Cut down a man in cold blood…

“None recover, they are just replaced.” – Robert Hunter, 1995

Note: This is Part 3 of a three part series. See also Part 1 and Part 2.

Introduction

At the free concert at Altamont Speedway on December 6, 1969, an eighteen year old man pulled a gun in a scuffle with a member of the Hell’s Angels; the Angels then stabbed and beat Meredith Hunter to death. Over the course of the event, and unrelated to the deadly brawl, three other people died accidentally. Four babies were born.

Those of us who sing and listen to murder ballads know that we humans – when at a safe distance – have the capacity take horrible events at face value, to neither attach nor detach ourselves emotionally. We can thus look at our humanity as in a mirror; and in that reflection, our natural capacity for compassion shines.

But journalists and critics wrote the story of Altamont with less balance. Paradox, messy facts and infinite shades of gray cluttered the narrative and made it hard to find intellectual *meaning* in the random brutality. So, the story eventually got skinny; Altamont ‘meant’ the end of the counterculture, the loss of hippie innocence. If Woodstock got a generation ‘back to the Garden’, Altamont sent them packing east of Eden. The canned textbooks in my school to this day tell one version or another of that tale.

There is truth in that perspective: though it is, at best, greatly oversimplified. But I’m not interested here in parsing the history, factual or otherwise. There are other ways to make meaning. There is music after all.

In the heat of the sun a man died of cold…

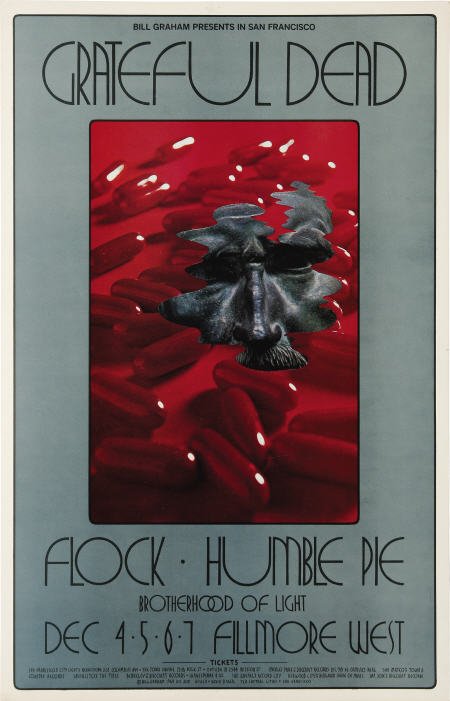

The Grateful Dead refused to play at Altamont because the scene got so ugly. They were, quite simply, afraid. The next night, they played The Fillmore and opened with “Black Peter”, their heaviest song about death to that point. They’d introduced it into their repertoire only three nights before. Though not a murder ballad, it was apt.

Black Peter (studio version, Spotify) Lyrics

In one of the annotations on David Dodd’s lyrics site, Jurgen Fauth makes an interesting comment. “There is also an idiom in German, “jemandem den schwarzen Peter zuschieben.” Directly translated, it means to “slip someone the Black Peter”– to put the blame on them, to frame them, to put the ball in their court: if they keep it, they lose.” The metaphor comes from a card game of the same name. (And again we see that theme of chance?)

If you read the columns penned by Ralph Gleason in the immediate aftermath of Altamont, particularly the one titled “Who’s Responsible for the Murder?” you can see that he (and no doubt others) started trying to ‘slip the the Black Peter’ to the Dead.

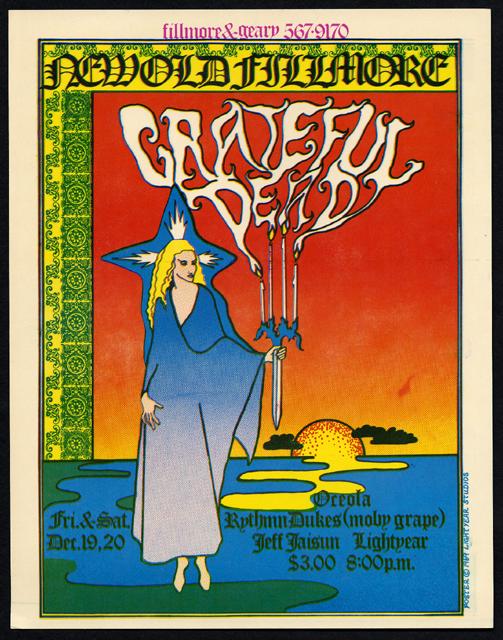

It didn’t take long for them to offer a response. Two weeks after Altamont, at The Fillmore on the 20th, the Grateful Dead debuted “New Speedway Boogie”, a Hunter/Garcia collaboration. Hunter states of this song in his book of collected lyrics simply “Written as a reply to an indictment of the Altamont affair by pioneer rock critic Ralph J. Gleason.”

New Speedway Boogie (studio version – Spotify) Lyrics

“New Speedway Boogie” is not a defense, exactly. It eschews blame and takes the long view. It neither dismisses Meredith Hunter’s murder nor wrings hands over it. In that sense at least, “New Speedway” is like some of the murder ballads we’ve considered. It looks at the violence of Altamont honestly and seriously, but it is interrogative in a way quite different from Gleason’s articles. It assumes that the counterculture’s social experiment is still the best “highway to ride.” So the question is not “Who’s responsible?” but “What do we do now?”

All he said: When I’m dead and gone, don’t you weep for me…

“New Speedway Boogie” was not the Dead’s only attempt to find meaning in Altamont through their art. The night before they debuted “New Speedway”, they let loose a song called “Mason’s Children”. Hunter also made a note on this one in his collected lyrics. “An unrecorded GD song dealing obliquely with Altamont.” The song has obvious power, but is somewhat inaccessible, even when one knows the inspiration.

Mason’s Children – 1/24/70 Honolulu (Spotify)

I include it here not simply because it gives us another angle from which to consider the Dead’s creative response to Altamont. There is also a possible connection to our topic song of the week, “Jack Straw.” One of the lines from “Mason’s Children” ends up in another form on Hunter’s manuscript of “Jack Straw”, though it didn’t make it in to the final version. It’s about paying back a debt. I’m not sure of the connection, but it’s interesting that the concept of a debt to be paid is a thread between both. I’d love to ask Robert Hunter about it.

Cut down a man in cold blood… might as well be me…

Oh yeah! That’s how we started this week, didn’t we? “Jack Straw”!

We’ve also explored this week the connection between “Jack Straw” and Of Mice and Men, which Bob Weir revealed as partial inspiration for the song. I tried to prove in that post that, though inspired by Steinbeck’s work, “Jack Straw” is in no way a retelling of the story. So what is it then; a purely fictional tale of murder that they just happened to write a year after Altamont?

We’ve seen above that within two weeks of the event, the Dead wrote and began performing two songs inspired by Altamont and the reaction to it. Neither lasted very long in the Dead’s repertoire however. “Mason’s Children” was performed fifteen times and was retired before the spring of 1970. “New Speedway Boogie” lasted a bit longer, into the fall of 1970, and reappeared again only in early 1991!

Did the Grateful Dead simply lose interest in using their music to evoke meaning around their experience of Altamont and its aftermath? Perhaps. But all I’ve read and know about the band suggests that they didn’t stop dealing with what happened; quite the opposite in fact. Why would they abandon music as a way to put it all in context? I suspect that those two songs just didn’t dig deep enough, that they just didn’t truly get to the heart of the matter.

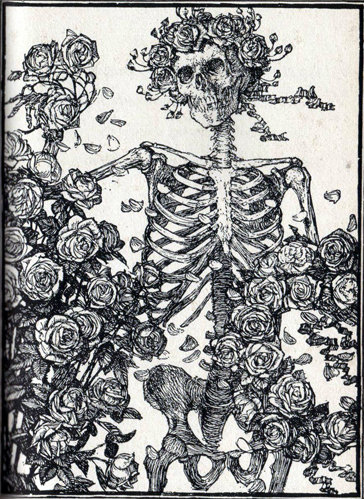

“Jack Straw” on the other hand is a different sort of song. There is nothing of rhetoric or topical context there. It’s a tale with themes as old as those in the story of Cain and Abel, and as American as Of Mice and Men. It covers a great deal of ground. And they kept it in their repertoire for twenty four years.

If there is a connection, then it’s not *just* about Altamont of course. But it seems to me a near impossibility that “Jack Straw”, the only Dead song that clearly fits our loose definition of a murder ballad, written sometime in the year or so after Altamont, was not informed to *some* degree by the murder of Meredith Hunter and the events that then unfolded.

We can’t deny that Altamont was still a ringing chord for Hunter, Weir and the Dead in ’70 and ’71. And in “Jack Straw” we see all sorts of strings that resonate; revulsion at meaningless violence, deep vulnerability, a wish to escape and a quest for ultimate freedom, desperate helplessness in the hands of fortune, and resignation at doing what one must do to survive.

Yes, yes, I know; I’m long on imagination and short on evidence. Hunter or Weir never said or wrote anything of which I’m aware that supports my claim. (If you know of something, please share!) But after all, Robert Hunter declared that he is more interested in knowing what meaning a listener derives from one of his songs than in telling him or her what it should evoke. So I can’t really go wrong here!

Please, don’t misunderstand me. “Jack Straw” can be about all sort of things. It’s got universality. For me it’s been about letting go of old friends with whom I could no longer relate, or who weren’t ever really friends at all. It’s been about being in trouble despite trying to do the right thing. It’s been about starting anew and giving up naive dreams. It’s been about my fear of death.

It’s all in there. And those meanings are, for me, more important than anything historical.

And I don’t mean to suggest that there’s a one to one decryption matrix, wherein the murder of the watchman or Shannon corresponds with a specific event on the timeline which begins with December 6, 1969. In fact, if there is any such direct connection, I’d say that Jack and Shannon are more like the hippies and the Angels, both outlaws in some very real ways. Perhaps Jack’s murder of Shannon is a metaphor for the counterculture’s break with the Angels, with whom they’d shared some level of camaraderie until Altamont.

Really though, I only feel comfortable in saying that those fictions that make up “Jack Straw” must have for its writers and performers evoked layers of rich meaning to fill the psychic spaces hollowed out by the events that shaped their lives – just as those fictions still do for me and anyone who has the ears to listen.

Dude, that’s what murder ballads do.

Coda

Just for fun, and for nostalgia’s sake, I’m including a short interview here with Jerry Garcia. It’s not about anything so grandiose as ‘the Sixties’ or as serious as murder. But it does connect strangely to some of what we talk about here in this blog. Even if you don’t think so, I think you’ll enjoy!