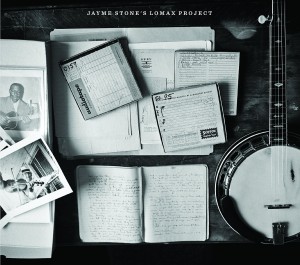

JAYME STONE’S Lomax Project

JAYME STONE and friends

Jayme Stone’s Lomax Project

Borealis 235

There is a recording of John Hartford in the studio giving direction to the musicians he’s gathered there. Whatever the song they were prepping – it may have been “Madison Tennessee” – he says, “this is not going to be a showstopper. I want to do this like it was ‘Brushy Fork of John’s Creek.’ I want it to be straight ahead, where it leads us to the music, and not tricky.” It’s an idea that was central to Hartford’s career, or at least the later part of it; his performances relied entirely on the content, and his arrangements were careful ones, build to support the content, to lead us to the music. He felt that it wasn’t his job to promote the music so much as to hold it up, to turn it around, and to show it to us.

Jayme Stone is cut from the same musical cloth. He’s accomplished enough as a musician to stop a show, and to be tricky, but what makes his work so effective is that he doesn’t. Like Hartford, he trusts the content, is obviously excited by it and wants to share his excitement with us. Like a child bringing a grasshopper in from the yard saying, “Look at this!” He’s not interested in building a better grasshopper, rather he wants to bring the grasshopper to us so that we can see how cool it really is.

His latest release, the sprawling Lomax Project, is an excellent example of that impulse. Over the course of 19 tracks he pays tribute to song collector and musicologist Alan Lomax, who would have been 100 this year. Lomax has had more influence on folk and roots music than most of us know, and then some. Stone has gathered a fantastic group of musicians to survey all the corners of the musical world that, at one time or another, attracted Lomax’s attention, from the hollows of Appalachia to the Caribbean.

There are lots of very familiar songs here, though Stone writes that “the unexpected chemistry of collaboration [makes] music that’s informed by tradition but not bound to it.” It’s a fine balance, and you need to give yourself over to it a bit. Some songs, such as “Shenandoah” and “Goodbye Old Paint,” are so familiar that any adjustments can feel artificial or forced.

But, even if some things might work a bit better than others, it’s true that everything on this disc is interesting, and everything benefits from repeated listening. It doesn’t hurt that Stone collaborating with some of the best, including Tim O’Brien, Bruce Molsky, Julian Lage, Margaret Glaspy and Brittany Haas. Molsky’s “Julie and Joe” is gorgeous, marrying two traditional tunes, “Julie Ann Johnson” and “Old Joe Clark,” the second done here in a minor key rather than the typical major, and drawing on a Cajun style of fiddling. It’s one of those tracks that you get stuck on, playing again and again.

Stone’s role, perhaps more than anything, is as a kind of musical director, bringing together the kinds of musicians that share a vision of traditional music as alive, important, and beautiful, and with the kind of chops needed to show all of that to us. The variety of songs is wonderful, and the program includes an a capella call and response work song, “Sheep, Sheep don’t you Know the Road,” and a calypso piece, “Bury Boula for Me” featuring Drew Gonsalves. There’s a charming song, “T-I-M-O-T-H-Y” that apparently was collected by Lomax in the Dutch Antilles. It features Tim O’Brien and Moira Smiley. Did I say it was charming? When you listen to it, you’ll see what I mean.

There is a lot on this recording, and there is a lot in the package, too … including two essays as well notes on each of the songs. All of it is absolutely welcome. Stone is the leader, but this isn’t a “banjo album.” Rather, it’s an album of beautiful, intriguing, thoughtful music coming from a collaboration of outstanding musicians who apply their talents together.

It was a big project to undertake, perhaps, and of a kind that we see less and less of these days. It’s an album with a beginning, a middle, and an end … asking us, as listeners, to immerse ourselves in the idea of it all. It rewards that attention as much as it captures it, leading us to the music, rather than pushing us to it … something we may not be so familiar with these days: give and take.

— Glen Herbert