The Yablonski Murder – Coal and Blood, Part 1

“Well it’s cold blooded murder friends, I’m talking about …”

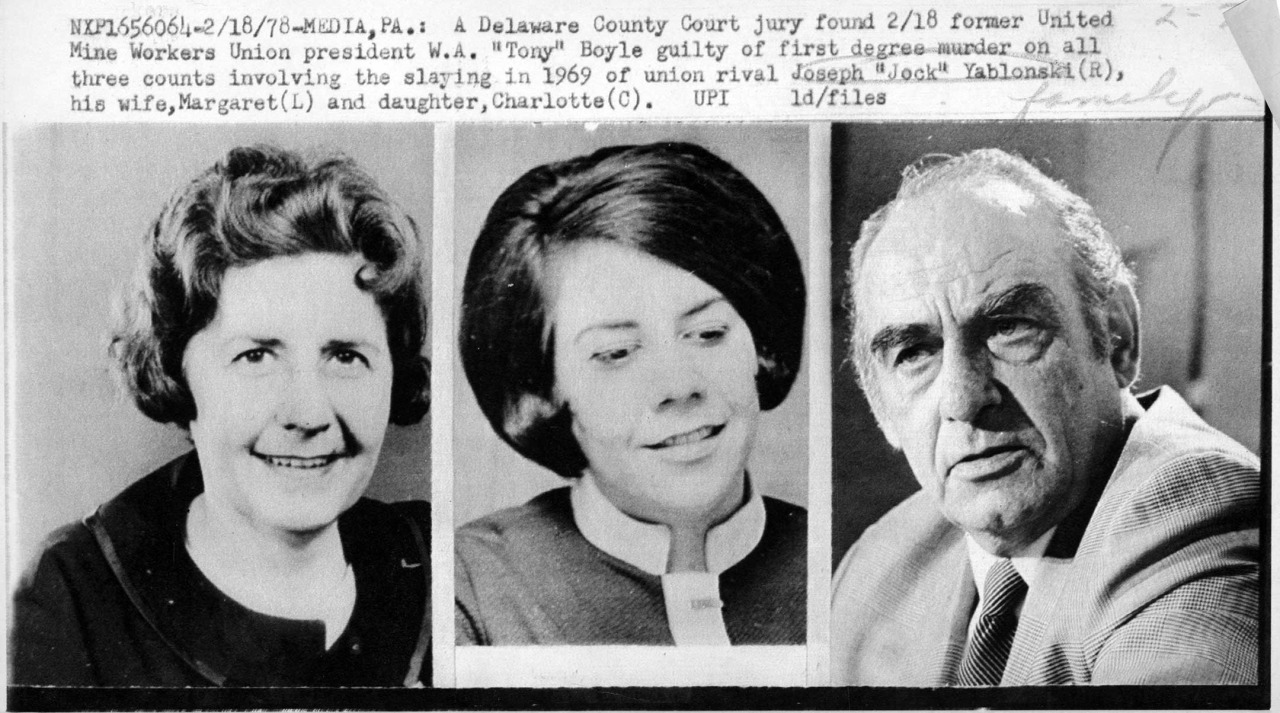

Such is the accusation that opens the angry chorus of “The Yablonski Murder.” Hazel Dickens penned the musical indictment in January of 1970 after she read the newspaper story describing what she rightly surmised was the assassination of union leader Joseph “Jock” Yablonski, his wife Margaret, and his daughter Charlotte on New Year’s Eve, 1969. Unlike many of the ballads we consider in this blog, this one deals in essential facts proven in multiple trials of the men and women convicted for involvement in the crime. Cold blooded murder it was indeed.

Clarksville, Pennsylvania is not too far from here

Coal miners were hoping for a brighter New Year

But for Jock Yablonski, his daughter, and wife

The New Year brought an ending to their precious livesWell it’s cold blooded murder friends, I’m talking about

Now who’s gonna stand up and who’s gonna fight?

You better clean up that union, put it on solid ground

Get rid of that dirty trash, that keeps a working man down(original third verse, 1970)

Well death bells were ringing, Jock knew very well

That’s stolen union money, and Jock just had to tell

‘Cause he wouldn’t take part in their dirty plans

So he paid with his life to help all mining men(revised third verse, reflecting Tony Boyle’s conviction)

Death bells were ringing as Jock made his plans

To save the U.M.W. for honest working men

So he ran against Tony Boyle, and all his dirty clan

But Tony hired a hit man, that was Jock’s fatal endWell Jock Yablonski was a coal miner’s friend

He fought for the rights of the working man

He begged the law to protect him, but they turned him down

Now Jock, his wife and daughter all lay beneath the groundOh Lord the poor miner, will his fight never end?

They’ll abuse even murder him to further their plans

Oh where is his victory how will it stand?

It’ll stand when poor working men all join hands

The song was perfectly clear to any American coal miner in 1969, but for us today it’s a bit sketchy. So what really happened? Though music rather than crime is our focus here at MBM, the background of these particular murders informs the core message of the song and is easy enough to relate in quick summary. The setting is the rough and tumble landscape of union politics in the United Mine Workers of America, in the first decade after the resignation of its controversial, autocratic, but highly effective president John L. Lewis. It is a tale of coal and blood, a drama of corruption and the strength of common working men and women dedicated to reform.

An aging John Lewis resigned from the presidency of the UMWA in 1960. Unfortunately, his popular successor Thomas Kennedy took ill in 1962 and died in 1963. That left acting President William Anthony “Tony” Boyle in a position to win election to the presidency of the union with Lewis’s blessing. Boyle had been in Lewis’s inner circle for many years and by all accounts was as dictatorial a leader, though with none of Lewis’s political savvy or personal charm. By 1969 it had also become clear to a large portion of the rank and file membership that Boyle was not nearly as committed to their well-being as Lewis. Grievances went unresolved, demands for local autonomy were met with iron fist tactics, and wildcat strikes as well as the grassroots organization for benefits and protections concerning Black Lung disease put Boyle on the defensive. Many members viewed him as being more sympathetic to the coal operators than to the miners, particularly after his callous reaction to the Farmington Mine Disaster. This all resulted in a campaign to wrest the presidency from Boyle in the union’s 1969 election, an insurgency led by the popular reformer and long-time UMWA organizer Joseph A. “Jock” Yablonski.

Yablonski and Boyle had already become bitter political and personal enemies by the late 1960s. In the summer of 1969, Boyle met with Yablonski and tried to force him to withdraw his candidacy. That meeting ended in a shouting match and, as evidence later established, a plot by Boyle to steal the election and neutralize Yablonski. In the election that December 9th, Boyle bested Yablonski by a large margin. But clear evidence of widespread fraud and intimidation convinced Yablonski to challenge the election at the federal level. Eventually Judge William B. Bryant overturned the sham election in May of 1972 and issued an order for a new one to be held under federal supervision that December. Jock Yablonski though would not live to see that day.

The story is made clear by evidence established in multiple courts. Boyle’s cronies, after ensuring their political victory, engineered the assassination to take place after the election so as to avoid suspicion of Boyle’s involvement. Three ne’er-do-wells took the job as amateur hit-men and were to be paid with $20,000 embezzled from the UMWA. After several abandoned attempts to carry out the executions, the three hapless gun thugs finally succeeded early on New Year’s Eve morning, 1969. They broke in to Yablonski’s home in Clarksville, Pennsylvania and shot Jock, his wife Margaret, and his daughter Charlotte. Jock’s son discovered the bodies several days later and a good deal of evidence at the scene led to the speedy capture of the three dull and sloppy killers.

Yablonski’s supporters knew that Boyle was ultimately to blame, though there was no evidence to provide for an immediate arrest. However, the federally supervised new election in December of 1972 resulted in Boyle’s defeat at the hands of another reformer, Arnold Miller. Boyle’s troubles multiplied. He was convicted in early 1972 of embezzling union funds and making several illegal campaign contributions, the largest being to Hubert Humphrey’s 1968 presidential campaign. By April of 1973, enough evidence had accumulated to indict Boyle for the Yablonski murders, and in April of 1974 he was convicted and sentenced to life in prison for those crimes. His conviction was overturned, but his second trial in 1978 ended with the same result as the original, and he died a prisoner in 1985. All told and including Boyle, seven men and women were convicted for direct participation in the brutal plot and two others served time for indirect involvement.

“Now who’s gonna stand up and who’s gonna fight?”

When Hazel Dickens heard the terrible news in early January of 1970, she as well knew that the blood was on Boyle’s hands, but she couldn’t prove it. She wrote in her 2008 book Working Girl Blues, “When I read about the murders in the newspaper, I was enraged. I sat down immediately and wrote the song, without very many details to go on.” If you listen to the song and read the lyrics above, there can be no doubt that even without knowing the details she saw it for exactly what it was – a political assassination. Eventually, as the facts were established in court, she rewrote the third verse to identify Boyle by name.

Even without Boyle’s name in the original, any coal miner would have known exactly who and what she was talking about. Indeed, one wonderful thing I’ve always found about most labor songs is that they need little analysis to establish exact meaning. It’s all right out there. Of course, Hazel’s song seems also to be a murder ballad proper so I can’t resist a bit of teasing things out. But let’s be clear – it stands on its own. It had to. Violence and murder in the coal fields has always occurred against a backdrop starkly black and white.

On the other hand, hearing Florence Reece sing her famous 1930s’ labor anthem highlights why “The Yablonski Murder” didn’t and doesn’t strike the same chord as does “Which Side Are You On.” Dickens may have tried to write her song in black and white, but it was during a time of workers’ civil war. Reece said once at a UMWA event in 1973 “You can ask the scabs and the gun thugs which side they’re on, because they’re workers too.” (see Harlan County USA) I don’t think she was talking about intra-union politics, but I imagine that her comment resonated for many in that audience because of it. When the officers of your own union hire the gun thugs to quash reform, those shades of gray can’t help but seep in like methane from a deep seam of coal. Again we have Hazel’s words from Working Girl Blues …

“One time right after the song was written and old wounds were still raw from the Boyle and Yablonski episode, I was asked to sing for a UMWA convention. One of the organizers asked me not to sing the song, for some of Boyle’s supporters were going to be there, and they weren’t sure how they would react to the song. But mainly they wanted the opportunity to win their support, so that they could start getting the union back on solid ground again.”

Hazel rose to the occasion, as she always did. Her message was exactly the one that was needed, even if she couldn’t always share it when the wounds were still open. Her song isn’t really about hating Tony Boyle or loving Jock Yablonski. It’s about hating corrupt power – the “trash” that keeps working people down – and it’s about loving, and saving, a union.

Coda

Where does that leave us? “The Yablonski Murder” is indeed a murder ballad proper, but only insofar as it shares the news of such crime. It has little in common with traditional murder ballads beyond that. We’ve used the phrase “political murder ballad” in this blog before, and that is certainly a more appropriate description. Even so, I think we need to carve out a bit of ‘sub-category’ territory here, if it matters. What I mean is this just isn’t a labor movement ‘political murder ballad’ like “1913 Massacre” or “Ludlow Massacre”. It’s for a different time with different, more complicated, problems. Solidarity against the owners and their thugs in a time of class warfare is one thing, but building solidarity after your union has descended into corruption and civil war is quite another.

I intend to spend some time on that earlier tradition of political murder balladry, particularly in the coal fields, next week. “The Yablonski Murder” has only one foot in that tradition, so I think we’ll get more out of looking at it separately. Actually, Hazel did give us a newer song firmly planted in that old tradition, about that disaster I mentioned above, and so we’ll see that next week as well. On the whole though it seems to me that the older labor songs actually borrow much more from traditional Appalachian murder balladry than does our topic song for this post, but you’ll have to judge for yourself to see if I can prove the case in that next post.

For now, it’s worth considering that Jock Yablonski’s murder has often been noted as the last political assassination of the turbulent 1960s. The unions were no more immune to corruption and to the push for reform than any other American institution during that decade. And violence in that context is certainly something we’ve seen in this blog before. In fact, I note with some strange fascination that this is the third murder just from December of 1969 we’ve considered at Murder Ballad Monday. Meredith Hunter’s killing at the Altamont concert and Fred Hampton’s assassination both already appear in our work. “The Yablonski Murder” then might be more appropriately seen as music in the social and political context of the time of its creation than as simply a labor song – ‘category, political murder ballad – sub category, 1960s.’ I don’t know – maybe you’ll just have to figure that one out for yourself.

Thanks for reading and sticking with me this week!

[Editor’s note: For more information on the crime itself, check out The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette archives.]