The wind will blow it higher: “Biko”

“The man is dead, the man is dead”

This week marks the 40th anniversary of the death of South African anti-apartheid activist Bantu Stephen Biko. Biko, a leader in the Black Consciousness Movement, died in the custody of South African security services. A banning order imposed by the government in 1973 for his organizing activities had prohibited him from leaving the district where he lived, meeting with more than one person at a time, speaking in public, or belonging to a political organization. It also prohibited the media from quoting him. The police stopped Biko at a roadblock on August 18, 1977, and arrested him for violating the travel ban.

Security services detained Biko in two facilities in Port Elizabeth, South Africa. They subjected him to various forms of mistreatment and physical abuse. On September 6, 1977, a 22-hour interrogation at the second facility involved physical abuse that left Biko critically injured. The abusive confinement and medical neglect continued until a doctor recommended a transfer to a hospital on September 11. Rather than taking Biko to the nearest hospital, the security services loaded him into the back of a Land Rover, and drove him over 740 miles (1100 km) to a prison hospital in Pretoria. He died in a cell there on September 12. He was 30 years old. (View the Steve Biko Foundation’s exhibit on Biko’s final days here.)

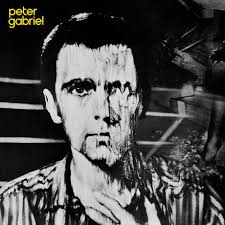

Three years later, on May 22 1980, Peter Gabriel released “Biko” as the concluding track of his third, untitled album, informally subtitled Melt. “Biko” was not the first song to protest Biko’s killing by the state. It would not be the last. It became, however, the most widely-known, and probably the most influential. Indeed, “Biko” is a strong contender for the title of most significant protest song of the 1980s in the Anglophone world.

Three years later, on May 22 1980, Peter Gabriel released “Biko” as the concluding track of his third, untitled album, informally subtitled Melt. “Biko” was not the first song to protest Biko’s killing by the state. It would not be the last. It became, however, the most widely-known, and probably the most influential. Indeed, “Biko” is a strong contender for the title of most significant protest song of the 1980s in the Anglophone world.

As we explore the story of the song, we’ll discuss Gabriel’s own ambivalence about his credibility in this protest. We’ll see how his live performances of “Biko” engage art and activism. We’ll assess the song’s musical influence as well as its political influence. “Biko” will inspire and cultivate new directions for popular music, and be embraced by other artists. We’ll conclude with a brief tour through other songs mobilizing the memory of Steven Biko in opposition to the forces that claimed his life, both apartheid specifically and racial oppression generally.

Before we proceed, I want to add one caveat to avoid misunderstanding. In making the case for the significance of “Biko,” and the influence of it and other songs, I understand that that significance depends on the work and sacrifice of Steve Biko in particular and thousands of others engaged directly in the struggle for human rights and against apartheid. Gabriel was conscious that his song was an outsider’s song, and we will be, too. Our focus here is mostly on the story of songs and less on the stories behind them. The story of “Biko” (the song), is one where music helped elevate a martyr. It enlisted allies in the world outside of South Africa to apply pressure to assist those working within South Africa. No outsider song could possibly do enough, but no outsider song did more than “Biko.”

Sound and sense

The genesis of “Biko” involves two themes that develop over the course of the song’s career, and Gabriel’s—growing international attention to human rights abuses, and a growing audience for “world music.” Gabriel biographer Daryl Easlea explains in Without Frontiers: The Life and Music of Peter Gabriel, that Gabriel was part of a community that had been paying attention to Biko’s detention:

“Gabriel had noted in his diary the death of student activist Steven [sic] Biko at the hands of the South African police in September 1977… Like many white liberals with an awareness of events in South Africa, Gabriel was shocked by the brutality and the subsequent cover-up by police, and decided to capture his thoughts in song.”

Gabriel acknowledged in 1987 that Biko’s story was not widely known at the time he wrote the song. He felt that the story of one individual’s suffering would be compelling for audiences previously uninterested in the ongoing conflict. Biko was in many respects a sympathetic choice. He was young, nonviolent, and he had no association with international Communism. He was not a member of the African National Congress (ANC). Furthermore, he had engaged in no criminal activity or violence, and been convicted of no crime. He was arrested only for violating a ban that was itself a clear human rights violation.