|

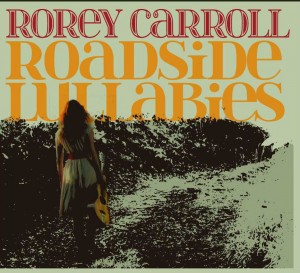

| Rorey Carroll |

“…it’s such a powerful thing to take someone’s life. It’s one of the most powerful things, and it’s something that anyone could do. I think people are fascinated with death and murder for the fascination with their own darkness.”

Part One of Murder Ballad Monday’s interview with Rorey Carroll.

Rorey Carroll: It seems like the murder ballad—it’s not exactly an old, lost art, but it’s a rare gem when I see a new murder ballad that’s written in this day and age. When I moved to North Carolina, I heard a lot of them. I’m friends with a lot of traditional bluegrass musicians. I hire a lot of them for the band.

A lot of the murder ballads are simply violent—shoot a girl in the head, and shove her in the river because he loves her so much. I was fascinated by that, but it wasn’t something I was subjected to until I moved to North Carolina. I immersed myself into them for a while. So, that’s why I knew I had to write one. Just a kind of initiation, I suppose.

Murder Ballad Monday: When did you to write “Head Hung”?

RC: I wrote “Head Hung” when I was living in my car, in a skate park in Asheville, NC; and I had been hearing these murder ballads, and I knew I had to write one from a woman’s perspective. I found myself with a bottle of whiskey, and pretty much wrote it in the front seat of my car.

MBM: It probably didn’t feel like the safest time of life for you.

RC: It was definitely a time when I was figuring out my place in that town. I had a lot of anger in my life, a lot of passion. The amount of talent in that town—very raw talent, very emotional, very distinct—definitely pushed me. The people around me pushed me, and vice versa.

|

| Photos by S. Bigger |

But, at the time I wrote “Head Hung,” I was having a hard time figuring out what I wanted to do. I didn’t really have a place to start, so I decided I would just live in my car until something found me, and then it did.

MBM: Was the song developed as an intentional part of your album, Roadside Lullabies,or was it a stand-alone piece?

MBM: Was the song developed as an intentional part of your album, Roadside Lullabies,or was it a stand-alone piece?

RC: My album was recorded mostly from a bluegrass standpoint. I knew I wanted bluegrass instrumentation. I wanted songs on it that would mix well with that instrumentation, but “Head Hung” was not written for the album. It was just a piece that just came out of my head. It was a labor of love. I wrote most of it in one sitting, but I definitely went back to it and edited a bunch.

MBM: “Head Hung” doesn’t seem like a self-defense kind of murder ballad to me, or at least simply so.

RC: A lot of women struggle with the feeling of being either looked over or looked upon by a lot of men, and by society in a lot of ways, and this was kind of my lashing out against that.

It was more so just a woman fed up with men, basically, for lack of a better way to explain it. It’s almost a song in response to all the murder ballads about men killing women because they supposedly love them so much. Most of them seem to come to that.

|

“Little Water Song,” by Anguarius

See our discussion of the song “Little

Water Song” here. |

MBM: Is it more about rage than self-defense?

RC: I think that I was going more for self-defense, but I see that there’s an ambiguity to it. What I see is that this woman was going to become a rape victim. She was tired, she was working, she was drinking, and she just didn’t want to be hassled.

I was living in my car, and I was on the street, and there are a lot of street people in Asheville; so the song was a natural thought for me in that context.

MBM: “Head Hung” is in the minority of murder ballads in that it represents a female protagonist killing a male antagonist. The tradition is often linked to misogyny. Do you think that’s justified?

RC: That’s the way I thought of them when I first started hearing these songs. I thought, “Well, what did she [the victim] do?” This is why I really wanted to write a murder ballad from a woman’s perspective. It comes from a place of the emotion of love coming on so strong, and then the hatred coming from that love—the sense of shock at that love not being reciprocated.

|

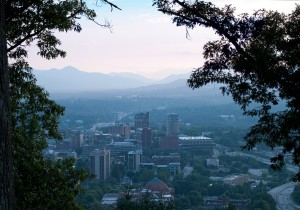

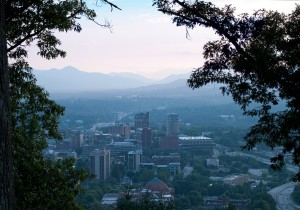

| Asheville, NC |

MBM: You mentioned that you wrote this song in Asheville, NC.

RC: Asheville definitely has a level of that Southern darkness—that kind of dark, deep secret about it. It is more liberal and crazy than most of the South, but it still has an underlying southern mystery.

I was living in Leadville, CO before I decided to hike the Appalachian Trail. I had never been to the South before. As soon as I started hiking the trail, I fell madly in love with the Appalachian Mountains. Something about those mountains definitely grabbed me. You could feel when you left the South when you were hiking on the trail. When I finished the trail, I knew that’s where I wanted to be. I worked as a wilderness therapy guide for two years after hiking it, and then I moved back to the South.

MBM: What’s interesting to me is that there seem to be no, or relatively few, murder ballads in Northern Appalachia.

RC: I think there’s just a lot of mystery to the South, the Southeast. It has a past of being a sunny dark place. It has a looming, woodsy, dark feel, with a lot of mystery, and a lot of hidden things. A lot of it has to do with the physicality, and a lot of it has to do with the mentality of the people in the area—and the environment. Some environments are harsher than others, like the Desert Southwest. In the Appalachian mountains it’s not the case. It’s a very forgiving place, but still has these mysteries, these hidden things, and these songs.

MBM: Have you ever adapted “Head Hung” to reverse the genders of the main characters? What happens to the song for you when you do that?

RC: It would be a completely different song. It would turn it from a semi-self-defense/semi-rage song to a brutal murder song. It almost seems woman driven. The song comes from a very female place; like an inner female rage. I couldn’t imagine putting things the opposite way.

It’s such an emotional thing to write a murder ballad. You really have to put yourself in a place where you’re actually murdering someone. For any kind of writing, you have to do the same. You have to be in the mindset where you are that killer just for a minute, at least. Trying to fake it is a very difficult thing, and it’s very obvious when you do.

The hardest part is when you are actually killing the person. It took me a long while to be able to do that. And even thinking about that happening…it’s really interesting…

MBM: Is there any remorse or repentance in the song?

RC: Yeah, there is—at the end. The line that has that is “and I felt the earth below me, as my soul went away from me.” Also when she’s looking at “what her dirty hands had done.”

A woman’s sexuality is sacred, a powerful force, a sort of entity, and when I was coming into my own with it, I realized how society seems to try to captivate it, enslave it, or overrule it. Especially in Christianity, which is where the line: “he said girl, the devil lies in you. Won’t you come around the corner let daddy make a good girl out of you.” It was almost like I wanted to kill off that which I was struggling with, but in the end it is something I needed, religion (some sort of spiritual refuge). Sort of brings it full circle to the tradition of the murder ballad, killing off the thing you need to come to terms with.

MBM: Given the emotional or psychological places you have to go to for “Head Hung,” do you have another song that feels like a refuge to you from that place?

RC: On my normal set list, I usually ask people if they want to hear a love song or a murder ballad, and they always respond, “Murder ballad!”

MBM: Why do you think that is?

MBM: Why do you think that is?

RC: I think people are fascinated with that dark side of the human soul, of the mind. At least for me, that’s why I’m drawn to murder ballads, horror movies, and horror comics. It’s a natural fascination. It’s such a mystery. The mind is such a mystery and death is such a mystery, and it’s such a powerful thing to take someone’s life. It’s one of the most powerful things, and it’s something that anyone could do. I think people are fascinated with death and murder for the fascination with their own darkness.

But, when the audience calls for it, I always do a murder ballad, and then I’ll either play something lighter next or go further in and do another dark song, but I’ll always come around to something lighter.

I have a fan who told me that “Head Hung” is like medicine. You can only take it in little pieces, but when you do, it’s healing.

MBM: Can you tell me about some of your other favorite murder ballads?

RC: When I think about it, I don’t really know a lot of them. My friend Amanda Platt—she’s in a band called The Honeycutters, which is one of my favorite bands—has written one of them. It’s a song called “The Ballad of Lucy Bady,” and it’s a song about a father killing his daughter because she’s so beautiful. It’s one of my favorite songs. It’s so dark. It’s so descriptive and beautiful. Listen to “The Ballad of Lucy Bady” here.

|

| The Honeycutters |

It seems like a lot of the murder ballads that are written today, and this might be because I hang out with a lot of acoustic musicians, have an old feel to them—almost like an old novel. I think this is because you sometimes have to put yourself in that kind of place, to give yourself that kind of distance, to go through with writing it. “Head Hung” is not really that kind of old style. It’s not removed. When I was writing, I did have to come up with a way to separate myself from it, even though I did write it in the first person.

It’s now kind of funny… I shouldn’t say it that way… It’s now mildly entertaining to me when I perform it, because some people are shaken up by it. It’s more entertaining now because I’m more like the messenger than the message. I’m doing it as performance.

I don’t like to do that song around kids. I know when I was a kid, I was fascinated by horror movies and horror comics, and I’ve had parents tell me it’s not that big of a deal, but it’s more of a personal issue. A lot of kids don’t pay attention to the words, and just enjoy the music.

My dad is a guitar player. I love his guitar playing. He never pursued it professionally. All the songs he sang when I was a kid, they stick with me more than any other songs.

But there was one time at a festival, probably about a month after I wrote it… There was one girl who was staring at me, like she was listening to every word I was saying, and I had this sense of guilt in the act of singing about murder.

I was at an outdoor music festival. Here’s this beautiful setting, and I’m singing this dark song, and this little girl was staring. She was front row, and I’ll always remember that feeling, like that little girl actually heard that song. I never wanted to play it in front of a child again. But then I talked to the mother afterwards, and she was ok with it, but I still felt a sense of guilt.

Next up:

In the next post, we’ll continue our interview with Rorey Carroll–as she reflects on the experience of loss and how her experience as an artist and performer is forever altered in its wake.

MBM: Was the song developed as an intentional part of your album, Roadside Lullabies,or was it a stand-alone piece?

MBM: Was the song developed as an intentional part of your album, Roadside Lullabies,or was it a stand-alone piece?