Twinkle, twinkle, little star…

Notation of “Duncan and Brady” from Lomax and Lomax, Our Singing Country.

This is the second part of a three part series. See also Part 1 and Part 3.

Introduction

In my first post this week, I introduced the bad man ballad “Duncan and Brady” and explored the historical origin of the song. We saw, based on extensive scholarship, that the murder of patrolman James Brady by Harry Duncan in Charles Starkes’s saloon, near 11th and Christy in old St. Louis on October 6, 1890, is certainly the incident that inspired this ballad. We’ll see with equal clarity today and in the last post of the week that the details of that historical event are almost irrelevant to the narrative of the song, in any version we can find. If you’re looking for the historical inspiration, start with that first post. But if music is what you’re after, stick around. We’ll look at older versions today, and in the last post we’ll see what happened with this ballad during and since the Folk Revival.

Let’s start with the standard ballad cataloging business. “Duncan and Brady” is most often cited by G. Malcolm Laws’ designation ‘Laws I9’. According to the Roud Folksong Index, it is ‘Roud #4177’ and is listed with over four dozen citations. There are dozens of modern versions of this ballad, in several different styles.

So, how did a really bad day in an 11th Street saloon turn into the fictional and fun ballad people love to sing today? Is the answer the same for the other related St. Louis bad man ballads we mentioned in the first post – “Frankie and Albert” and “Stagger Lee“?

“Twinkle, twinkle, little star…” Origins: Musical (and not so factual)

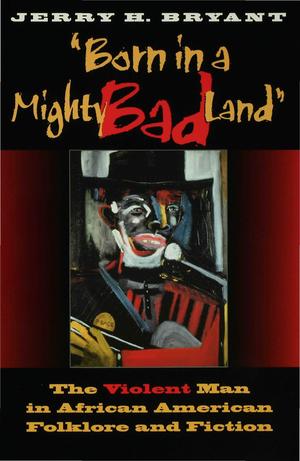

Jerry H. Bryant, emeritus professor of English at California State University, in Chapter 2 of his “Born in a Mighty Bad Land”: The Violent Man in African American Folklore and Fiction, outlines the historical conditions that created real life ‘bad men’ in post-bellum African-American communities. It’s a fascinating read, but it doesn’t help much with our questions insofar as such conditions existed in many communities other than St. Louis. So what was it about these few blocks in St. Louis in the early 1890s?

Jerry H. Bryant, emeritus professor of English at California State University, in Chapter 2 of his “Born in a Mighty Bad Land”: The Violent Man in African American Folklore and Fiction, outlines the historical conditions that created real life ‘bad men’ in post-bellum African-American communities. It’s a fascinating read, but it doesn’t help much with our questions insofar as such conditions existed in many communities other than St. Louis. So what was it about these few blocks in St. Louis in the early 1890s?

We can’t know precisely why at least three of the most enduring bad man ballad prototypes (according to Bryant’s classification system) seem to have come from one small part of St. Louis in less than one decade. Evidence suggests all but surely that there was no common author. But we do know from all sorts of research that these ballads appeared at a time of intense musical creativity throughout the South, in both black and white communities. There’s no real mystery about all *that*.

The ‘folk process’ dial was ‘turned up to eleven.’ Black St. Louis was undeniably a place where such musical creativity was most fully ‘amped up’. Any spark of a song there and then had a chance of arcing out and blazing into a greater world beyond the city’s docks and levees. These stories must have made for great fun and entertainment wherever they traveled then, as they do now. Of course, without recordings to pass along lyrics and tunes, the sharing had to be done by means of oral tradition and live performance.

Unfortunately, and probably for some of the same reasons, we have yet to find any definitive 19th century primary sources that can enlighten us as to exactly how and when the sad news of October 6, 1890 turned into such an effective bit of upbeat entertainment. We do, however, have a few tantalizing bits and pieces from that century that at least suggest some answers. All are cited by John Russell David in his 1976 PhD thesis Tragedy in Ragtime: Black Folktales from St. Louis. (I apologize if I take too much time with them for your purposes here, but each really matters if you want to know the deepest roots of the song. If you want to hear music, head down the page to the first recorded version by Wilmer Watts and start there.)

1. Starkes’ Brutal Song – On January 19, 1891, just over three months after the murder, the St. Louis Post Dispatch published a story titled “Stark’s Brutal Song”. The paper reported that two officers had been on routine foot patrol near Charles Starkes’s saloon, and on nearing the bar door witnessed Starkes and three other men exiting the establishment singing…

Officer Brady is dead and gone

Officer Gaffney has lost his gun

We will now have lots of fun

in Charley Stark’s saloon.

According to David, “when Starkes saw the officers, he made a break and the police gave chase. Starkes denied singing the song and claimed that he and his friends were singing verses from “John Brown’s Body”.” The two officers swore that Starkes and the others were singing “in a boastful manner.” It’s also worth noting that, in contrast to later “Brady” songs, every part of this little verse is historically accurate (even the last two lines, I’m sure.)

David also found, in a book about famous crimes of St. Louis, evidence of a lyric taunt that black citizens used against police officers on the streets of east St. Louis in the weeks after the murder.

Brady’s dead and Gaffney’s down,

We’ll get busy in this town.

Chase the policemen off the beat,

chase the white folks off the street.

Is ‘Stark’s Brutal Song’ a scrap of the original “Duncan and Brady”? Maybe. The meter is right, more or less, though that doesn’t prove anything. We can say the same of the taunt. Of course, without the music, there’s really no way to know. However, whatever these scraps were, they do lead to a couple of reasonable conclusions.

First, we can state definitively that people were singing and rhyming about Brady’s murder less than four months after it happened. If either of these fragments isn’t a part of it, it’s not a stretch to posit that the original “Brady” ballad probably emerged that quickly as well. It’s quite possible in fact that the “Brady” proto-ballad was actually an aggregation of several such rhymes and taunts, coalescing after several weeks or months of diverse and spontaneous lyric improvisation. The streets were full of people who could create such lyric riffs, and the St. Louis saloons and bordellos were full of musicians who were masters at making structure from such improvisational scraps. In a very real sense then, we are perhaps looking at pieces of the ballad’s lyric DNA.

Second, these particular verses about Brady’s murder are very much about black citizens getting the best of white police, many of whom were Irish like Brady. Indeed, tensions between Irish folks and black folks developed into a pitched race riot in the spring after Brady’s murder, in great part because of the fallout from the events surrounding the crime. There can little doubt then that, even if these scraps aren’t part of the original, this taunting and bragging is the proper tone of whatever song became “Brady and Duncan.”

In other words, “Duncan and Brady” is both violent and fun today because it was *written to be violent and fun* from the beginning, because it was fun to sing about the Irish cops losing and the black citizens winning. This wasn’t a lyric news story or a tragic song that became something else more upbeat. The historical details were secondary to that cocky attitude of resistance that is and was the keen edge of the ballad. No doubt, the ragtime piano keys of east St. Louis were the whetstone.

2. W.C. Handy, 1893 – David also cites W.C. Handy’s Father of the Blues, An Autobiography as one of his sources. Presumably in that work he discovered the story of Handy’s visit to St. Louis in 1893. Handy recalled the name of a popular ragtime tune he heard during that visit – “Brady, He’s Dead and Gone.” David believes this was certainly what we now know as “Duncan and Brady”. Whether it was or not, if Handy’s memory was reliable, it again shows that the murder of Brady was very much the stuff of local musical entertainment even before Harry Duncan would hang for the crime. There can be little doubt that “Duncan and Brady” is a song of the very early 1890’s.

“Robert Winslow Gordon, first head of the Archive of American Folk-Song, at the Library of Congress, with part of the cylinder collection and recording machinery, about 1930.” Library of Congress

3. Story reported to Robert W. Gordon, ca. 1893 – David as well digs in to all of the sources I cite below (and more.) His investigation of what you’ll see is Version B from The American Songbag, published by Carl Sandburg in 1927, took him to Robert Winslow Gordon’s ground-breaking work and massive collection. Gordon over the years collected several accounts of individuals recalling the experience of hearing “Duncan and Brady”, from Delaware and Virginia to the Desert Southwest. One letter reveals a truly enlightening story. E. D. Baker wrote to Gordon on April 14, 1924, responding to Gordon’s request for information and lyrics connected to “Duncan and Brady”. (I’ve left Baker’s misspellings as is.)

“You ask for a version of a song intitled ‘King Brady’…. I don’t remember just what the verses were that you published, but I can give you a few that I remember hearing sung by Negroes, and it was composed by Negroes, each one of them writing a verse to suit himself, as there is no limit to them, for I have heard one of them sing for an hour, at least, on the song, and not sing the same verse twise.

The song is not intitled ‘King Brady’, just ‘Brady.’ Brady was Cheif of Polease in East St. Louis, and was shot and killed by a Negro gambler, named Duncan. Brady was very strict with the sporting element, especially the girls of the restricted distric, who he would not allow to come down town dressed in red…. Brady must of wore a Stetson hat for it is mentioned in the song quite frequently like one verse windes up ‘Brady, Brady where you at? Strutting in Hell with his Stetson hat.’ He must of been killed some time in the early ’90’s, as I heard the song in the Spring of ’93.”

Not only does this give us a third independent piece of evidence that there was singing on the topic soon after Brady’s murder, the reference here almost certainly identifies this version as what would become “Brady and Duncan”. Unfortunately, it’s not clear to me from the research I’ve found if any of these alternate verses Baker references to share in supplement to Gordon’s published version (Sandburg’s Version B, it would seem) survive.

Moreover, this is a stunningly clear example of common black folks as highly skilled integrators, in Long-Wilgus’s terminology. In other words, the folk process was clearly on display for Mr. Baker, but we can say more. There can be no doubt that the great variety we see in the ballad is in no small part due to the reflexive artistic craft that black folks cultivated as an essential survival tool in a society built on white supremacy. Each man “writing a verse to suit himself”, presumably during some labor Baker was witnessing, is essentially “each man finding his own way to survive one more day with his spirit intact.” And every new creation, every new verse that someone improvised to make it through one more day of a hard life, had at least a chance of coming on down to us. We’re lucky that so many did.

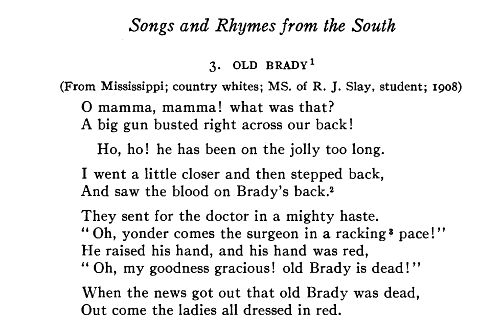

4. “Old Brady” 1908 – Finally, from the early 20th century we have an article by E.C. Perrow titled “Song and Rhymes from the South“ for The Journal of American Folklore, from the Spring of 1912. The author had moved to East Tennessee as a child, and was beginning publication of “a collection of such fragments of popular verse as I could remember or could induce my friends to write down for me.” In his ‘outlaws’ section, we find an early version of “Duncan and Brady”. Though still fragmentary, there is more unique material and yet another revelation.

The lyrics, of course, are curious, as we see “been on the jolly too long” as a likely relative of “been on the job too long.” We see other elements common to the modern versions as well – the doctor’s examination of Brady, and the ‘ladies’ dressed in red. Perrow’s identification of Brady as an outlaw killed in Mississippi is not surprising, as folk songs often take on local identity and characteristics as they move.

However, it’s his note at the top that allows us to at least say one more thing for sure. This version was collected from “country whites”. If that and the other details of the provenance are true, then we can declare with certainty that “Brady” had made the jump from black to white singers at least as early as 1908. Certainly it was still circulating among black folks too, as Howard Odum published a sample in 1911 that he collected from African-American sources. Perrow though identifies it as an outlaw song, in the same vein as “Jesse James”. That’s not hard to see, and it certainly helps explain how a song that was, at least in part, a statement of black racial defiance in the early 1890’s could so easily translate to rural whites. Who doesn’t root for the outlaw in a good folk song?

“The Devil says ‘Where you from?’ ‘East St. Louis!'” – The 1920s

The earliest complete documentary evidence we have thus far of “Duncan and Brady” dates only to the 1920’s, thirty years after the probable writing of the proto-ballad. I have two textual sources and one sound recording to share from that decade, and they’re much of what can be easily found.

-Sandburg

Carl Sandburg offers two texts of “Brady” in his 1927 American Songbag. He writes:

“A Nebraska-born woman, now practicing law in Chicago, gives us one verse and a tune from St. Louis. It is a tale of wicked people, a bad man so bad that even after death he went “struttin’ in hell with his Stetson hat.” Geraldine Smith, attorney at law in Chicago, heard it from Omaha railroad men. It is Text A. Then from the R.W. Gordon collection we have Text B. The snarl of the underworld, the hazards of those street corners and alleys ‘where any moment may be your next,’ are in the brawling of this Brady reminiscence.”

Sandburg’s texts A and B are transcribed here. Text A is interesting in that, besides reversing the main characters’ names, it locates the saloon in question at 12th and Carr, a few blocks away from the actual site of Starkes’ saloon. It’s a direct reference to East St. Louis though! Text B, mentioned above in relation to E.D. Baker’s letter to Gordon, intrigues me because it seems to preserve at least one key element of the true story that we saw in the first post – that Harry Duncan was with his brother when the shooting happened. Did the original version of the ballad include this fact as well?

Generally, both have some lyric connections to the later versions we’ll get to know, but both also seem to have unique elements no longer present. Given the dates of Sandburg’s collecting, both are likely closer to the original ballad than anything available commercially today. But given the provenance he describes, and the obvious difference between the two, I also don’t see solid evidence that either is a pure version of that mysterious original.

-Scarborough

A text from 1925 by Dorothy Scarborough called On the Trail of Negro Folk Songs also cites fragments of the ballad, provided her by two white Texas women with some interest in the collection of African-American folk songs. The entry with her examples is worth reading (see it here) though not particularly because it provides much in the way of enlightenment regarding the ballad. Indeed, the casual racism expressed by one of Scarborough’s ‘collectors’ is such a clear barrier to her objectivity that one is inclined to dismiss the whole mess! Certainly such sources do not represent the height of folk song collection.

However, when we put all that in the background as we must in due diligence to get to the content, we meet the same situation we did with Sandburg. Some of the lyric elements are unknown in modern versions, and some are similar or identical. Most notably, the opening line of “Twinkle, twinkle, little star” appears in two of Scarborough’s examples, and so this most common opening in modern versions clearly has roots that stretch back at least to the 1920s. On the other hand, the provenance of all being reportedly of Texas, these fragments almost surely do not represent the unaltered St. Louis original.

Indeed, between Sandburg and Scarborough we see at least five divergent variants, collected from Omaha to Houston. That proves nothing grand. We can say though that, before 1930, this ballad was already spreading along the Mississippi and the Gulf, and that it was going through the folk process just as we’d expect in such travels. They all *seem to be* from African-American sources, but even the evidence for that is not wholly conclusive, particularly in Sandburg’s case.

– Wilmer Watts and the Lonely Eagles

We are lucky enough to have *one* early recorded version, cut in North Carolina in 1929, far from the Mississippi. It is the oldest known sound recording of the ballad. “Been on the Job Too Long”, by Wilmer Watts and the Lonely Eagles, does support our earlier conclusion about the ballad – if it hadn’t happened by 1908 as Perrow’s scrap suggests, then most certainly by the 1920’s “Brady” had made the jump from black to white musicians. (See the last entry on this page for a lengthy biography of Watts.)

Lyrics for Wilmer Watts’ version

This example is most intriguing. Here we see again the “Twinkle, twinkle” opening line which is common today. But in this variant, Brady is a rough and tumble worker on the telephone line, and Duncan is a mean cop. Whether this reflected something specific to rural North Carolina in the ’20s is hard to know, but it’s a curious variation. As well, as in one of Sandburg’s versions, there is a trip to hell for Brady in this one! Again, one wonders if this is a remnant of the older ballad that eventually dropped off.

Another curious element is that “both white and black” gather for Brady’s funeral. Of course, whether this is some older part of the ballad from St. Louis or is something Watts or his source added can’t be known without more evidence. We do know that, according to the St. Louis Dispatch, Harry Duncan’s actual funeral after his execution for the murder of Officer Brady was well-attended by “all classes of individuals, white and colored, male and female, young and old.” The lyric could be an echo of the actual event, and thus perhaps of the proto-ballad.

Interestingly, his biography suggests that Watts might have been one of those young white southern men we’ve discussed before, a man perhaps like Dock Boggs, who was an avid student of music regardless of his teacher’s skin color. Patrick Huber, the scholar who wrote the biographies linked above, claims based on family stories that one of the Lonely Eagles who worked at the mill with Watts, Charles Freshour, learned to play guitar at age nine from a local black street musician.

Without more background though, the significance of that lyric is unclear. We can at least feel comfortable in observing that performing a lyric like that in a southern white string band suggests singers and pickers with minds more flexible than that of the woman who provided songs for Dorothy Scarborough!

As for the recording’s musical influence, check out this modern rendition of Watts’ version by Rhonda Vincent for a start.

“You’ve got me best!” – African-American Sources from the 30’s and 40’s

Not surprisingly, John Lomax and Alan Lomax and their assistants provide the earliest examples of sound recordings of African-American performances of “Duncan and Brady.” We see in the Library of Congress several catalog citations; one for a recording from a prison work crew at Parchman in Mississippi in 1933, as well as others for recordings of other black musicians such as this this one of Arthur “Brother in Law” Armstrong from Texas in 1940 and this one of Will Starks from Mississippi in 1942. Unfortunately, I don’t have pockets deep enough to pay the LOC to digitize these!

The Lomaxes did publish, in their 1941 collection Our Singing Country, a partial transcription of the lyrics to that 1933 performance by the convicts at Parchman Farm. Ruth Seeger’s musical notation from the same publication is at the top of this blog entry.

Here is the transcription of that performance, with additional collected verses added by the editors in a dubious attempt to, as they say, “tell the story again the way the original may have told it.” Also included are their notes regarding the song.

We also have later recordings of performances by Alan Lomax, linked here and here, which probably reflect a good deal of the original lyrics and tune of this ballad as he heard them – though they certainly can’t be considered perfectly reliable reproductions.

However, we do have a critical, classic recording of the ballad by John and Allen’s greatest ‘folk discovery’, Huddie Ledbetter. Lead Belly’s 1947 version uses the same tune as Lomax in his performances, and Lead Belly’s lyrics are quite close to those in Our Singing Country. It’s possible of course that John or Alan added verses to that transcription they learned directly from Lead Belly’s singing, as they both knew him and his music quite well years before the publication of Our Singing Country in 1941. The close correlation then might not be indicative of much more than that relationship. Still, we know by comparison with other recordings that many of Lead Belly’s performances serve as reasonably reliable examples of ballads in the southern prison system during the Great Depression. There is no reason to doubt that such is not true with “Duncan and Brady”.

Even without hearing the original recordings in the LOC, we can be equally suggestive that the tune, quite different than Watts’ or any you’ll hear in later versions, is representative of the African-American strand of the ballad there and then as well. You’ll probably recognize the tune as “Little Sadie”, but we’ll get to all that in a minute. For now, check it out. You can use the Lomax lyrics link again for reference.

We may not be able to draw grand conclusions from all this, but that “Little Sadie” tune is certainly more than just a random creative choice of Lead Belly’s applied to this ballad. We know that the tune was very much a part of the bad man ballad tradition – in fact, here’s a recording by the Lomax team of Willie Rayford (a prisoner at Cummins State Farm in Arkansas, see these field notes) singing nothing other than “Bad Man Ballad”, aka “Bad Lee Brown” and “Little Sadie” (Laws I8). (Note, the citation says the recording date is 1939 but Lomax’s field notes put it as 1933.)

It’s reasonable to assume at least that this was one standard tune for “Duncan and Brady” for black men in the prison system in the deep south at that time. Whether or not it’s the original tune from St. Louis can’t as yet be known, though several other reasonable assumptions argue against that probability.

The lyrics are interesting as well. Leadbelly sings of Duncan’s “grocery” more often than his saloon, and a reader’s comment at Mudcat sheds some light on why there may have been less difference between the two in the 19th century than we might expect. And, as we saw above, we see here multiple elements that are clearly present in most of today’s versions as well as several that are now left out. It is just as hard here to speculate intelligently about which, if any, of these elements can be traced back to the original and which are later additions. Certainly anything that was present in the ballad as far back as the late ’20s or early ’30’s is a candidate for being part of the original, whether it lasts through to today or not. Just as certainly, such a presence is not evidence of connection to the original.

John Lomax felt qualified to make such claims and painted Lead Belly’s southern prison version as likely being closest to the ballad prototype. But we just can’t safely say that – truly, the question is still open. There is just too much time and geography between Morgan Street in 1890 and Parchman Farm in 1933. That distance is even metaphorically greater given that widespread recording and playback technology was not available during more than half of that period. Creativity and poetic licence undoubtedly trumped fidelity as the ballad spread in the interim. The only thing I’ll say definitively is that we’re lucky Lomax was able to capture such audio snapshots when he did.

Coda

So, we can’t know the original ballad with the evidence we have now, but we’ve at least gotten a glimpse of it in the 19th century and a more detailed look at this ballad from the 1920s to the 1940s. All that’s left really now is to take a nice stroll through the rough alleys and two bit saloons that this ballad has frequented since then.

My own Spotify playlist below so far includes versions from 34 separate artists, and my Youtube playlist includes a few more that aren’t available on Spotify. You can jump there right now if you just can’t wait for a curated look! Otherwise, I hope you’ll come back later this week for that music-filled post.

Until then, thanks for reading!