Delia’s Gone – A Digital Compendium, 1993 – Present

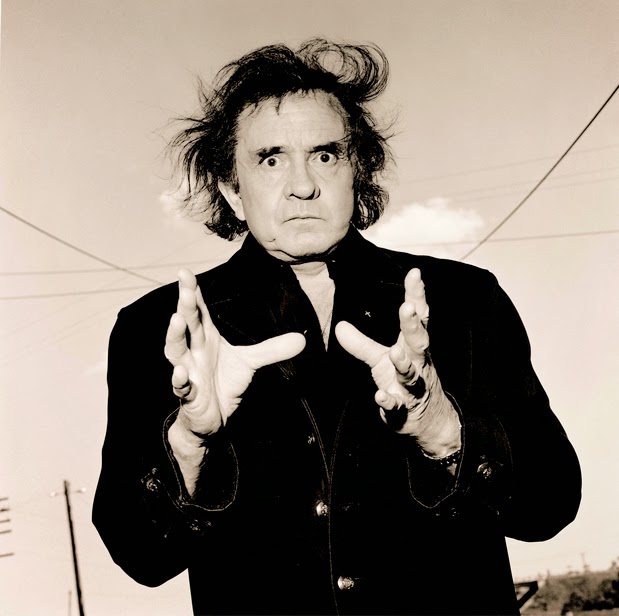

“There is that beast there in me, and I got to keep him caged or he’ll eat me alive.” – Johnny Cash, 1994

Note: This is Part 2 of a two part series on “Delia’s Gone” – See also Part 1

Introduction

Today’s post isn’t about Johnny Cash’s song “The Beast in Me“, but it is all about restraint, and lack thereof. After all, when a man sings about tying a woman to a chair and shooting her with a sub-machine gun simply because she was “lowdown and trifling… cold and mean”, we might reasonably suspect we are dealing with a beast, whether he be in the song or singing it.

Now, our regular readers know that a few weeks ago I posted Part 1 of this digital compendium, wherein we got a solid lesson on the first 90 odd years of the life of “Delia”, aka “Delia’s Gone”, etc. I think we all got something useful from that one, and I hope we can do the same today. But, even if you just find yourself here in Part 2 because of an Internet search about Cash’s version of the song, or Bob Dylan’s, you’ve come to the right place.

Let me suggest though, if you don’t know the history, that you go back to Part 1 and check out the true story behind this super-centenarian African-American bad man ballad, as well as the long string of recordings which led up to its rebirth in the last decade of the 20th century.

Let me suggest though, if you don’t know the history, that you go back to Part 1 and check out the true story behind this super-centenarian African-American bad man ballad, as well as the long string of recordings which led up to its rebirth in the last decade of the 20th century.

It’s a long post. If you check it out, I’ll be happy to wait…

Done? Ok, awesome!

So, you saw all the references to the important scholarship on this and now you know that the ‘beast’ who shot fourteen year old Delia Green in Savannah on Christmas Eve in 1900 was no monster. He was a kid himself; her drunk, fourteen year old boyfriend, Moses ‘Cooney’ Houston. She called him a “son-of-a-bitch” for speaking of her publicly like his sexual property, and pretty soon thereafter he shot her in the groin. And you know as well that the song, which started its life in the American southeast, changed as it traveled around the southern states as well as across the water to the Bahamas by the 1920’s. For the next sixty years, both branches of the ballad grew and diversified, though the Bahamian version eclipsed the American when it became a popular recording in the U.S. in the 1950’s.

Oh, it’s all good; I know you didn’t really go back and read that whole thing. But, I’m telling you – there’s some awesome music in that post, and for the rest of this one I’m going to be referencing some of those recordings as well as details of the true story of Delia and Cooney as if you’re well aware, so be fairly warned. I don’t want to confuse you, but I don’t want to keep repeating myself.

As well, this post is different and stands on its own; even if it is, in part, a continuation of the first discography. But even that line leads someplace new.

As well, this post is different and stands on its own; even if it is, in part, a continuation of the first discography. But even that line leads someplace new.

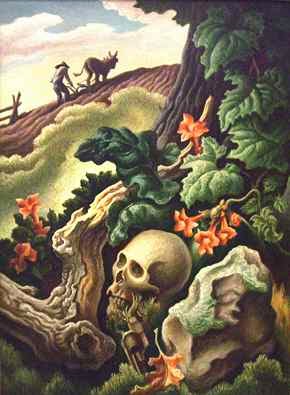

I’ve come to the conclusion, after weeks of listening to this song and reading what others have had to say about it, that “Delia” in the 1990’s and beyond is rather different than she was before. And I think to understand her place today we must look a beast square in the face. And I’m not talking about an armed, drunk teenager or Johnny Cash.

In fact, if you could wait a second this time… I just need to get myself a mirror here before we start… Got it! Good. Thanks.

Now let’s get going. But before we face the monster, let’s hear some music. We’ll pick up where we left off in Part 1.

Bob Dylan – 1993 – “…no middle range…”

In 1993, Bob Dylan brought “Delia” back to popular music where she’d been missing but for a few brief instances since the early 1970’s. Dylan’s World Gone Wrong is full of hard-hitting traditional songs, and “Delia” is one in a trio of murder ballads on the album along with “Stack a Lee” and “Love Henry.” Dylan’s version is a solid mix of Blind Willie McTell’s and Rev. Gary Davis’s, and thus a hybrid flower on the American branch of this ballad. He may not be an integrator on this one, but Dylan’s skills as a traditional confabulator are demonstrated most aptly.

Lyrics for “Delia” by Bob Dylan

Here are Dylan’s comments on the song in the liner notes:

“DELIA is one sad tale – two or more versions mixed into one. the song has no middle range, comes whipping around the corner, seems to be about counterfeit loyalty. Delia herself, no Queen Gertrude, Elizabeth 1 or even Evita Peron, doesn’t ride a Harley Davidson across the desert highway, doesn’t need a blood change and would never go on a shopping spree. the guy in the courthouse sounds like a pimp in primary colors. he’s not interested in mosques on the temple mount, armageddon or world war III, doesn’t put his face in his knees and weep and wears no dunce hat, makes no apology and is doomed to obscurity. does this song have rectitude? you bet. toleration of the unacceptable leads to the last round-up. the singer’s not talking from a head full of booze.”

Other than by choices made in combining two versions to make a new, seamless whole, Dylan adds little of his own interpretation to the traditional performance. Or perhaps it’s more accurate to say that the unique interpretation he weaves in is subtle enough to slip by as if it to seem part of the warp and weft of the original. Certainly McTell’s somewhat jolly approach is gone. But even the sadder, muted approach Davis and his students took is somehow transformed as well. There is a unique pathos to Dylan’s presentation that seems appropriate for a post-modern listener both in relation to the fiction being told and the history that stays hidden. The song indeed “has no middle range.”

Dylan sees “rectitude” as well. Yet, as Sean Wilentz put it in “The Sad Song of Delia Green and Cooney Houston” in The Rose and the Briar – “The truth about Cooney Houston and about Delia Green just turns out to be less clear-cut and even sadder than Dylan suspected.”

Dylan of course attempts to evoke the characters, not the Delia and Cooney of history. In doing so, he benefits from the creative storytelling ways of the blues men, American griots like McTell and Davis. As in the blues versions that inspired Dylan, the singer might be the murderer Curtis, or he might not. Are those last two verses an admission that the narrator is indeed the killer, or do they indicate that the narrator was one of Delia’s lovers and thus, one of the reasons that Curtis shot her? Perhaps the voice simply shifts as it sometimes does within a traditional ballad from narrator to killer. In any case, a master raconteur like Dylan would not let such ambiguity persist in a song accidentally, particularly when he was already drawing two sources together as an editor. No, there is an “I” in this song who purposefully is at once storyteller, listener, jealous ‘other’ lover, and murderer – though, interestingly, not Delia, the victim.

But when I hear Dylan sing it, I find I can’t hide from the gaze of any of them – whether he meant it to be that way for me or not. (Where’s that mirror? Oh, here we go…)

And, rectitude? Well, I guess you’ll have to decide for yourself. More on this below, but let’s now get to the Man in Black.

Johnny Cash – 1994 – “I hear the patter of Delia’s feet…”

Cash inherited and upgraded the Bahamian version of “Delia’s Gone.” As you’ll remember from Part 1, the refrain “one more round” marks this unmistakably as descended from the islands. That makes the early 1990’s an interesting period of transition for this ballad. Of course, it’s always been a ‘dweller on the threshold’, born in the passage between traditional and modern balladry, sailing the waters to the islands and back to the mainland, and translating easily from African-American to Anglo-American idioms. And, with Cash’s recording right after Dylan’s, both branches crossed over Time’s fence at once, strong and healthy, to drop seeds in to another century.

But this is no confabulated or rationalized cover of Blind Blake Higgs’s or Harry Belafonte’s versions. This is indeed the work of ‘Cash, the Integrator’, and that’s about more than adding Memphis to the song’s internal geography. Much has been made of his take on this ballad for his American Recordings. I can add little, though I’ll try. Let’s hear it first.

Lyrics for “Delia’s Gone” by Johnny Cash – 1994 version

“Delia’s Gone” live concert video “Delia’s Gone” Music video w/ Kate Moss

Some of you folks may not know that Cash waxed the song much earlier, in 1962, with a different set of lyrics. There is a short version and a longer version with even more lyric fancy, presumably from the early 1960’s as well. While neither come close to having the power of his 1994 track, he does make the key change that would allow his final work with the ballad to reach such heights. He puts it in the first person. Johnny inhabits the killer’s skin. The way this affects the listener can’t be underestimated.

I didn’t cover it in Part 1, so we need to include those versions here.

“Delia’s Gone” by Johnny Cash – 1962 version (Spotify) (YouTube)

Lyrics for “Delia’s Gone” by Johnny Cash – 1962 version

“Delia’s Gone” by Johnny Cash – Longer 60’s version (Spotify) (YouTube)

Lyrics for “Delia’s Gone” by Johnny Cash – Longer 60’s version

Finally, there is yet another version from Cash’s TV show, in 1969. The way he smiles when he sings of shooting her is a perfect visual counterpoint to what one sees in the music video with Kate Moss linked above. He is clearly playing the killer in both. But if you compare them, I think you’ll start to see that he interprets the character he inhabits in both differently. Truly, both are ostensibly remorseless. But in all of the 1960’s version, the traditional ‘jolly’ killer is still there – and singing about such a murder is something of a joke. Indeed, Cash calls it “a love song” with tongue in cheek on TV.

But people and songs both change. Simply put, his 1994 take is a mature realization and evocation of the ‘beast inside’. Cash, as much as anyone, helps us look at this old song (and, really, the murder ballad tradition itself) in a new way. Only, he’s not looking back as a scholar or an observer; he was a participant throughout. It’s hard to imagine a more honest reflection.

Now, I could write for hours on what I think Cash did, but nothing I said could approach the eloquence and soul of poet Tony Tost‘s chapter on the song in his book for the 33 1/3 Series on Cash’s American Recordings. If you’re looking for what a seer of myths might divine in Cash’s “Delia”, you must go there. It is sublime writing; though Tost will, in turn and rightfully so, point you back to the music for what you most ardently seek.

“American Recordings brought Cash back to the public as the lone survivor of a lost republic, the final rememberer of how—for good and for ill—things shall never be again. He was an archaeologist of twilight, the grievous scholar of American sin. Listening to the record, it is like overhearing history singing to itself.”

“Final rememberer” – it’s a powerful phrase, and appropriate. I think, though, with “Delia’s Gone”, Cash does more than remember things that never will be again. By playing the character as he does, he shows us a way to know ourselves through this song that had never been a part of “Delia’s” way before. Oh, of course there’s nothing new about using art to peer deeply in to the dark recesses of human nature. But, in my listening I can’t find “Delia” as a song to be such a lens until Cash ground and polished it in 1994.

Again though, more on that when we close. Unless you want to just skip ahead past the next section and get right to it! Have at it if you will.

Otherwise, let’s next see where Delia traveled after Dylan and Cash set her on a new path in the 21st century.

Delia – Her Second Century (so far)

What I’ve got for you in this section is admittedly incomplete. It’s not because I can’t find all of the recordings of “Delia” cut after 1994. You can find most of them mixed throughout my Spotify playlist. There are a few others on our YouTube playlist. It’s just that I find some of it boring and derivative. This hits interpreters of Cash the hardest below. Standing on the shoulder of that giant is an easy way to fall unless you truly have the reach to get to another level. I find few of the many covers of his take that interest me, much less inspire me. So, I apologize that my curatorial license will keep all but two of them out of this post.

“Delia’s Gone” – by Eric Bibb (Spotify)

I hope what I do include though is to your liking.

Eric Bibb – 2001 – This one reaches back to the older Bahamian versions, though the playing and tone are very much unique and quite lovely to boot. Bibb is a master and a proper inheritor of our diverse folk music tradition, and he will remain an excellent post-modern interpreter of that tradition for years to come if we’re lucky.

Kyrt Gates – 2005 – This is one exception to what I said above. Though a straight cover of Cash’s version, Gates turns it into an indie/grunge anthem. While it’s not exactly something I’d listen to over and over, it does represent a somewhat fresh take on Cash that’s worth a spin on your virtual turntable.

“Delia’s Gone” – by Kyrt Gates (Spotify)

Delia (Scott Greene, Gwen Tracy, and John Krips) – 2006 – It’s probably not slipped by you that women don’t usually sing this song. We’ll see a major exception to that below, but this one comes earlier. A woman’s voice in the lead just changes this song. There is, as well, the addition of a new opening and closing verse which references the true story, and so makes this take more about Delia than her killer.

“Delia’s Gone” – by Delia (Spotify)

Hat Fitz and Cara Robinson – 2010 – I’ll admit that this take is not significantly different than others inspired by Gary Davis or his students like Grossman, Bookbinder, and Bromberg. The changes are subtle. There are some slight lyric embellishments, especially in the refrain. The finger-picking feels traditional but has a certain innovative quality. There is a woman’s voice, though not in the lead. And there’s a bit of flute. All of these small elements combine to make a version I feel is different enough to be worth a listen, and sweet enough to be worth another.

Hat Fitz and Cara Robinson – 2010 – I’ll admit that this take is not significantly different than others inspired by Gary Davis or his students like Grossman, Bookbinder, and Bromberg. The changes are subtle. There are some slight lyric embellishments, especially in the refrain. The finger-picking feels traditional but has a certain innovative quality. There is a woman’s voice, though not in the lead. And there’s a bit of flute. All of these small elements combine to make a version I feel is different enough to be worth a listen, and sweet enough to be worth another.

“Deliah” by Hat Fitz and Cara Robinson (Spotify)

Pat Conte – 2011 – I don’t know much about Pat Conte, yet. But if the quality of the music I’ve found on his album American Songs with Fiddle and Banjo is any indication, this won’t be the last time he shows up in our blog. He’ll certainly be making repeated aural appearances in the various speakers around my house. He does something here similar to what Dylan did, only this time it’s a powerful mix of Bahamian and American lyrics with traditional banjo playing and singing. This particular fusion of island and mainland is unique in my listening experience for “Delia”.

“Delia’s Gone” by Pat Conte (Spotify)

Ruth Gerson – 2011 – This is the other exception to my boycott of Cash covers after 1994. And this is one to which I’ve listened repeatedly. Gerson’s take is unique, as is her approach to her entire 2011 album Deceived. It is a work full of violence and death, aimed on a practical level at raising money for fighting various forms of domestic violence. Her art though is even more ambitious. It is aimed at raising consciousness about our ability to “annihilate.” I’ll get to that in a second. First, listen.

Delia’s Gone – One more round… “The beast in me is caged by frail and fragile bars.”

It’s Gerson who brings us to more than a musical close today. Her work on Deceived is a fine jumping off point to talk about that beast.

In 2011, Gerson gave an interview to Ann Powers for NPR that they published as “The Allure of the Murder Ballad.” I know I keep sending you off to other sources, but reading that interview will enrich you. As well, it will save me having to quote her ten different times below.

You see, we’ve just started our third year of writing about murder ballads here; our third year of charting in detail for ourselves the coastline of this expansive piece of ‘old, weird America.’ And for all that time I haven’t, at least for myself, been able to sail far enough up the many outlets we’ve found to know too much about the depths of this land. It’s a strange thing to say for having spent so much time on this water, but it’s true.

But that’s finally starting to change for me, at least with regards to the traditional murder ballads. I’m coming to understand that my fascination with them has much more to do with who *I am* than with who the anonymous writers and early singers of those bloody songs were. That’s not as simplistic as it sounds. We are fooled, I think, by the universality of violence, of killer and victim, into believing that somehow these songs persist in our collective memory because they must mean something like the same thing to us as they did to the people who created and first sang them. I am starting to believe that, mostly, it just ain’t so.

Ruth Gerson – 2014 – from her website

Consider. Traditional murder ballads told the ‘crime news’ of the day. They gave a sense of justice, of rectitude, where law was otherwise powerless or meaningless. We’ve got courts and police forces that are expansive, and cable news to tell us about it all 24/7. Traditional murder ballads gave warnings to young people about evil, or what today we’d call aberrant behavior. We have public school health classes, counselors, and psychologists. Murder ballads provided bloody entertainment. We’ve got cop and court shows galore, and video games, all full of the most grisly fantasized murders. And yet, though we clearly don’t need them for much of what they did for our forefathers and mothers, we still sing murder ballads and pay money to hear others do as well.

Well, some of us do. Today, some look at Cash’s “Delia’s Gone” and other murder ballads with revulsion. That’s not hard to understand. On the surface, his song appears as misogyny. In fact, one can make an airtight case that some traditional murder ballads ‘work’ in part because of deep-seated misogyny. But – and here’s the point – Cash’s 1994 recasting of “Delia’s Gone” is no longer traditional murder balladry. It’s a murder ballad for post-modern ears. A ‘sub-mo-chine’ wouldn’t work for Matty Groves or Lord Thomas. And all Stagolee needed was a blue steel .44 and a Stetson hat. There’s something else going on with this one.

Now, Dylan recorded “Delia” the old way, and of course there is still an important place for that. But only in the old way do we see “rectitude” in this song.

As Gerson pointed out, “It feels more devastating, when you consider the history of the song, that the murderer may be so young and the victim is a child. Children are capable of the same violence adults are capable of. When it is a small child, in general, they do a lot less damage, but I have seen first-hand 15-year-olds who are capable of an enormous amount of damage.”

As we saw last week, the fact that “Delia” is a story of teenage murder is excised from *every* of the many traditional versions of the ballad. Why? Well, consider. Instead, Delia is a rounder and a gambler, or a whore. Or she lies about being willing to marry. Or she cusses out her man, wickedly, in public. Now, I think Dylan meant something deeper about both killer and victim when he said that “Delia” has “rectitude.” But one way or another, it was easy in the old way of hearing it for a listener to say ‘well, Delia had it coming.’

Today, many folks just don’t see things that way. As William Munny said in Unforgiven, “We all have it coming, kid“. Cash in 1994 made it impossible for me to find righteousness in this murder ballad. He tried to put it in there in the 1960’s, but it just doesn’t work for me with his creative first person approach – “durn her mangy hide.” No, that doesn’t make me smile; though not because of some sort of moral superiority on my part. I’m just looking for something else in these songs. Maybe you are too. I think Cash understood such things by the 1990’s, and I think that’s part of why his American Recordings is so powerful. I don’t see righteousness in it, but I see humanity. Those folks who see nothing but misogyny in “Delia’s Gone” are missing the ancient actor’s mask that Cash wears – or, to put it another way, the mirror he holds up. Gerson, though, sees it and picks it up herself.

“Speaking for myself, the allure of the music has to do with a desire to understand why, when we come face-to-face with another, we can annihilate. I can understand an impulse to want to, but I cannot understand where, once met with the face of another who holds no threat to me and could not defend herself, I would get the ability to do what’s done in these songs. I have grappled with and studied violence since I was in high school. I sing about it because I want to talk about it. Trying to understand it is part of who I am…

In the songs of Deceived — in every one — I am someone else. I am holding up pictures, I am holding up mirrors.”

It’s true that the majority of traditional murder ballads feature male killers and female victims. There can be no doubt that misogyny is part of the equation. But in those ballads we also see fratricide, sororicide, matricide, patricide, infanticide, suicide, and the full range of accompanying horrific behaviors, done by both genders. And on those cable news shows today we see pretty much the same. A mother kills her little daughter, tells lie after lie, parties it up when she should be weeping, and still manages to win an aquittal? Did you ever hear “Two Babes“?

There is nothing new about human violence or depravity. To see murder ballads, then or now, as only propelled by misogyny I think misses glimpsing an even wilder beast.

Coda – The Beast in Me

I cultivate compassion in my life and, though I stumble and fall regularly into negativity about individuals, I don’t *hate* people. I’m capable of being blind to all sorts of ‘isms’, though I try to see them; but I certainly don’t *hate* women or any group of human beings. I imagine you’re pretty much the same. And we both love murder ballads.

I don’t even kill bugs unless I have to. You may have a slightly different tolerance for triggering the application of lethal force, but I’m sure it falls *well* short of any form of homicide. And we both love murder ballads.

No, we’re not monsters, you and I. But we both know that the beast of whom Johnny Cash sang is still inside us. Could it be that it might be caged by being given free range in art? Can gentle people achieve non-violence by roaming that open field?

Could a murder ballad help a human being to realize something of peace? Gerson might think so.

“Murder is not a crime that can be paid for. There’s retribution and punishment, but there’s no restoration…

I think the whole world pays for the murder of every face. That’s why it makes sense to talk about it and why we all have a responsibility in working towards understanding it, with an ultimate goal of living in peace.”

Is that what Delia tells us now? I don’t know.

But, since I was a child and as long as I can remember, I’ve loved looking into mirrors.

Thanks for reading and listening this week, folks!