Still He Keeps Singing: “I Ride an Old Paint”

“I am here when the cities are gone.

I am here before the cities come.

I nourished the lonely men on horses.

I will keep the laughing men who ride iron.

I am dust of men.”

— from “Prairie” by Carl Sandburg

Hoolihans and poolroom fights

When we wrote our “My First Murder Ballad” post, mine was “John Henry,” performed by The Easy Riders. That song edged out the cowboy classic “I Ride an Old Paint” for first place by just one track. The Riders’ Wanderin’ (1959) was probably more influential for my lifetime of singing than any other album. When I was listening to it in the ‘70s, old-timey Westerns were regular fare on Saturday television. “I Ride an Old Paint” was then and is now an evocative song of the West; a fitting, if generally more peaceful, complement to those movies. It is also a work song, a murder ballad, and a conversation with death, all packed into three verses, two chords, and one octave. You can find fancier arrangements, but a simple I-V chord structure will do. It is lonesome without being “high lonesome.”

“I Ride an Old Paint” offers a smattering of cowboy lingo, which adds to its mystique as the song ambles along. The first and third verse sing from the perspective of a working cowboy. The middle verse tells us that Old Bill Jones’s wife died in a poolroom fight. To my ears back then this was equal parts romantic, sad, and hilarious. Check that, I’m pretty sure it was mostly hilarious – risky and incongruous.

In today’s post, we’ll unpack some of the cowboy jargon, ride down a few trails of the song’s history, and consider how “I Ride an Old Paint” feels like the musical equivalent of that reliable old pony. The song carries us through the West, and along a few other kinds of journeys. Appropriate to my autobiographical introduction, The Easy Riders’ performance will help get these various “dogies” herded and underway.

Terry Gilkyson and The Easy Riders applied a late ’50s pop aesthetic to the folk songs on Wanderin’. They often inserted invented choruses in “old chestnut” ballads. “I Ride an Old Paint” presents an exception to their modus operandi. They play it at a brisk waltz tempo, and apply some necessary verbal syncopation to the singing. By comparison, though, they approach the song with an implicit earnestness, almost a reverence.

(Lyrics are in the Sandburg link below. Recordings embedded through YouTube links in the post will be included in a Spotify playlist at the end.)

Songbags and saddlebags

The Easy Riders were not the first to find reverence in “I Ride an Old Paint.” Carl Sandburg first published the song in The American Songbag (1927). He introduces it as follows, explaining how the song reached him, first literally, then figuratively:

“This arrangement is from a song made known by Margaret Larkin of Las Vegas, New Mexico, who intones her own poems or sings cowboy and Mexican songs to a skilled guitar strumming, and by Linn Riggs, poet and playwright, of Oklahoma in particular and the Southwest in general. The song came to them at Santa Fe from a buckaroo who was last heard of as heading for the Border with friends in both Tucson and El Paso. The song smells of saddle leather, sketches ponies and landscapes, and varies in theme from a realistic presentation of the drab Bill Jones and his violent wife to an ethereal prayer and a cry of phantom tone. There is rich poetry in the image of the rider so loving a horse he begs when he dies his bones shall be tied to his horse and the two of them sent wandering with their faces turned west.”

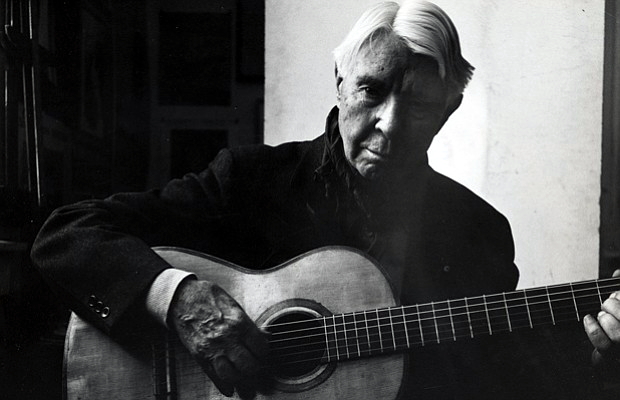

Here is Sandburg’s performance, recorded 11 years after he published the sheet music:

(Lyrics here. You can download an mp3 of the song from PBS here.)

“I Ride an Old Paint” either eluded collection by John Lomax in his seminal 1910 Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads, or it had not yet been created. It also does not appear in N. Howard Thorp’s Songs of the Cowboys, which Thorp first self-published in 1908. Neither Lomax nor Thorp added it in subsequent editions to their works through 1921. I’ve seen speculation, but not yet evidence, that the song originated in the heyday of the American cowboy. This period was only about 25 years in the late 19th century.