“Won’t You Come and Sing for Me?” – CwD 9

Hazel Dickens (1936-2011)

“I feel the shadows now upon me…”

I remember driving to Mt. Greylock with Pat one time, telling him about a singer I had just discovered. I said she had the kind of voice I’d like to hear on my deathbed. This meant something to me more than just that her voice was beautiful. I was hearing beauty, truth, and love in that singing; hearing something resembling the sacred coming through it. I was probably also connecting with the comfort of being sung to, which doubtless invokes experiences so early that they have faded from conscious memory. Pat, unsurprisingly, called me out as a weirdo.

I’ve had this feeling about a few singers–some because of the quality of their voices, others because of my relationship to them. It doesn’t strike me as especially morbid or morose. I don’t spend a lot of time envisioning this kind of musical tableau. I harbor no illusions that it’s a gig anybody would want to play. It could, however, give a whole new meaning to the idea of the “Ultimate” playlist. The feeling about these voices draws from how I feel about music generally, and most especially singing. Music provides a glimpse, or an avatar, of the transcendent. It also voices joy and hope in the face of all else.

If my virtual choir of “deathbed singers” is bizarre, perhaps I have this blog to thank for it. Today’s song also bears some responsibility. Hazel Dickens’s “Won’t You Come and Sing for Me?” involves this very idea. We’ll discuss it, in that light, as part of our “Conversations with Death” series.

“Won’t You Come and Sing for Me?” reflects on mortality without murder. The song also presents a “Conversation with Music,” or perhaps a “Conversation with Memory.” They are somehow all the same conversation. This song provides a bluegrass analog to Merle Haggard’s “Sing Me Back Home.” Haggard’s song tells in two verses of a condemned man’s wish for comfort in the songs of his childhood. “WYC’s” protagonist faces a natural death recalling cherished memories spent with fellow churchgoers, inviting their sung benediction in the final days.

Lyrics (These are the lyrics from Dickens’s memoir. Various artists have tweaked them, including Hazel & Alice above. This track and most of the rest in this post can be found in the playlist below.)

Qui cantat, bis orat

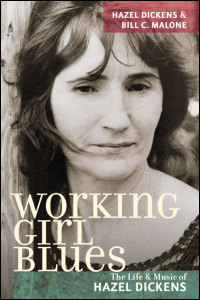

Dickens discusses the song’s inspiration in her music memoir, Working Girl Blues:

“I’m really not religious, to tell the truth. However, when I was growing up, I was impressed by the love and kindness that was openly shared and displayed among the brothers and sisters of the old Primitive Baptist church. It was that and the singing of the old songs that stayed in my memories down through the years (not the preaching). Particularly at the end of the service after they sang the parting song, they go around and shake hands and greet each other, humbling themselves before each other with smiles and hugs and invitations to go home with them and share a meal. This kind of humility and harmonious spirit of a common people inspired me to write this song as a tribute to that place and time tucked away in the corner of my memory.”

In his brief biography of Dickens in Working Girl Blues, Bill C. Malone writes that “Primitive Baptists exclude musical instruments from their church services. They believe that the human voice is the only instrument required for the worship of God.” Their hymn lyrics emphasize “the evanescence of life, the certainty of death, and the promise of heavenly reward.” Dickens’s song is not much more explicitly Baptist or Christian than that. “Beyond that dark river” is a metaphor that feels drawn from another, distinct cultural well.

Primitive Baptists in rural West Virginia may seem far distant from the Latin epigraph above, which reads, in essence, “the person who sings, prays twice.” The epigraph is part of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. It is a rough condensation of a longer statement by St. Augustine (see below). The sentiment in common between them, though, involves the affirmation that singing involves both mind and body in prayer. Singing enacts our vitality, even when invoking our mortality.

Primitive Baptists in rural West Virginia may seem far distant from the Latin epigraph above, which reads, in essence, “the person who sings, prays twice.” The epigraph is part of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. It is a rough condensation of a longer statement by St. Augustine (see below). The sentiment in common between them, though, involves the affirmation that singing involves both mind and body in prayer. Singing enacts our vitality, even when invoking our mortality.

Dickens said “If there’s any religion in my life; it’s for the working class.” Her appreciation in this song focuses on the warmth and fellowship of common people, and the songs that bind them together. I started from a different tradition than Primitive Baptist, and I’ve followed different path than Dickens as an adult. I resonate, though, with her feeling that it’s the music, not the preaching, that stays with you. Without music, it’s a challenge to make the rest of it work. Even if Dickens didn’t feel she was a religious person when writing the song, she captures something authentic about music’s role for many religious people and many religious communities.