The Banks of the Ohio — Part One

|

| “By her lily white hand (Banks of the Ohio),” by Julyan Davis, 2012 |

Take a little walk with me…

“(Down by the) Banks of the Ohio” is a favorite murder ballad for many. It is not one of mine.

I admit that this a challenging place to begin. I may have trouble building interest from there. We generally stick with songs that we’re most passionate about, or ones that present interesting questions or issues. If I can’t deliver on the former, I hope to deliver on the latter.

If I’m reluctant to launch into this song, it’s partly because it doesn’t give us anything especially new in the tradition of riverside sweetheart murder ballads–new in and of itself, or new to us after several years of blogging. We’ve already been to that metaphorical riverside before…several times. Perhaps we should have come to “Banks” earlier.

If you had to strip down a riverside sweetheart murder ballad to its essence, you would get something very much like “The Banks of the Ohio.” Not much in the way of frills or hooks here. Unlike “Omie Wise,” there’s no one, real, historical incident from which we can take our bearings. Unlike “Down in the Willow Garden,” there’s little evidence of a more ancient heritage, and no narrative mystery equal to the father’s bad advice to murder Rose Connelly, or the son’s poignant remorse in facing the gallows while his father cries. Unlike “The False Sir John,” it is not ancient, nor does it contain a surprising reversal, at least in most versions.

Frankly, it’s also musically rather bland. I suspect that part of its popularity with aspiring musicians may be its abundant space for fairly predictable, sometimes plodding bass runs. Fortunately, as we’ll hear along the way, some folks manage to achieve some not so obvious things with their arrangements. This helps; the song has grown on me…just a little.

What I hope to do in this post is to provide some classic performances of this song. In the next post, I’ll explore the particular difficulties that emerge from the song’s theme. I have a theory I’d like to share with you about how the song has related to real life through the 20th century and into the 21st. I also want to explore how these difficulties get addressed, primarily by female performers. What “Banks of the Ohio” gives us is not only perspective on an anxiety-laden transition in American courtship, but also a song that, well on the other side of that transition, women artists, in particular, have creatively manipulated and modified to fit new sensibilities. I’ll have more on that a little bit downstream.

Headwaters

|

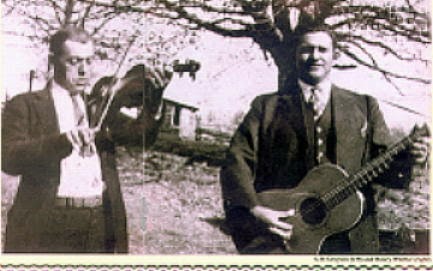

| G.B. Grayson and Henry Whitter |

“Banks of the Ohio” may be a distinctly American variant of “Pretty Polly”/”The Gosport Tragedy.” Some sources allege a 19th century origin, although the earliest date noted by the Traditional Ballad Index is 1915. The song’s author and origin are unknown.

Carl Sandburg doesn’t mention it in The American Songbag in 1927 (although he does include a version of “The False Sir John,” which he labels as “Pretty Polly”). MacEdward Leach doesn’t mention “Banks” in The Ballad Book in 1955. Harry Smith ignores it in his Anthology of American Folk Music. Nevertheless, it’s been fairly widely recorded. Let’s take these two factors together as evidence for it being popular without being especially distinctive.

Whether the song actually originated in the 19th century or the 20th may make a difference for our overall

story, especially in the next post. Regardless of the answer to that question, the first recordings come to us from the late 1920s.

G.B. Grayson and Henry Whitter recorded the song in 1927 as “I’ll Never Be Yours,” which you can listen to at the Internet Archive here.

Red Patterson’s Piedmont Log Rollers recorded a version in 1927 or 1928 (sources differ).

Bill and Charlie Monroe recorded the song together in 1936, before Bill Monroe went on to define Bluegrass with his own band.

Listen on YouTube here.

Monroe also performed the song with Doc Watson, in a performance captured on Smithsonian Folkways’ recording of their performance at the Ash Grove in Los Angeles in 1963.

Listen on YouTube here.

Watson recorded the song several times, including with his son, Merle, and performed it innumerable times, including in this “Three Pickers” supergroup performance with Ricky Skaggs, Alison Krauss, and Earl Scruggs.

Last, but not least–an in some ways, not last– I wanted to make sure to include this intimate live recording of the song from the Alan Lomax Archive. Watson plays the song with Clarence Ashley on lead vocals. We posted this clip sometime back on our Facebook page, and received an uncommonly warm response.

“Banks of the Ohio” has abundant highly qualified interpreters, especially within the Bluegrass and Old Time traditions. I’ll include a Spotify playlist below so that you can explore them more fully. It includes performances by Bascom Lamar Lunsford, The Blue Sky Boys, The Country Gentlemen (Spotify) and others. Johnny Cash recorded the song with members of the Carter Family and later on in the recordings he made in his last decade.

I won’t give a comprehensive catalog of performances here, in part for the sake of brevity, but mostly because most of the mainstream performances by male artists don’t differ much or vary from the basics. Some are musically better than others, but few present something new or any obvious measure of “folk process.” I’ll need to beg your leave to continue into a next post. When we resume, I will look at how our ears for the song may differ from when it first emerged, and also listen for the way in which women performers have taken up the narrative. For my money, that’s where things get truly interesting. Stay tuned.