“Streets of Laredo” (Unfortunate Rake, Part Three)

This is the third in a short series of posts on “The Unfortunate Rake.” Read the previous posts here and here.

“So brave, young, and handsome”

“When I got back to Wichita, I met one Zach Potter, a man with whom I had had some difficulty. He was on his way from the range to where he had friends in eastern Kansas. I always tried to make it a rule not to hold enmity toward any man. It was near an ice cream saloon that I met Potter. I addressed him in a friendly manner, and invited him to have some ice cream with me. ‘All right,’ he said, and while seated at the table we discussed our past trouble, its cause, etc., and ended up shaking hands and parting as friends. I have always been glad that we did so, for not long after I heard of his tragic death. Shot to death over a game of cards.”

–from Cowboy’s Lament: A Life on the Open Range by F. H. Maynard

“Streets of Laredo” is such a classic of American music, and specifically music of the Old West, that it’s a challenge to know where to begin and what “trail” to take to tell at least part of its story. Carl Sandburg referred to it as a “cowboy classic” as early as 1927. It was probably barely 50 years old then. Thirty years later, it was for a young Greil Marcus the first folk song that “carried the sting of death,” as he listened to a contestant sing it on a TV quiz show. A recent Western Writers of America survey placed it as #4 on a list of the Top 100 Western songs.

“Laredo” is so familiar that I’ve been curious to understand what it might still have to say, or if it is just an old chestnut. Understanding more about where it started will help us figure that out. What difference do America and “the West” make to the song’s core themes? How does the passing of time figure in changing how the song functions? What does the song in turn say about the West, and how does its story prove influential in the development of later songs and literature about the West?

Almeda Riddle provides a good introduction to get acquainted with the song. She calls her version “Tom Sherman’s Barroom.” I’ll explain why below.

“Rake’s” Western Progress

The American West was fertile ground for murder ballads, many of which have been lost to history. “Streets of Laredo” has staying power. Its story of a cowboy led astray is a common trope. You can hear its echoes in Marty Robbins’s classic “El Paso,” or in “Sonora’s Death Row.” Our dying cowboy is not an outlaw, but he’s “done wrong.” “Streets of Laredo” incorporates a call for compassion for our fallen comrade with a pathos akin to “Pills of White Mercury” (“Unfortunate Rake” pt. 1), but without the overt macho swagger of “Gambler’s Blues” (pt. 2). It keeps the “framing mechanism” usually found in the other two, where the narrator is not the protagonist. Like the other two, this song involves bearing witness to a person’s death, and the dying person’s final desire for dignity, despite their failings.

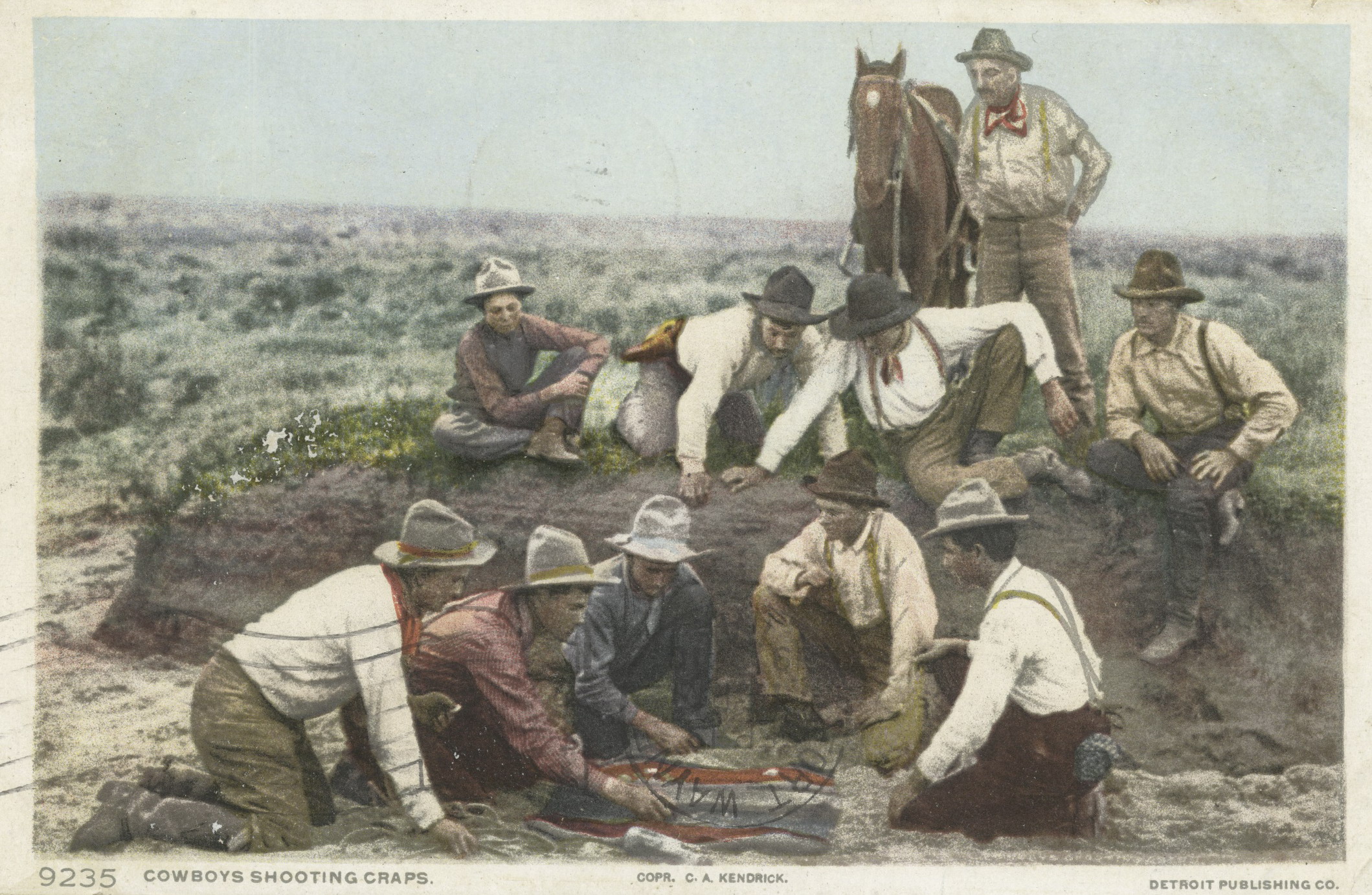

“Pills of White Mercury” makes the cause of its “hero’s” impending death clear. “Flash girls” and venereal disease, formerly treated by mercury pills, have done him in. “Gambler’s Blues” is more oblique about the causes of death and impending death. Although Carl Sandburg termed “Gambler’s Blues” a “gutter song,” it leaves unseemly matters unstated, and provides a mixture of mystery, romance, and death. “Streets of Laredo,” removes both the taint and the hint of disease, leaving a more straightforward murder ballad. The dying protagonist has done some wild living, but he dies from a bullet to the chest. Folklorist Kenneth S. Goldstein euphemistically termed it “lead poisoning.”

In his liner notes to the Smithsonian Folkways album he curated, Goldstein noted the “later cowboy adaptations” of the “Rake” were the most numerous of the three strains of the song we’ve heard. Goldstein captured a couple versions of the cowboy song for his collection. We’ll hear it under a variety of aliases, from “The Dying Cowboy” to “Tom Sherman’s Barroom” to “As I Roved Out” to simply “Laredo.” This Western incarnation of the “Rake” is only about 140 years old, but the “folk process” has worked it over pretty well, and continues to do so. “Laredo” merges the themes of compassion and dignity found the earlier “Rakes” with the wide open imaginative landscape of the American West. The West provided space for art and literature to explore moral and social themes before outer space became the (final) frontier.

Bruce Buckley performs one version on Goldstein’s collection, also set in Tom Sherman’s Barroom.

Harry Jackson’s version takes it to Laredo, Texas, which is more familiar to most listeners today.

Lyrics for these versions appear in Goldstein’s liner notes.

“Streets of Laredo” is a distinctly American creation, but one that bloomed forth on the plains because of the popularity of some Irish forebears. The first forebear, with regard to theme, was “The Dying [or Bad] Girl’s Lament,” which was popular among cowboys. We know it’s a descendant because the funeral instructions usually make little sense in the Western context. They are a holdover from the military funerals of earlier “Rakes.” The second Irish forebear was “The Bard of Armagh,” which provided the tune for many versions of the song. Here is Tommy Makem’s performance of “The Bard of Armagh”