War & Love: Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town

“Those songs are gifts”

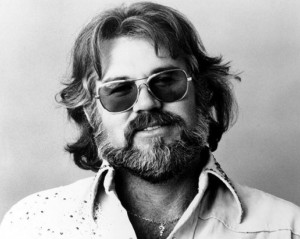

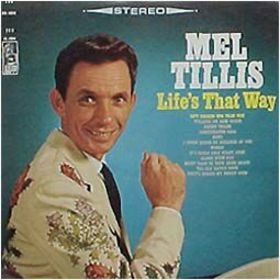

On warm, humid evenings in Pahokee, Florida in 1947, teenager Mel Tillis would hear the neighbors arguing. Through open windows, broadcasting across the space between their home and his, their recurring shouting match of distrust and acrimony would resume. The belligerents were a wounded veteran of the Second World War, and his English war bride, Ruby, a nurse who had helped bring him back to health before he brought her back to Florida. His recovery was not complete, though. His wounds would tie him to the house. Ruby was not so confined, however, and their fights would erupt over her husband’s suspicions about why she was going out.

Tillis turned to his mother to understand what was going on. “’Mama, what’s happening over there?’” Tillis later recounted, “and she’d say, ‘He’s just a mean old thing. He’s accusing that Ruby of everything in the world. She’s a NICE girl!’.”

Almost twenty years later, Tillis was stuck in traffic, listening to a song about another mother-son dialogue: Johnny Cash’s “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town” (YouTube, Spotify).

“I was coming home from the office – I say the office, it was Cedarwood Publishing Company. I was assigned to write for them. I had a little office there. And I was coming home and got I stuck in the traffic. And I had the radio on. And Johnny Cash came on (Mel starts singing in a Johnny Cash voice) “Don’t take your guns to town, son, Leave your guns at home boy.” And I just sang (Mel starts singing in his voice) ‘Ruby, Don’t take your love to town.’ It reminded me of a situation that happened in Florida. And before I got home, I had that song written.”

When he got home, Tillis played the song for his wife, who declared it “the most morbid song I’ve ever heard.” He knew he had a song, though. In an interview with Tillis much later, Larry Wayne Clark said “that song has got to be as bleak a hit song as I’ve ever heard in my life. It’s uncompromising.” To which Tillis replied, “Yeah. Those songs are gifts.”

Tillis recorded a demo, and took the song on the road to Europe. “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town” caught the attention of a few country artists. Waylon Jennings recorded it (YouTube), but Johnny Darrell was the first to release it as a single (YouTube), in February 1967, reaching #9 on the Billboard Country charts the next month. Such country music stalwarts as Roger Miller (YouTube) and George Jones (YouTube) also recorded the song.

Porter Wagoner invited Tillis to appear on his variety show in 1967 to perform “Ruby,” commenting at the end that the song was special for being based on a true story.

“Ruby” might have remained a minor country hit, and not an international blockbuster, had it not been for two forces converging in the summer of 1969: a ’60s pop band in a hurry, and an upwelling of protest against the Vietnam War. A performance by this pop band first drew me into the song, and I wanted to understand what made that performance so compelling, musically and lyrically. In the process, I uncovered a song that spoke to the “anxieties of the age” in some surprising ways, and still does. That is the story that’s ahead, and it’s a signal case of the ways these songs can reflect back the most basic human feelings as well as some cultural forces and metaphors that are well worth our scrutiny.