You can take down my old violin

|

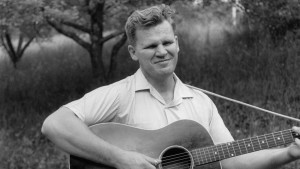

| Arthel Lane “Doc” Watson |

This is our third post this week on “Tom Dooley.” You can read the first here and the second here.

Introduction

My heart sank just a little after reading in John Edward Fletcher’s book about the Dula case that Doc Watson told a story of Grayson or “Bob Grayson” as a love interest of Laura Foster, and thus the third part of the “Eternal Triangle.” Fletcher explains that Betty Triplett Watson supposedly attended Ann Melton on her death bed, and was the source of Doc’s story. (It’s a bit confusing, as Fletcher identifies Betty as Doc’s grandmother in one passage and his great-grandmother in another.) This disrupted my “Doc Watson = authentic, Kingston Trio = ‘Disney-fied'” worldview. Multiple sources confirmed that the story was folklore, and incorrect folklore at that, and I was surprised to hear the erroneous tale attributed Watson. But, if memory serves, Watson was not averse to embellishing a tale or an introduction to make the story of a song more interesting.

Then I realized that Watson would not have spread the idea very widely at all before 1960, when he was “discovered.” The incorrect idea of “Grayson’s” romantic involvement with Laura Foster would have had wide currency because of the Kingston Trio version well before Doc Watson first played his version of “Tom Dooley” for Ralph Rinzler in the back of a truck on its way to Saltville, Virginia in 1960. Rinzler writes:

|

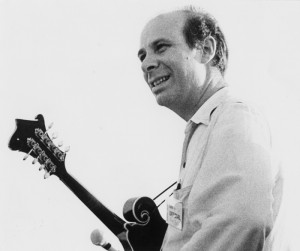

| Ralph Rinzler (photo by Diana Davies) |

“On the way to [Clarence “Tom” Ashley’s] daughter’s house where Tom had arranged for us to do the recording, I rode on the back of an open bed pick-up truck playing old time hoedowns on a five-string banjo. Within fifteen minutes, the truck stopped and Doc hopped in back saying, ‘Let me see that banjo, son.’ I handed it over. To my amazement, he deftly played and sang a local version of ‘Tom Dooley.’ The Kingston Trio’s 1958 hit record was still resonating across the nation. Doc’s version, unlike theirs, would have been compelling to anyone enlightened by Harry Smith’s Anthology.”

— (Liner notes to The Original Folkways Recordings of Doc Watson and Clarence Ashley: 1960 through 1962).

What I hope to do today is begin to single out some distinctive and/or historically significant performances, and a few musical themes. In the interest of time, I’m going to focus in this post only on the 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s, and hope to have the time an energy to come up to the more recent past in another post by tomorrow. If not, I will take up “Tom Dooley” in a later week.

In this post and the next, I also hope to find more than a few examples of how musicians have lifted this song, which can easily become rather monotonous and plodding, both musically and lyrically, and made something interesting out of it. I’m going to be selective, and inevitably incomplete. There are hundreds if not thousands of recorded tracks for “Tom Dooley.” It’s another song we will have to come back to eventually. As a special bonus for this post, however, I’ll draw a connection to some other, older material in the coda, which will potentially tie at least a small part of “Tom Dooley” back to old country balladry. So hang in there, folks.

“Sounds Like Old Times”

|

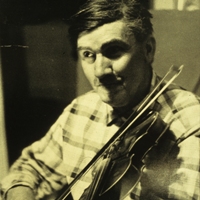

| Gaither Carlton |

“From the Anthology [of American Folk Music] we played an archaic-sounding recording of the ballad “Ommie Wise.” All listened intently. Gaither [Carlton, Doc Watson’s father-in-law], in his denim bib overalls, had come straight from his garden. As the song ended, tears were streaming down his face. No one spoke. Gaither sighed and said quietly, as though to himself, ‘Sounds like old times.'”…. The performance, recorded in 1927, was by George Banman Grayson, a blind fiddler who had died in an auto accident a few years after the recording session. G.B. Grayson was kin to Sheriff Grayson [sic] who had captured Tom Dooley not too far from where we were sitting at that moment. Members of Doc and Gaither’s family had known the principals in the Dooley case, and Banman Grayson himself had been a friend of Gaither’s.”

Doc’s deft touch on the six-string will get us off to an excellent start. “Tom Dooley” was the concluding track on his self-titled, debut release on the Vanguard label. Ralph Rinzler’s account, from which the above quote was excerpted, also tells the story of how much work it was to convince Doc Watson in 1960 that there was a market for the variety of local folk music surrounding his family. Perhaps it’s a measure of Rinzler’s success, or of Watson’s marketing savvy that he chose to include “Tom Dooley” on this release. Vanguard gave him free rein to pick his material on his early albums.

Doc Watson’s lyrics for “Tom Dooley.”

Watson’s version is far closer to the G.B. Grayson and Henry Whitter version than it is to the Kingston Trio’s, with one additional stanza. Musically speaking, Watson’s version is arranged to showcase his guitar wizardry, and to good effect. Although the lyrics follow a fairly logical narrative flow, Watson’s version is one of the key ones in suggesting to me that in many of the most musically successful versions, the lyrics are just an ornament to hang on the tune. The story is none too tight, and in many ways Watson’s arrangement is not so far off from a reel or the kind of “play party” song of the kind he would perform at Folk City with Jean Ritchie.

In other words, in terms of its lyric structure, “Tom Dooley” is less of a ballad than something like “Omie Wise.” The story’s not tight, the lyrics are repetitive, and the chorus keeps coming back around every verse or two. As a result, we have more poetic scenes than presented themselves in the actual true story, and avenues for deeper and older themes to creep into the song. More on that at the bottom of the post. But, in Watson’s version and others we’ll listen to, the basic song becomes a framework both for the artists’ musicianship as well as for new themes and verses applied to “improve” the story.

The Folk Boom and Echoes–The 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s

Probably the first artist to capitalize directly on the Kingston Trio’s success with “Tom Dooley” was the King of Skiffle, Lonnie Donegan. Paul Slade views Donegan’s decision to cut his own version of the song, also released in 1958, as probably the only stumbling block to the Kingston Trio’s version topping the U.K. charts. Donegan’s version is quite a bit livelier, not following the quasi-calypso cool of the Trio. He’s a little clumsy with the lyrics, but follows the same basic content as the Kingston Trio’s version. Donegan, though, does without the spoken word introduction describing “The Eternal Triangle.” His is the first version I can find that “elects” Grayson Sheriff.

Despite their musical differences, both the Kingston Trio version and the Donegan version are both influential steps in the evolution of rock and roll. It’s easier to hear this in Donegan’s Skiffle.

Back in the States, the New Lost City Ramblers quickly made efforts to bring “Tom Dooley” back to a more old-timey sound. This was the Ramblers’ niche, in the face of the Trio and other clean-cut “Great Folk Scare” acts. Their version, released in 1959, comes forward with a principled focus on delivering the song in a musically expert but overtly unvarnished way. Their lyrics hew rather closely to G.B. Grayson’s.

The New Lost City Ramblers’ Lyrics to “Tom Dooley”

The NLCR’s old-timey version contrasts strongly with some of the more domesticated versions turned out in the wake of the Kingston Trio’s 1958 break out hit. The opposite extreme is probably best exemplified by easy listening/exotica artist Les Baxter. Baxter turned out an instrumental version in 1960 on Young Pops, an album that includes a few other “murder ballad” favorites, including “El Paso” and “Mack the Knife.” Baxter’s tune strangely makes me nostalgic for an age I didn’t live through. It’s more of a movie theme version, with some skittering violin work toward the end suggesting a harrowing moment or two. Not really my cup of tea, but charming and somewhat amusing in its own way. Similarly, you might want to give Roger Williams’s “um-be-DEE-dum” piano version a listen, if you find yourself ambling along on a reluctant old nag, going down a not-so-happy trail.

OK, OK, I know Baxter and Williams are pretty far afield from our typical fare, but I couldn’t resist venturing to realms even more clean-cut and sanitized, musically speaking than The Kingston Trio. Theirs is not the most “Disney-fied” version of the tune out there.

|

| Sweeney’s Men |

So, as compensation, I’ll now move to my favorite version of “Tom Dooley,” brought to us by Ireland’s Sweeney’s Men. As I mentioned above “Tom Dooley” can easily become rather repetitive and plodding, both because of the lyrics and the tune. Much depends on the quality of the musicianship and the quality of the arrangement. I think Sweeney’s Men blow it out of the water on both these scores. It’s just my opinion, but they incorporate a deft mix of instrumentation, vocal harmony, and most especially vocal accent to create a very effective version. This one dances back and forth across the Atlantic from Irish pub seisiúns to Southern hoedowns, with gestures at both the instrumental breaks of the latter and the linked melody playing of the former.

Medley and Parody

There are relatively few female interpreters of “Tom Dooley.” I’ll get to a significant exception in a later post. There are also few effective piano performances. Her version, with its particular vocal phrasing is more indicative of 70’s pop, and incorporates a medley with “California Shoeshine Boys.” Frankly, I haven’t yet plumbed the thematic connections, so let me know if you see how these fit together. But, as piano-based versions go, I’ll take Nyro’s over Williams’s any day.

In 1973, Smithsonian Folkways released the Country Gentlemen‘s performance “Tom Dooley #2,” on Going Back to the Blue Ridge Mountains. The liner notes to the 2007 re-release of this album explain that soon after the Kingston Trio’s hit, the Gents released their own version “Rolling Stone,” as a single, with new lyrics by Pete Kuykendall. I discovered this information right before going to press, and haven’t yet been able to find a streamable version of it. Their “Tom Dooley #2” performance below is from an undated recording, but also likely from the early 60’s.

I haven’t found many bluegrass, as distinct from old-time, versions of “Tom Dooley,” and thought this performance worth including for that reason. The other reason to include it is that the verbal and musical banter throughout the performance present a relatively good-natured poking fun at the popularity of the Kingston Trio version. What the Gents provide sounds to me like something equivalent to Eric Bogle’s “Traditional Folksinger’s Lament (Do You Know Any Bob Dylan?)” in lamenting the trade-offs of popularity, originality, authenticity, and tradition.

However tongue in cheek, the Country Gentlemen’s performance is a tribute of sorts to what the Kingston Trio accomplished. I’ll have to leave off for now. We’ll start the next “Tom Dooley” post off with some more recent performances that take the song in some novel directions.

Coda — Fiddler on the Gallows

We haven’t yet discussed the real Tom Dula’s reputation as a musician, which is the basis of one of the G.B. Grayson stanzas also used in Watson’s version, but left out of the Kingston Trio’s. They also, curiously, leave Laura Foster out of the chorus, but that’s another story.

The verse in question, though, is this:

|

| The Ballad of Tom Dula author, novelist Sharyn McCrumb with Tom Dula’s fiddle |

You can take down my old violin

And play it all you please.

For at this time tomorrow, boys,

It’ll be of no use to me.

Some versions of the Dula legend describe him singing or playing music on his way to the gallows, or on the gallows itself. Some claim that one Dula song or another composed or performed by him. Some claim that the basic fiddle or banjo tune behind the particular strain of “Tom Dooley” we’re focused on this week was one played by Dula. There’s little evidence to back up these claims. Dula, though, was a known fiddle player and was promoted to “Musician” (drummer) during his service in the Civil War.

I’ve come to suspect that this particular verse is a subtle or tacit nod to another song we’ve discussed before, “MacPherson’s Rant,” which Tom introduced last fall. I doubt I can prove it, the comparison at least provides an evocative thematic resonance, despite the differences in the cases of MacPherson and Dula and the fact that the former wasn’t willing to let his instrument survive him. The “musician outlaw on the gallows” might have a certain cultural appeal given the thick Scottish settlement of Southern Appalachia and the Piedmont as well as the “musician as outlaw” theme we see peeking out from time to time.

The real James MacPherson was executed in 1700, and the songs about him emerged soon thereafter. I refer you back to Tom’s account. Robert Burns’s version, “MacPherson’s Farewell,” appeared in 1788. Mass emigrations from Scotland to the Americas would leave sufficient time for people familiar with the MacPherson story and their descendants to populate the South. I’ll grant you it’s a loose resemblance, but enough reason to tack on some good clips of “MacPherson’s Rant” to the end of this post. I’ll leave you with Adam McCulloch’s version and the Old Blind Dogs version that Tom featured.