The Ballad of Laura Foster

|

| Not Laura Foster |

This is the fifth post in a series on “Tom Dooley” and related songs. The first post discusses some of the facts behind the story that inspired the song. The following three posts “Hang down your head, Tom Dooley,” “You can take down my old violin,” and “Poor boy, you’re bound to die,” discuss the history of the most popular of the “Dooley” songs.

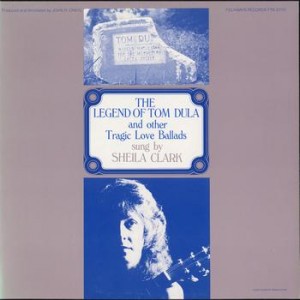

Sheila Clark and The Legend of Tom Dula

Smithsonian Folkways released The Legend of Tom Dula and Other Tragic Love Ballads by Sheila Clark in 1986. The album contains each of the three “original” Tom Dula ballads, a Dula ballad of Clark’s own devising, and a B-side comprising a number of other thematically related ballads. It’s the one audio recording I can find of the poem by Thomas Land, which is listed by Clark as “The Ballad of Laura Foster,” and by The Frank C. Brown Collection of North Carolina Folklore as “The Murder of Laura Foster.” In today’s post, we’ll explore Clark’s album and we’ll discuss how some of its Tom Dula songs as well as some other, more recent musical re-tellings continue to change the details to improve the story.

side and her choices of traditional ballads on the second make for a thorough exploration of some core themes. Among the tracks on the second side are ones we’ve listened to here before, including “House Carpenter” and “Silver Dagger.” They’re all, in their own ways, songs of heartbreak and potentially deadly seduction. We’ve come across a few murder ballad only albums, leading of course with Nick Cave‘s, but also catching a few tracks off of Mark Erelli and Jeffrey Foucault’s Seven Curses. There are other excellent collections to be sure, but I’m impressed with Clark’s work as being more than simply a collection of murder ballads. Clark’s album pulls out the nuances of a more defined set of themes, and the later songs make the earlier ones more effective.

I hope to get to a discussion of an example of an album-length murder ballad in a couple weeks. Clark’s effort is close to it. Incidentally, I’m a little perplexed that I can’t find additional material by Clark or any biographical information about her, even on the liner notes from Folkways. If any of you can help supply this, I’d be grateful for your comments.

The North Carolina Ballads

The lyrics for this performance and all of Clark’s songs on this album can be found here. Apologies to all of you not able to listen to the Spotify tracks. You can hear shorter samples on the Smithsonian Folkways site here.

The full lyrics to the version as printed in The Frank C. Brown Collection of North Carolina Folklore are at the end of this post. I’ll pull out a few up here to note a few key differences in how this song tells the story, which illustrate that “making the story better” happens in a number of different ways.

First, Land’s poem deploys several verses to cast Laura as a truly innocent victim on this, heightening the tragedy. While I’m firmly convinced that she in no way deserved her fate and with no criticism intended of her character, the charitable depictions of Laura’s virtue are likely there more for dramatic effect than for the sake of historical accuracy.

Her youthful heart no sorrow knew;

She fancied all mankind was true,

And thus she gaily passed along

Humming at times a favorite song.

Land’s poem also goes into far greater detail about the case than any of the the three North Carolina ballads

and clearly alleges a conspiracy. The song mentions neither Tom Dula nor Ann Melton by name, but leaves no question that the murder was the work of more than one.

As eve declined toward the West,

She met her groom and his vile guest.

In forest wild the three retreat;

She looked for person there to meet.

Even in accounting for the trial, the song doesn’t specify who is actually guilty. Land doesn’t let the legal finding distract him from the poetic one.

The jury made the verdict plain :

‘Twas that poor Laura had been slain;

Some ruthless friend had struck the blow

That laid poor Laura Foster low.

Paul Slade, in his article on the “Tom Dooley,” points out that Land’s piece was probably not meant to be sung, and it’s clear from Clark’s performance of it that the proper meter is sometimes lacking. She does a fine job with the song as it is, and it’s ultimately the weight of verse after verse that helps impress the sadness of the song on the listener. It’s not as lively as “Tom Dooley.” Land’s moves, both to tell the story more fully, but also to hide or remake certain details, provide further examples of the artist’s work to make history “better.”

The last of the three original North Carolina Tom Dula ballads included on Clark’s collection is “Tom Dula’s Own Ballad.” Brown’s collection cites Mrs. Maude Sutton again in claiming that this song was actually written by Dula.

“Dula was again convicted and sentenced to die on May 1, 1868. His friends brought his banjo to him in Statesville and he composed and sang the ballad about his banjo and the murder. It is in the same spirit as that in which MacPherson, Burns’s hero, ‘Sae wantonly, sae dauntonly’ sang ‘beneath the gallows tree.”

The Brown collection notes that attribution of the song to Dula’s authorship is not supported by newspaper accounts of the trial in the New York Herald. The MacPherson tie and the dubiousness of the claim about Dula’s songwriting raise for me two key principles of “Tom Dooley” scholarship. The first is that there are few completely new theories about the story or the song. The second is that almost every detail of the case has been fouled up or misrepresented by somebody, somewhere, and that when they did, somebody else surely repeated it. With this, my fifth post on the song, I’m sure I’ve created an example somewhere.

In any event, the “Tom Dula’s Own Ballad” or “Tom Dula’s Lament” is in its own way a poignant, first-person companion piece to the other songs, and makes use of the same banjo tune as the more famous version.

With that third piece, we now have an account of the three main musical accounts of the Dula/Foster affair emerging from North Carolina. One of them is famous, and the other two much less so. All three of them not only demonstrate many of the ambiguities around the case and the incredible complexity of the folklore that emerged around it, but also the songwriter and storyteller’s craft in managing the details of the historical event to making better stories.

Renovations and rehabilitations

Continuing the effort to set the story straight musically, two more recent singer songwriters have attempted their own takes on the Dula/Foster story.

The first, “The Ballad of Laura Foster,” by Chip Mergott on his 2012 album I Love to Tell the Story, casts Laura as the neglected party in the stories that are told about her murder. This is much more a contemporary singer-songwriter ballad than anything traditional, and Mergott’s poetic license is clearly more than just a learner’s permit. I’m not quite sure what to make of the song’s protagonist’s attachment to Laura. It strikes me as a peculiar artistic stance to adopt. Not that I’m averse to sympathy here, but…

“Laura Foster” by John Lowell provides another variation to the tale. In some respects, it sets the story “straight” not only by incorporating Ann Melton’s involvement rather explicitly. If, as I’ve suggested here and there along the way, “Tom Dooley” succeeds because it successfully plants the suspicion that Tom’s guilt is not what it appears to be, Lowell’s song starts from the other side, and places the guilt with Ann Melton. In part, this draws from folklore around her supposed deathbed confession.

While it’s a different approach, and perhaps gets part of Melton’s role right, this song has its share of fibs to improve the story as well. See if you can spot them.

The lyrics for John Lowell’s “Laura Foster” are here. Putting aside the fact that it might just be even money which one of them, Tom Dula or Ann Melton, did it, a few other issues arise. Lowell, as with everyone else, fails to find a rhyme for “The Pock.” In other words, the theme is romantic rivalry or jealousy, not revenge for transmitting a sexually transmitted infection. I just don’t see any songwriter wanting to attempt that narrative hurdle. I also haven’t encountered any evidence that Melton ever directly implicated Dula, as the song suggests. She never testified in his trial. There are a few other fudges, but I’ll leave them alone, and invite you to consider whether the tone of this song does more justice to Tom Dula or Laura Foster than the originals.

To wrap things up for our discussion of the songs, and to be clear about my point, I don’t have any great objection to the historical inaccuracies in the songs. They do what the songs need to do, which is facilitate the feelings around the story they tell and the themes they contain. I do get frustrated with inaccuracies in the histories, but that’s probably only a vestige of the effort I put in to trying to get the story figured out in the first place. I don’t want to be so relativistic as to say that the real facts don’t matter. They do. But I think it may be more useful or interesting to acknowledge the ambiguities, the mysteries, and the outright falsehoods, and try to understand why they emerged in the first place.

|

| Michael Landon in “The Legend of Tom Dooley” |

Coda: Film and Fiction

I won’t let this fortnight with the Dula/Foster saga go without a quick reference to a couple of other imaginative works built around the story–whether tightly or loosely is obvious in one case and up to you to judge in the other.

The first is the 1958 Michael Landon film, The Legend of Tom Dooley. Landon plays the lead character, whose fate is pretty much sealed in the opening scenes when he kills some soldiers after Civil War, unbeknownst to him, had ended. There is also a Laura Foster, who also faces a tragic fate, but the similarities end rather quickly. As much as music wanted to clean up the story, Hollywood really wanted to put it in a different realm.

Finally, I mentioned Sharyn McCrumb’s historical novel, The Ballad of Tom Dooley, in an earlier post. If you’re looking for something other than the songs or somewhat dryer, true-crime books excavating the facts, McCrumb’s book is a good start. Told from the perspectives of Dula’s defense attorney Zebulon Vance, and Ann Melton’s cousin and servant, Pauline Foster, the novel pieces together the bits of known evidence into a worthwhile and generally plausible literary and psychologically-informed narrative thesis about what really happened. As McCrumb describes it, the story becomes an Appalachian Wuthering Heights. Some of the historians disagree with her theories, but McCrumb contends they are entirely consistent with the available evidence.

With that, and the Thomas Land verses below, I’ll leave off “Tom Dooley” for now. There have been a number of roads not taken, including foreign versions of the song. The story has other artistic outlets as well, including regional theater works. Our two weeks with “Tom Dooley” have drawn significant interest from readers, and the power of the story and the song, and its enduring popularity, will doubtless bring us back again. I’ve started a Spotify playlist incorporating the songs we’ve featured this week and many we weren’t able to get to. Thanks for reading.

The Ballad of Laura Foster

A tragedy I now relate.

‘Tis of poor Laura Foster’s fate —

How by a fickle lover she

Was hurried to eternity.

On Thursday morn at early dawn,

To meet her doom she hurried on,

When soon she thought a bride to be,

Which filled her heart with ecstasy.

Her youthful heart no sorrow knew;

She fancied all mankind was true,

And thus she gaily passed along

Humming at times a favorite song.

As eve declined toward the West,

She met her groom and his vile guest.

In forest wild the three retreat;

She looked for person there to meet.

Soon night came on, with darkness drear.

But while poor Laura felt no fear,

She tho’t her lover kind and true,

Believed that he’d protect her too.

Confidingly upon his breast

She leaned her head to take some rest.

But soon poor Laura felt a smart,

A deadly dagger pierced her heart.

No shrieks were heard by neighbors ’round.

Who were in bed and sleeping sound.

None heard those shrieks so loud and shrill

Save those who did poor Laura kill.

This murder done, they her conceal

And vowed they’d never it reveal.

To dig the grave they now proceed.

But in the dark they made no speed.

The dawn appeared, the grave not done.

Back to their hiding place they run.

And they with silence wait the night.

To put poor Laura out of sight.

The grave was short and narrow too,

But in it they poor Laura threw.

They covered her with leaves and clay,

Then hastened home ere break of day.

Since Laura left at break of day,

Two nights and days have passed away.

The parents now in sorrow wild

Set out to search for their lost child.

In copse and glens, in woods and plains

They search for her but search in vain;

With aching heart and plaintive mourns

They call for her in mournful tones.

With sad forebodings of her fate

To friends her absence they relate.

With many friends all anxious too

Again their search they do renew.

They search for her in swamps and bogs,

In creeks and caves and hollow logs,

In copse and glens and brambles too,

But still no trace of her they view.

At length upon a ridge they found

Some blood all mingled with the ground.

The sight to all seems very clear

That Laura had been murdered there.

Long for her grave they search in vain.

At length they meet to search again.

Where stately pines and ivys wave

‘Twas there they found poor Laura’s grave.

This grave was found, as we have seen,

‘Mid stately pines and ivys green.

The coroner and jury too

Assembled, this sad sight to view.

They took away the leaves and clay

Which on her lifeless body lay,

Then from the grave the body take

And close examination make.

Then soon their bloody wounds they spied,

‘Twas where a dagger pierced her side.

The inquest held, this lifeless maid

Was there into her coffin laid.

The jury made the verdict plain :

‘Twas that poor Laura had been slain;

Some ruthless friend had struck the blow

That laid poor Laura Foster low.

Then in the church yard her they lay,

No more to rise ’til Judgement day;

Then robed in white we trust she’ll rise

To meet her Savior in the skies.

—Thomas Land