“Betty and Dupree” – A Digital Compendium, Part 2 – The Classics

So, down to the jewelry store packing a gun

he said, “Wrap it up, I think I’ll take this one.”

“A thousand dollars please,” the jewelry man said.

Dupree he said, “I’ll pay this one off to you in lead!”

The Grateful Dead told the tale of this robbery and murder in one of their best-loved early ballads, “Dupree’s Diamond Blues.” In Part 1 we took a closer look at their song and found that it holds a unique place as the final link in a chain of mostly African-American bad man ballads we can loosely group together under the title “Betty and Dupree”. The Dead’s version is the most well-known of the lot now, but today we’ll trace the song from its first days as a bad man ballad on the threshold between oral tradition and popular recorded music, through the era of Blues, Jazz and the Big Band, and into the Atomic Age where it found rebirth both in Rock and Roll music and that of the Folk Revival.

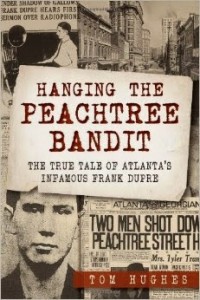

Before we do that, you need to realize that it’s a true story. Now, I don’t mean to say that every line of every ballad about Dupree and Betty is true – far from it. But all of the ballads draw their inspiration from an actual series of events, which we covered in some detail last week too. You can go back to that post to get the basics, drawn from Tom Hughes’s Hanging the Peachtree Bandit: The True Tale of Atlanta’s Infamous Frank DuPre. For those who want more, that short and inexpensive book will satisfy any seeker with a engaging history of the crime and its aftermath. Here’s the skinny again though, in case you’re too busy to dig into it or you’re just looking to get to the music below.

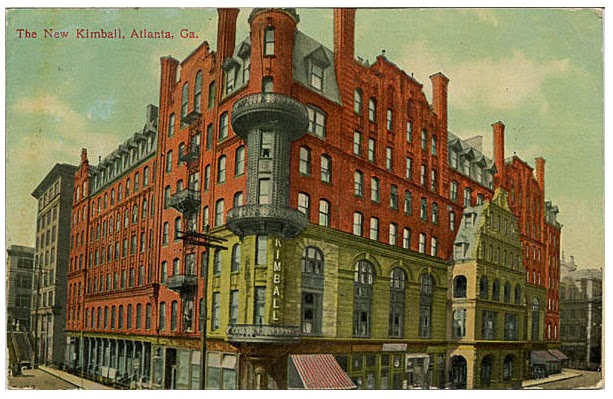

Frank DuPre, an eighteen year old who’d just begun trying his hand at petty theft in Atlanta where he found himself out of work, fell hard for seventeen year old Betty Andrews. He spent a good deal of his recently ill-gotten gains on her over the course of a week, and she told him that if he wanted to keep courting her that she expected more nice things, even a diamond ring. On December 15, 1921, Frank downed a half-pint of moonshine and soon thereafter paid a visit to Kaiser’s Jewelry, where he managed to get a manager to show him an immensely expensive diamond ring. He snatched it and ran for the door, where he slammed in to Irby Walker, a Pinkerton agent the store manager had just hired for extra holiday security. After initially falling backwards into the store, DuPre produced a .32 Colt ‘hammerless’ from his pocket and dispatched Walker, a young father of one, to an early grave. He bolted down Peachtree Street and wounded another man badly before finally making good on his escape and skipping town that evening by promising a hefty sum to a taxi driver with a Packard Twin Six. After pawning the ring in Chattanooga and spending several weeks on the run, the law caught up with Frank. He was quickly tried and convicted, and eventually hanged on September 1, 1922 after failed attempts for both appeal and clemency.

The Kimball House, behind which DuPre wounded a man after killing Irby Walker in Kaiser’s Jewelry Postcard ca. 1912, public domain

The case was a nine month media spectacle, in a way we today might find familiar. Indeed, Frank gathered quite a following of advocates and well-wishers before his execution. They sometimes expressed something in common with the singers of the ballads we’ll hear today – Dupree was a good man lead astray by a bad woman. However, Tom Hughes proves with all available evidence that this is at best a misguided interpretation of how it all went down. It is, at worst, a downright lie at least as old as the story of Adam and Eve.

Betty Andrews knew about the robbery after the fact and didn’t report it, but she had nothing to do with planning it and she cooperated with police in apprehending DuPre. She was a troubled, dull youth. But she didn’t ask Frank to rob or kill for her. And yet, that is exactly the rap she got. I’ll deal with that angle in the coda below, but for now it’s time to get to the mechanism of that popular indictment – the long string of ballads that make up our digital discography of “Betty and Dupree”.

Betty and Dupree – A Digital Compendium, Part 2 – The Classics

Earliest Printed Sources – “Jelly roll’s gonna be your ruin…”

As we know the date of Frank DuPre’s crime and execution, we can zero in pretty well, if not precisely, on the origins of this ballad. Interestingly, though the event that inspired it came in the early days of widespread recorded music, this ballad has one foot squarely in the world of the oral tradition.

I’ll get to that in a minute, but let’s get the catalog information down first. Waltz and Engle’s Traditional Ballad Index links to this ballad as “Dupree“ and provides citations for many of the print collections that include it. Malcolm Laws gave it catalog number I11 in the most well know of these, his seminal work Native American Balladry. As for the 21st century, the Roud Folksong Index catalogs it today as #4179 with 13 citations, and Jerry H. Bryant includes “Dupree” as one of the thirty “prototype” bad man ballads (of the “police” type) in his 2003 work Born in a Mighty Bad Land: The Violent Man in African-American Folklore and Fiction.

Interestingly, Waltz and Engle’s online database fails to cite the earliest known print reference to the ballad, in Howard Odum and Guy Johnson’s 1926 Negro Workaday Songs, now in the public domain and available at Internet Archive (see pp. 55-59.) This is a most interesting starting point, as it’s clear from their inclusion of two vastly different but clearly related variants that this song was already being mixed, matched, and reassembled in ‘the folk process’ within four years of Frank DuPre’s execution. Notably, this was happening exclusively among African-American balladeers though Frank and Betty were both white.

Now, there is an Anglo-American ballad based on the robbery and execution, which Malcolm Laws cataloged as E24. “The Fate of Frank Dupree” was recorded by Blind Andrew Jenkins and released in 1925 on Okeh Records #40446, as the B-side to another ballad about famous contemporary Georgia murder we have yet to cover in this blog, that of Mary Phagan (recorded by Rosa Lee Carson.) Hughes tells us that Jenkins wrote the lyrics, inspired by local headlines, soon after DuPre’s execution, and he prints them in full in his 2014 book. It is entirely clear when one reads them that, as indeed Odum and Johnson noted in 1926, they are not at all related to the African-American bad man ballad.

Clearly then, Odum and Johnson collected an independent ballad inspired by DuPre’s crime and hanging – a ballad born in the waning days of the oral tradition. Luckily for us, it was also born in the early days of commercial recording and the ballad found its place on wax only five years after the publication of Negro Workaday Songs. Where Jenkins’s nearly extinct Anglo-American ballad more accurately blamed DuPre’s affinity for alcohol and the ‘sporting life‘ as the cause of his downfall, this black man’s song tells a better tale, unfair for sure but as old as the Bible, about a wicked woman that turned a good man to the bad.

Dupree was a bandit

He was so brave and bol’

He stoled a diamond ring

for some of Betty’s jelly roll.

Earliest Recordings, 1930 – 1939: “I give you most anything…”

The two earliest commercially recorded versions of the Dupree ballad were both waxed in late 1930 and released in 1931. One features a piano and the other an acoustic guitar.

Kingfish Bill Tomlin cut his track “Dupree Blues” in November 1930, and so his is technically the earliest version on record. It was released as the a-side of Paramount 13057. Hughes claims in his recent book that the track is lost but, thankfully, such is not the case.

“Dupree Blues” by Kingfish Bill Tomlin – YouTube

Lyrics for “Dupree Blues” by Kingfish Bill Tomlin

Though the singer blames Betty (or Bertie) for the crime and so perpetuates the key falsehood of the case, the lyrics include at least two interesting scraps of truth from the story of Frank DuPre. Kaiser’s jewelry store was indeed the scene of the crime (on Peachtree Street though, not Decatur) and the real DuPre did gun down a “one-eye”, which Hughes found was contemporary slang for a Pinkerton (with an obvious double-entendre, I might add.)

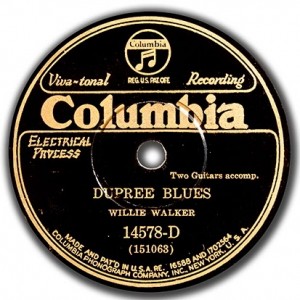

Blind Willie Walker, a widely respected Piedmont blues player with almost no recorded legacy, in December of 1930 cut the early ‘Dupree’ track that became most influential. Hughes notes that Walker played with Sam Brooks for this session in Atlanta, at Columbia’s studio on Peachtree Street of all places! The record was released as Columbia 151063.

“Dupree Blues” by Blind Willie Walker – YouTube

Lyrics for “Dupree Blues” by Blind Willie Walker

Interestingly, while the Mudcat citation I linked above with the lyrics has Dupree taking a taxi back to “Main” (street), Hughes transcribes the lyrics in his book as “Hired him a taxi, said ‘Can’t you drive me back to Maine?'” This is the better transcription and reflects something of the true history – Frank DuPre hired a taxi to take him to Chattanooga where he pawned the ring for which he killed. Maine, Hughes argues convincingly, gives the flavor of the historically accurate long flight from Atlanta, but makes for an easier rhyme. Again then we see the truth echoing in the ballad even alongside the consistent and unfair blame assigned to Betty.

Interestingly, while the Mudcat citation I linked above with the lyrics has Dupree taking a taxi back to “Main” (street), Hughes transcribes the lyrics in his book as “Hired him a taxi, said ‘Can’t you drive me back to Maine?'” This is the better transcription and reflects something of the true history – Frank DuPre hired a taxi to take him to Chattanooga where he pawned the ring for which he killed. Maine, Hughes argues convincingly, gives the flavor of the historically accurate long flight from Atlanta, but makes for an easier rhyme. Again then we see the truth echoing in the ballad even alongside the consistent and unfair blame assigned to Betty.

This wasn’t strictly a man’s ballad though. Georgia White recorded it twice, once in 1935 as “Dupree Blues” (on YouTube – with lyrics) and once in 1936 as “New Dupree Blues” (on Spotify – with lyrics) backed up with some excellent guitar work by Les Paul. Hughes points out some of the interesting lyrical changes in her versions, with a taxi ride to Memphis (not quite his true destination of Chattanooga, but closer than Maine) in the 1935 cut, and Dupree’s arrest in Detroit while checking for mail in the 1936 variant, which squares fully with history.

I note one other most curious point as well. Dupree robs the jewelry store because “he didn’t want Betty to know he didn’t have a thing.” She never asked him to steal in this version and she is not overtly painted as “wicked” except by Dupree himself. She brings him lunches to “Big Rock Jail“, the place of the real DuPre’s incarceration as Hughes points out, though he mistakenly attributes the lyric to Teddy Grace, who actually covered White’s version. Dupree asks for whiskey instead and mourns that Betty has made him “her doggone slave”. Says him! To my mind, White (or the writer of the lyrics, if they were not her own) put a careful spin on the tale that is sympathetic to Betty. It’s really not even that subtle. Dupree stole because he didn’t want to show Betty his poverty, but then he blames her for his own violence after the fact, while she’s bringing him meals no less. This version of the tale makes it clear – it wasn’t Betty’s fault!

Interestingly, White’s 1936 cut leaves out both the murder and Dupree’s subsequent execution altogether. It adds the bit about Dupree’s arrest, and gets right the fact that he combed the newspapers for information about the police manhunt. However, the gains it makes in historical accuracy are lost in the incomplete and bowdlerized narrative. That one is really more about the music.

By 1937 at the latest, the ballad was making its way into white musicians’ repertoires. Woody Herman cut a version that year (on Spotify) that sparingly mixes and matches lyrics we’ve heard so far and ends with the unique and rather sterile line “Now Dupree’s going so far away, he’s never gonna see the light of day”. His record is mostly about the music as well, and his orchestration is anything but sterile. Teddy Grace recorded a cut in 1939 (on Spotify, on YouTube). Her lyrics match those of Georgia White’s first cut exactly. Given that we also find a similar version in a women’s prison that same year (see below), it seems more than coincidence; women sang this ballad differently, in a way that saw Betty in a more accurate and sympathetic light.

Prison Blues 1926 to 1939 – “She’s trying to make ninety-nine…”

Even before World War II this ballad was crossing both geographic and racial boundaries, and we’ll see below that it did so for decades longer. Hughes supports an argument made by others that part of the staying power of the ballad is that it transcends race with deeper universal themes. This obviously must be granted, but I think it misses something about race and the ballad’s origins that’s hiding in plain sight, and which in part explains why a ballad about the exploits of two white teenagers spread so quickly, and almost exclusively at first, among African-American songsters.

To illustrate my point, note that Odum and Johnson’s second variant cited above was collected on the chain gang. We’ve already seen the deep significance of black prison blues and bad man ballads on the chain gang in this blog both with “Stagolee” and “Little Sadie“. No doubt, the “Betty and Dupree” narrative fit well in that genre as another coded expression of resistance to the corrupt and unjust system of de jure slavery that endured in the south for a century after the Thirteenth Amendment. If you’re interested in that code in detail, you can go back to the other two posts I’ve linked. Suffice it to say there was great use for any song that lyrically placed blame at another’s feet – in a way armed white guards would let pass – for African-Americans who found themselves at hard labor for petty misdemeanors or often for no legal reason at all. The ballad’s literary themes may transcend it, but its application in the hell of a southern prison was all about race.

Indeed, even while it was finding its way onto records and radio waves in the 1930s, John and Alan Lomax discovered at least two more examples of the ballad behind bars with black folks during their famed collecting tours of southern prisons. They included an example from 1936, transcribed from the singing of Walter Roberts at the old Raiford State Prison in Florida, in their classic Our Singing Country (starting on page 328 linked here, but make sure to go to the next page to get the rest of it.)

Their recording of Buena Flint (aka Buena Flynn) from 1939, also at Raiford, has been digitized and is available online (click ‘play mp3’) from the Library of Congress. (Lyrics) It’s worth the click because you’ll hear that even in prison it wasn’t just a man’s song; Flint was an inmate in the women’s dormitory. The lyrics are likely derived in part from White’s 1935 recording or Teddy Grace’s cover from 1939 – Dupree robs the jewelry store because he doesn’t want Betty to know he’s poor. The narrative diverges after that though. When robbing the jewelry man, Dupree fingers Betty as the cause of his crime. Then in the last verse, we assume that Betty is waiting out Dupree’s ninety nine year sentence. But there can be absolutely no doubt that Flint is really singing about herself and mourning her lot.

I said six months ain’t no sentence

Baby, two years ain’t no time

Look at poor little Betty,

she’s trying to make ninety-nine.

We know from our work with other bad man ballads that such is how the prison blues work – identification with the bad man (or woman) in the narrative gives the inmate a way to sing out pain and rage at the injustice of his or her situation. It’s a chance to survive psychologically. So despite the ballad’s universality, we shouldn’t ignore that the evidence clearly demonstrates that “Betty and Dupree’s” early vitality comes at least in part from this wholly African-American experience.

The 1940’s and 1950’s – “Betty told Dupree…”

“Betty and Dupree” the song came of age a quarter century or so after the real Frank DuPre’s execution. The ‘blame Betty’ narrative became dominant and the most recognized African-American versions of the ballad were recorded during those decades.

Interestingly, a less well known 1944 example from “Guitar Slim and Jelly Belly” (Alec Seward and Louis Hayes) strips the narrative away and only opens suggestively with the classic “Betty told Dupree” verse before falling back on the standard blues formulation of ‘if I’d only listened to what Mama said.’ The Dupree story was so well-known that its invocation in the first verse is enough, and the term “ballad” cannot be justified in describing this particular variant. It’s just pure blues emotion, and it makes for some great listening.

Lyrics for “Betty and Dupree” by Guitar Slim and Jelly Belly

In 1945 Josh White, at the height of his career before being blacklisted during the McCarthy Era, recorded a version of the ballad that was released on Disc Records, a label managed by parent Folkways Records, as part of a four song album called Josh White: Women Blues. The 1945 track has made it on to at least two Smithsonian-Folkways compilations and so is now probably one of the more commonly heard versions of the ballad.

One of White’s earliest musical role models was in fact Willie Walker and, though White’s version is quite different from Walker’s linked above, it is a wonderful homage to his hero. The recording though is, in its own right, a rich and innovative retelling of the old narrative. We see that by the end of World War II, all sorts of embellishments adorned the historical tale that nevertheless still survived piecemeal in the ballad.

(See White's discography for more information, as this is only the first of several versions of the ballad he released. Hughes seems to confuse it with White's rather different 1956 track from The Josh White Stories, Vol I, but the track on the compilation Classic African-American Ballads he references in his book (and which is linked above) is the same as on Free and Equal Blues, the liner notes to which cite "Betty and Dupree" as the 1945 track from Disc.)

“Betty and Dupree” by Josh White – YouTube

Lyrics for “Betty and Dupree” by Josh White

The great Brownie McGhee cut his classic version of the ballad ten years later for Folkways in 1955, for his album Blues. Like White, McGhee would not be satisfied recording just one version of the ballad over his career, but this is probably his most well-known today. It is truly beautiful, from the first note to the last.

“Betty and Dupree” by Brownie McGhee – YouTube

Lyrics for “Betty and Dupree” by Brownie McGhee

Commercially, “Betty and Dupree” became a chart making hit for two artists on either side of the Atlantic in the 1950’s as well, though their versions are perhaps the least satisfactory for those of us in search of great storytelling in song. Chuck Willis, “The King of the Stroll”, took his 1957 recording to #33 on the Pop chart and #15 on the Rhythm and Blues chart in the U.S., peaking in March 1958 only a month before he died of peritonitis. His version starts with Betty’s fateful request for a diamond ring, but it is devoid of any crime or violence and it has a happy ending, so it is essentially a sappy love song. That’s not our usual fare at Murder Ballad Monday, but Willis’s classic must be included for the sake of cultural literacy!

“Betty and Dupree” by Chuck Willis – YouTube

Lyrics for “Betty and Dupree” by Chuck Willis

1958 also saw legendary British skiffle musician Lonnie Donegan make it to #11 on the British charts with his version “Betty, Betty, Betty.” He didn’t clean up the lyrics like Willis; indeed, he used Josh White’s 1945 lyrics with only minor changes. But the skiffle treatment on this song just doesn’t cut it, for me at least. To each his own though, so be your own judge.

“Betty, Betty, Betty” by Lonnie Donegan – YouTube

The Folk Revival – “See what tomorrow brings…”

The ten years prior to the Grateful Dead’s recording of “Dupree’s Diamond Blues” in 1969 saw an explosion of covers of “Betty and Dupree” from both white and black performers, all ultimately connected to the commercial success of the Folk Revival. There is even an outrageously funny version by MBM’s favorite un-classifiable comedienne songstress, Judy Henske! Indeed there are too many from that decade to link to here, and they are often rather uninteresting derivatives of tracks we’ve already heard; but I’ve included three of the genuine sort below to give the flavor.

On that last point, I’ll grant that Dave Van Ronk did nothing particularly new with the ballad. Yet, his faithful 1959 cover of Brownie McGhee’s version, included on Van Ronk’s influential album Ballads, Blues, and a Spiritual, rises to the level of original art in imitation. Certainly it was then and still is widely appreciated among folk music enthusiasts.

Harry Belafonte was of course more popular than Van Ronk at the time and as well across a wider swath of the American public. In 1962 he cut an innovative and experimental version, that to my ear mixes American with African and Caribbean musical elements, for his album The Many Moods of Belafonte. At this point I don’t have the liner notes in front of me to know whether he and his collaborators creatively rewrote the story for that production, or if he used an older version from the tradition that he discovered in print or on some recording that is currently obscure. Whichever the case, this set of lyrics is perhaps the most compelling of the lot, and seems a rare exception to the “wicked Betty” narrative from the latter days of the ballad’s life.

Lyrics for “Betty an’ Dupree” by Harry Belafonte

Peter, Paul, and Mary also managed to do something new with the aging ballad for their popular 1965 album See What Tomorrow Brings, the title for which is obviously drawn from “Betty and Dupree”. Their take is certainly closer to Rock and Roll than traditional folk or blues, but it works quite well.

“Betty and DuPree” by Peter, Paul and Mary – YouTube

Lyrics for “Betty and DuPree” by Peter, Paul and Mary

So there you have it! Well, not really. I haven’t even covered half of what I’ve got on my Spotify playlist, but I’ve hit the big ones. Follow the playlist and check out anything there anytime you want!

Coda: “Ask that woman: she knows why.”

It seems clear enough that, in the end, this ballad persists for the reason Hughes and others rightly see as obvious: the themes, whether they square with the details of history or not, are universally appealing. But is it really the ‘old as the Bible’ misogynistic “wicked woman” narrative that ultimately fuels it?

We’ve seen without a doubt that, for the majority of the versions of the ballad we can know today including the one from the Grateful Dead we covered in our last post, that answer is ‘yes’. On the other hand, today we see enough evidence to say that several female performers, as well as some males, subtly reworked lyric elements of the ballad through the decades to shift blame away from Betty. In those versions, like Georgia White’s or Harry Belafonte’s, the narrative is equally appealing – a bad man who blames ‘his woman’ for him doing wrong all by himself.

As always, we see misogyny in our genre of choice. And, as always, we see more. I don’t know that I have anything more intelligent to say about it all today.

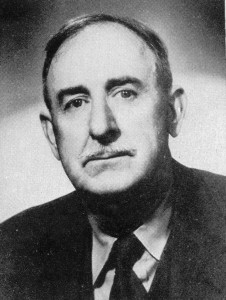

Still, Hughes finishes his book on DuPre’s sad story by noting what you may already have picked up on if you explored the first printed version from the Lomaxes. You’ll see at the top of the entry I linked above- “Tune from Walter Roberts, Raiford, Fla., 1936. Text from Langston Hughes, who heard it in Cleveland in 1936.” Yes, that Langston Hughes.

In fact, as Tom Hughes points out, Langston Hughes published a poem in 1941 (linked here) called “Ballad of the Killer Boy” that owes its narrative wholly to the ballad. The poem is also available on Google Books online. I copy it here knowing you can already find it online and I offer it in the spirit of fair use.

And how should you fairly use it? In your own poet’s heart of course, and in any way you wish. However, I want to ask a question before you read. Is Langston Hughes really blaming Bernice (Betty) for all the wrong done by the ‘killer boy’ here, or is he inhabiting the killer’s skin (as we often see in murder ballads) to make a deeper point about us all? If that’s what he’s doing, why not then the balladeer?

Ballad of the Killer Boy – Langston Hughes, 1941

Langston Hughes, 1936, by Carl Van Vechten

Library of Congress, public domain

Bernice said she wanted

A diamond or two.

I said, Baby,

I’ll get ‘em for you.

Bernice said she wanted

A Packard car.

I said, Sugar,

Here you are.

Bernice said she needed

A bank full of cash.

I said, Honey,

That’s nothing but trash.

I pulled that job

In the broad daylight.

The cashier trembled

And turned dead white.

He tried to guard

Other people’s gold.

I said to hell

With your stingy soul!

There ain’t no reason

To let you live!

I filled him full of holes

Like a sieve

Now they’ve locked me

In the death house.

I’m gonna die!

Ask that woman-

She knows why.