You Can’t Win a Race with a Cannonball: Goya, Guernica & My Son John

A dillar a dollar a ten o clock scholar blow off his legs and then watch him holler.

— Dalton Trumbo: Johnny Got His Gun

I saw it.

— Francisco Goya

Bayonet and Musket

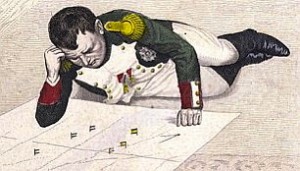

In 1807, Napoleon Bonaparte launched a seven-year military campaign against England and Portugal for control of the Iberian Peninsula. The following year he turned on his nominal ally, Spain. Part of a broader war of European conquest that had netted the French Revolutionary hero-turned-tyrant control of over half the continent, the “Peninsular War” marked the beginning of the end for the Empire Francais and its supercilious commander. Compounding defeats ensued, culminating in the 1815 Waterloo disaster and his Atlantic island exile and death.

There was poetry, for some, in his comeuppance. While the egalitarian principles of the former Jacobin – who had transformed the French Republic into a dictatorship by political sleight-of-hand in 1799 and crowned himself Emperor in 1804 – had always been less genuine than expedient, idealists of the era were still appalled by his brazenness. A disgusted Ludwig van Beethoven – whose original title for Eroica, his symphonic paean to the revolutionary zeitgeist, had been Buonaparte – famously excised the despot’s name from the score when informed of his self-coronation. Others found poetry, however dark, in the tumult engendered by his hubris. In Spain, his Iberian land grab toppled the monarchy and plunged the nation into the internecine chaos of the Guerre de la Independencia Española. While a more modern, democratic Spain eventually emerged, a storm cloud of disarray and extreme violence – documented with harrowing intensity by the artist Francisco Goya in works like Los Desastres de la Guerre (1810-1820) – enveloped the country for six miserable years.

There was poetry, for some, in his comeuppance. While the egalitarian principles of the former Jacobin – who had transformed the French Republic into a dictatorship by political sleight-of-hand in 1799 and crowned himself Emperor in 1804 – had always been less genuine than expedient, idealists of the era were still appalled by his brazenness. A disgusted Ludwig van Beethoven – whose original title for Eroica, his symphonic paean to the revolutionary zeitgeist, had been Buonaparte – famously excised the despot’s name from the score when informed of his self-coronation. Others found poetry, however dark, in the tumult engendered by his hubris. In Spain, his Iberian land grab toppled the monarchy and plunged the nation into the internecine chaos of the Guerre de la Independencia Española. While a more modern, democratic Spain eventually emerged, a storm cloud of disarray and extreme violence – documented with harrowing intensity by the artist Francisco Goya in works like Los Desastres de la Guerre (1810-1820) – enveloped the country for six miserable years.

Among those fighting the French in the Peninsular War were nearly a hundred thousand Irishmen, representing a staggering 40% of the British Army. England had no military draft, so recruitment was aggressive and disproportionately directed at the lower classes. This included much of the Emerald Isle, where economic strife made military life slightly more attractive than crushing poverty or debtors’ prison. Inductees signed up for seven-year stints, their low but steady wages augmented by “beer money” allowances, but received little respect for their service: though Irish-born, Arthur Wellesley – 1st Duke of Wellington, British field marshal, and nemesis of Napoleon (whom he trounced at Waterloo) – referred to the troops as bastards, drunks, and “the scum of the earth.”

Among those fighting the French in the Peninsular War were nearly a hundred thousand Irishmen, representing a staggering 40% of the British Army. England had no military draft, so recruitment was aggressive and disproportionately directed at the lower classes. This included much of the Emerald Isle, where economic strife made military life slightly more attractive than crushing poverty or debtors’ prison. Inductees signed up for seven-year stints, their low but steady wages augmented by “beer money” allowances, but received little respect for their service: though Irish-born, Arthur Wellesley – 1st Duke of Wellington, British field marshal, and nemesis of Napoleon (whom he trounced at Waterloo) – referred to the troops as bastards, drunks, and “the scum of the earth.”

Many of these despised sons of Eire bore bayonet and musket against the French on May 3-5, 1811, when British-Portuguese forces routed an attempt to retake the town of Almeida at the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro. Among their number may have been a soldier named John, or Ted, whose surname may have been McGrath (pronounced “McGraw”), and who may have returned from his seven years’ service alive but missing his legs.

Life and Limb

My son John was tall and slim

And he had a leg for every limb

But now he’s got no legs at all

They’re both shot away with a cannonball

(Note: all italicized lyrics from Boiled in Lead: “My Son John”)

“Mrs. McGrath,” or its shorter variant, “My Son John” (or “Ted”), is an antiwar song – a folk ballad generated by a specific conflict that transcends its particulars to denounce war in general. The song uses explicit violence – or more accurately, its outcome – to warn young men that the glories of war are at worst a lie and a sham, at best an unfair trade of a potentially robust future for the dubious honor of risking life and limb for reasons unclear, unknown, or unconvincing.

In the early 19th century this was still a radical idea. The young man who goes to war and returns irremediably changed – his youth lost, innocence shattered, soul haunted – is a motif perhaps as old as war itself. But its use to question the whole enterprise of war was distinctly modern – while scattered anti-war traditions existed previously in the west, it took the post-Enlightenment era’s willingness to challenge inherited truths to give wide voice to such a notion. Goya was a pivotal figure in this shift: his terrifying evocations of Mars run amok in Desastres didn’t merely question the justness of the Peninsular War, but – for the first time in western art – that of war itself. His peculiar insider/outsider circumstances – official painter of the Spanish court before the monarchy’s fall, firsthand witness to the atrocities of the invasion in its aftermath – informed his vision. Exposed equally to the ruthlessness of power and the retaliatory violence of its victims he came to see civilization – two decades before Nietzsche’s birth – as a fragile façade that masked an inchoate brutality. In his work, he let the mask slip.

In the early 19th century this was still a radical idea. The young man who goes to war and returns irremediably changed – his youth lost, innocence shattered, soul haunted – is a motif perhaps as old as war itself. But its use to question the whole enterprise of war was distinctly modern – while scattered anti-war traditions existed previously in the west, it took the post-Enlightenment era’s willingness to challenge inherited truths to give wide voice to such a notion. Goya was a pivotal figure in this shift: his terrifying evocations of Mars run amok in Desastres didn’t merely question the justness of the Peninsular War, but – for the first time in western art – that of war itself. His peculiar insider/outsider circumstances – official painter of the Spanish court before the monarchy’s fall, firsthand witness to the atrocities of the invasion in its aftermath – informed his vision. Exposed equally to the ruthlessness of power and the retaliatory violence of its victims he came to see civilization – two decades before Nietzsche’s birth – as a fragile façade that masked an inchoate brutality. In his work, he let the mask slip.