Vengeance and Loss: Yiddish Songs of the Holocaust, pt. I

Introduction

We have rarely strayed far from English language sources at Murder Ballad Monday. Whether the songs we explore pull from the British Isles or from African-American or Maritime traditions, for example, our idiom has typically been English, and our sources mostly Western European or North American. This is not exactly by design, and we’re eager to broaden out when we can.

As we have been exploring the musical interpretation of violence and mortality over the years, I have been wondering if we would ever encounter music addressing the Holocaust. The musical responses to that mid-20th century horror with which I’m familiar have been mostly classical and instrumental. I haven’t yet encountered original compositions in English that attempt to address it, at least as a type of song we usually explore. It’s not an easy story to tell well or responsibly. If anything can fall into the “there are no words” category of events so sweeping and awful that they surpass the scope of tragedy, it would be this human cataclysm.

When my friend, Alison, alerted me to material recently uncovered by her colleague, Professor Anna Shternshis of the University of Toronto, that included lost folk songs from Holocaust survivors, I needed to learn more. After encountering this trove of lyrics previously thought lost, Shternshis knew these songs had to be heard. She asked singer-songwriter and scholar Psoy Korolenko to help revive the written lyrics into living, breathing songs, telling the story of Ukrainian Jews during World War II. These songs encompassed themes of tragedy and loss, but also revenge and martial valor. Shternshis and Korolenko’s efforts were recently featured on Toronto’s Classical 96.3FM, in an in-studio performance and discussion.

In this post and the next, we’ll talk with Shternshis and Korolenko about this work, and explore the function of music in catastrophic times. In shedding light on a particular time and place in Yiddish culture, we will see how the songs present the Holocaust in an aspect quite different from that normally seen in the Anglophone West.

Interview with Anna Shternshis and Psoy Korolenko (edited and condensed)

MBMonday: Please tell us the story of this archive of songs and how you came across it.

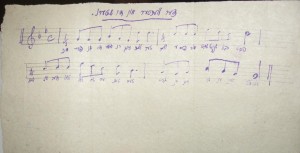

Anna Shternshis: This music is from the Archive of the Kiev Cabinet of the Jewish Proletarian Culture, a small research institute of the Ukrainian Academy of Science. In the 1930s, the Cabinet ran a number of research projects related to the Yiddish language: linguistics, folklore, and ethnomusicology. During World War II, Moisei Beregovsky (1892 – 1961), the chief ethnomusicologist of the Cabinet, ran a number of projects on field-recording Yiddish songs in all areas of the Soviet Union: in Central Asia and Ural mountains where 1.6 million of Jewish refugees survived the War, in 1944 – 1947 in the Soviet Ukraine. During the expeditions, he and his team recorded thousands of Yiddish folksongs, including about a hundred of those that deal with the experiences of the war. Beregovsky planned to publish the book called Jewish Creativity in the Soviet Union during World War II, but he was arrested in 1949, along with most of his colleagues, so the book never appeared.

In 1949, the Cabinet was shut down, and all its researchers were arrested on false charges of espionage. During this time, the Soviet Union shut down all Jewish cultural institutions. Beregovsky spent seven years in jail, as did many of his colleagues. When he was released, in 1956, he received all his notes back, except for the materials from the wartime expeditions. He believed that they had been lost or destroyed, but they had instead been stored in an archive in Ukraine. In the 1990s, the boxes were moved to the manuscript department of the Ukrainian National Library, where they had been cataloged.

I found the documents in the mid-2000s. Upon quick look, I realized that all songs from the collection were previously unknown. They told stories of Soviet Jews from the perspective of the 1940s; and they discussed places, such as death camp/ghetto Pechora, ghettos in Transnistria areas of Ukraine, and other places. Some songs were written in the trenches by Jewish Red Army soldiers. Others described Jewish life in the Soviet Central Asia. Historians did not know that survivors and victims from these places left any materials behind, and the collection opened, as a result, an entirely new dimension of Holocaust history, culture, and music.

Immediately after I found the materials, I got in touch with Dr. Pavel Lion, better known under his stage name Psoy Korolenko, and invited him to work together on bringing these songs to their audience as art. It took us a year to select about 30 songs, which became the foundation of the project.