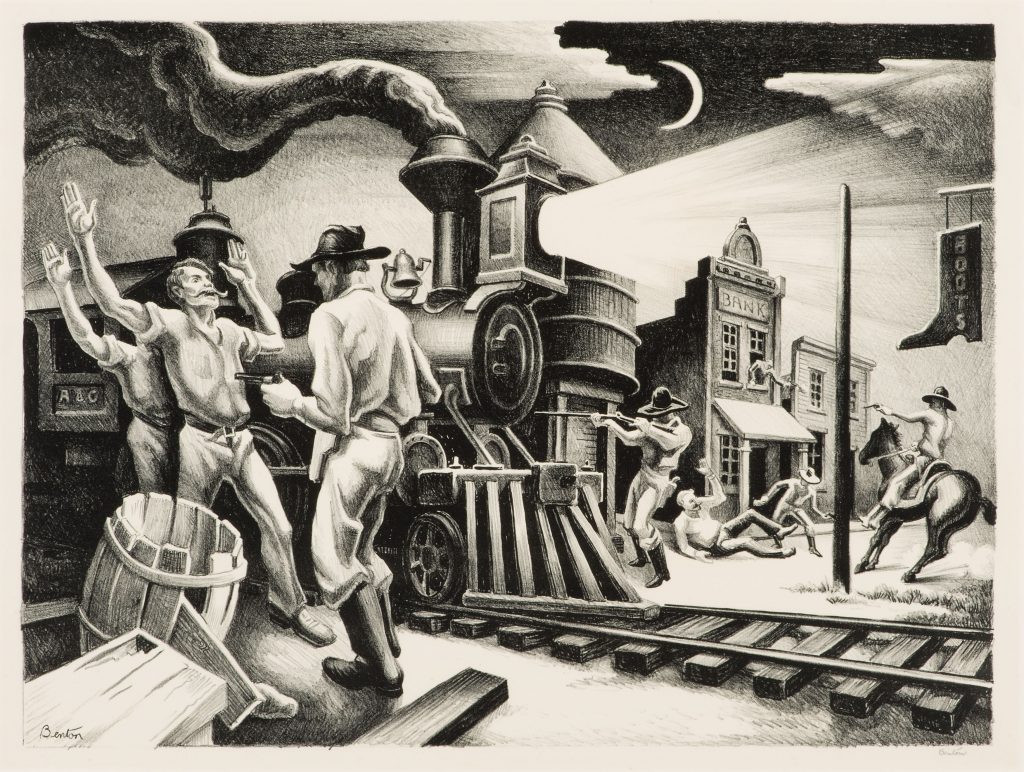

I conflated Billy the Kid with Jesse James, about whom I knew maybe a little bit more. This was the mid or late 70s, and though those outlaws were dead, I didn’t believe it. My grandpa’s grandpa lived in St. Joseph, Missouri and worked the railroads the same years Jesse James robbed them. I was that close to outlaws – close enough I thought they were still alive, hiding in my stereo cabinet.

A few years after my confused fascination with the Philharmonic’s album cover, Paul Kennerley released his concept album, The Legend of Jesse James (1980). That album collects the kind of stories I expected to find in the grooves of the Copland album. It simplifies Jesse James’s life, and that simplification both mars and sustains the album. It is a necessary simplification for the success of the album, but it perpetuates an old mythology. By emphasizing a chivalric tradition, Kennerley obscures the racism tangled in James’s life.

Jesse James, of course, was a far more complicated man than I imagined when I was eight. He wasn’t really even of the West. He was from Missouri, and though Missouri is hard to pin, James was united with the Southern cause, and his crimes were inexorably intertwined with that cause.

Kennerley organizes the album chronologically, and the effect is like listening to a soundtrack for a movie or a musical that wasn’t ever made. Plenty of films depict Jesse James, but Kennerley’s album just wasn’t built around one. Nevertheless, he assembled a star-studded cast. Levon Helm has the lead role, singing as Jesse James. Johnny Cash performs as Frank James, Emmylou Harris sings as Jesse’s wife Zerelda, Charlie Daniels sings the part of Cole Younger, and Albert Lee sings the role of Jim Younger.

Something Pure in an Impure World

Emmylous Harris sings the most emotionally resonant songs on the album. Though the album – and the chunk of history it documents – is not awash in tenderness, “Heaven Ain’t Ready For You Yet” is. Here is an achingly beautiful song – a woman singing about the man she loves, though Harris and the song transcend cliché. The assertion, “I shall not slip away,” first attributed to Jesse and later to Jesse’s cousin-turned-wife, mutates in a most lovely way.

I can get lost in this song in the way I used to love getting lost on the living room floor by the stereo cabinet. We kept headphones in that cabinet, and the headphones contributed to (and permitted) a deeply immersive musical experience. Although I have come to appreciate the deep pleasure of sharing musical experiences with others, I used to savor musical privacy. Sometimes – maybe especially when one is young – you need to feel as though you’re the only one who hears something. “Heaven Aint’ Ready For You Yet” is one of those lovely “I’m-Alone-Listening-To-Music” songs.

Harris’s voice widens the camera lens on an album dominated by men. It also offers a purity of emotion I admire. In “Heaven Ain’t Ready For You Yet,” that emotion is love. In “I Wish We Were Back in Missouri,” it’s homesickness. By turning nostalgia into something lonesome and empty, “I Wish We Were Back in Missouri” accommodates some complexity, which the album needs. It also simplifies the picture of Reconstruction (“simple people in a simple land” reveals nothing of the difficulties of that era), though in this way it is faithful to the notion of homesickness, which obliterates what is unpleasant about “home” and replaces it with filtered longing.