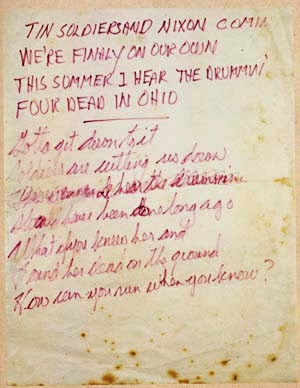

Should’ve Been Done Long Ago: “Ohio” Part 4

|

| Neil Young, New York 1970 photo by Joel Bernstein |

This is the fourth and final post of our initial discussion of Neil Young’s “Ohio.” Here are the first, second, and third posts.

I know, I know. On the fourth post on Neil Young’s “Ohio,” you’re thinking that I should have been done long ago. A few loose ends didn’t fit neatly into the previous posts, and I want to tie them up by exploring further what makes Young’s song so effective and what made it such a big hit.

Was it effective and popular because it was first? Was it because Crosby, Stills, Nash, & Young were a super-group at the top of their game, with close connections to the counterculture? Was it the evocative and challenging lyrics? Was it the angry guitar riffs? Was it the martial beat? All of these factors played a role.

Young’s song is extraordinarily simple, just a stanza and a chorus, each repeated once, with the lyrics pointed enough, yet open-ended enough to direct the listener’s outrage, and also allow for multiple ways of finding meaning within the words and music. You may remember from the last post that Professor Jerry M. Lewis said that he found that students seemed to respond to the music and the beat more than the lyrics. The song would be played over and over again from speakers in dorm room windows on the night of the vigil.

Lewis also mentioned that he was puzzled by the phrase “should have been done long ago.” The phrase could be read as “soldiers cutting us down should have been done long ago,” although that seems quite counter to Young’s sentiment. I can offer at least two potential interpretations of Young’s in response:

1. “We should have been done long ago” with this kind of violence.

2. We long ago should have come to the realization that we are “on our own:” — that the state will protect itself before it protects its citizens. That’s the realization that we gotta get down to.

I’m not sure that either is right or satisfactory, and they are not compatible with one another, but it’s far from the first or only time that an artist has resisted definitive interpretation. The key here is that Young not only protested, he made art–and in that art we are able to move around and find the meaning for ourselves. And, as George MacDonald has said, the better the art, the more it means–the more meanings it can have.

|

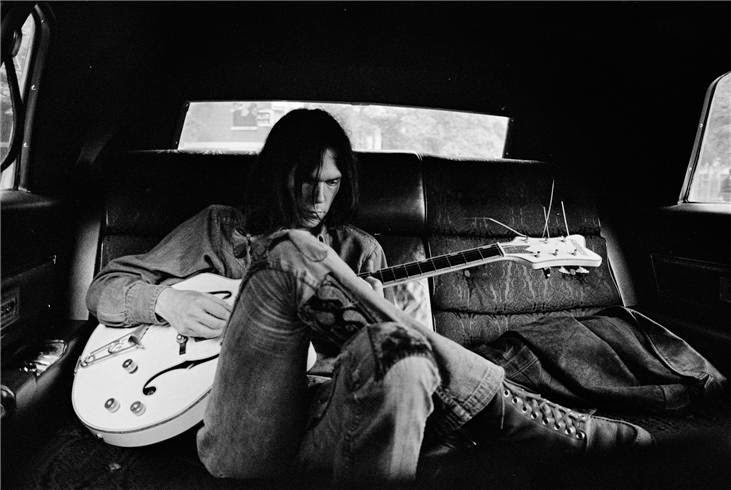

| Bruce Springsteen, with Steel Mill |

Some of our answer will be found in the song itself. Perhaps a few more can be found by contrasting Young’s approach with that taken by other artists.

Young and his friends got the jump on all other musical interpreters. I’m going to review some of those other songs here today, in this last post on “Ohio.” You may find one that feels more compelling or better suited to the gravity of the events it addresses. You’ll not find one more popular than “Ohio.”

Will we run through the fields again

Oh will the barbed wires cut our legs again

Don’t you ask me now ’cause I don’t know how we can

And hurry, we’ll be late for the show

Where was Jesus in Ohio?

Springsteen played the song solo within the band’s set. The Springsteen Lyrics web site contains the full lyrics and the story behind the song’s performance and recording. The recording quality on the clip is poor, but the song is my favorite among these “also rans.” Springsteen draws the parellel of citizenship between soldiers and protesters, patriots both, that gets echoed in other songs. This one also has the feel of a Phil Ochs, “all the news it’s fit to sing” style song, coming in equal parts from the newspaper and Springsteen’s heart.

|

| Steve Miller Band |

Killin’ Four Blues

The May 4 events at Kent State also inspired a few artists not known for protest music of any stripe. The Steve Miller Band recorded “Jackson Kent Blues” in November of 1970. Miller’s protest is an amped up semi-talking blues–sung, but involving story-telling, and a rapid fire name-checking responsible parties and other events along the way. He also links in the Jackson State shootings that followed Kent State by a few days. The end gets rather spacy and psychedelic, adding the invitation to “give peace a chance.”

Space Cowboy’s back to tell you the score

Nothing any good has ever come of a war

Got those low down, profound, killin’ four blues

The Beach Boys recorded “Student Demonstration Time” in 1971. They also turn to the blues, with inflections of the Beatles, and a healthy dose of Leiber and Stoller’s “Riot in Cell Block Number 9.”

America was stunned on May 4, 1970

When rally turned to riot up at Kent State University

They said the students scared the Guard

Though the troops were battle dressed

Four martyrs earned a new degree

The Bachelor of Bullets

I know we’re all fed up with useless wars and racial strife

But next time there’s a riot, well, you best stay out of sight

To my ear, their take is more callous. It’s not as raw and emotional as Young or Springsteen, or even as sympathetic as Miller. Perhaps it was well suited to its musical moment in 1971. It sounds thematically off-key now.

The progressive rock band, Genesis, takes a look at these events from a different angle, writing an evocative and ironic account of the thoughts of the Guardsmen on May 4. The song contains no direct reference to May 4 or Kent State, but gives the listener a good deal to think about in putting these words in the Guardsmen’s minds and mouths.

Soon we’ll have power, every soldier will rest

And we’ll spread out our kindness

To all who our love now deserve.

Some of you are going to die –

Martyrs of course to the freedom that I shall provide.

Jazz artist, Dave Brubeck, produced an entire cantata, entitled Truth is Fallen, in May of 1971, and released on album in 1972. It responds to the 1970 killings at Kent State and Jackson State. You can read the lyrics on this image file, and you can read Brubeck’s liner notes here. The piece was commissioned for the opening of the Midland Center for the Arts in Midland Michigan. Brubeck dedicated the piece “to the slain students of Kent University and Mississippi State [sic], and all other innocent victims, caught in the cross-fire between repression and rebellion.”

|

| Dave Brubeck (1920-2012, photograph by Redferns) |

The piece as a whole is a wild ride, incorporating strains of backwoods folk music, New Orleans-style jazz, and martial or patriotic songs like “Taps,” “Over There,” and “The Star Spangled Banner.” Brubeck’s liner notes, linked above, go into much more thematic detail. We are giving short-shrift to the full scope of Brubeck’s cantata/requiem here, and may need to come back to it another time, however much it falls out of our normal milieu of folk and popular music.

It Could Have Been Me

In the singer-songwriter/folk music genre , Barbara Dane gives a detailed musical accounts of the events of May 4. Her “Kent State Massacre” is reminiscent of early Bob Dylan troubadour-style protest music–with the story very closely followed by “the lesson.” In keeping with the title on which the album appears, Dane turns to a fairly explicit political exhortation at the end of the song.

Alli Krause and Sandy Scheuer

Marched and sang a peaceful song.

Like Bill Schroeder and Jeff Miller,

They did not think it wrong.

They laughed and joked with troopers,

And some to them did say:

We march to bring the GIs home,

And we are not afraid.

Similarly, singer-songwriter Holly Near takes a more polemical take, expressing solidarity with the dead students in “It Could Have Been Me,” and contextualizing the demonstrations at Kent State among other global justice struggles. Near has a clear niche in social justice oriented songwriting, and this song is one of her flagship pieces in that particular musical voyage.

Near explains in this YouTube clip, which includes a performance of the song, that she’d been invited in the early 70s to participate in an on-campus memorial at Kent State.

Students in Ohio 200 yards away

Shot down by a nameless fire one early day in May

Some people cried out angry you should have shot more of them down*

But you can’t bury youth my friend

Youth grows the whole world round

[* If you doubt this, watch here.]

Heroes Every One of Them, Theirs and Ours Alike

Heroes Every One of Them, Theirs and Ours Alike

As a final piece to add to an incomplete list of musical responses to the May 4, 1970 shootings at Kent State, I want to add “Nue Ba Den,” by Mike Morningstar. We’ve listened to this one before, in our posts on Stan Rogers’s “Harris and the Mare.” Although only tangentially about Kent State, Morningstar’s piece is similar to Springsteen, and in a way to Genesis and Brubeck, in drawing parallels between the protesters and soldiers–different ways to serve as citizens, to be sure, but clearly not apathetic to the well-being and right-doing of their country. The songwriters find people on all sides serving as pawns in a much larger game of power played by others. Morningstar, himself a veteran, gives a richly tangible view of the sacrifices entailed by citizenship in a time of conflict–“as their knowledge pierced our being just as surely as hot lead.” This song is one of my favorites, and that’s in no small measure attributable to the solidarity of the human spirit embedded within it.

Thanks very much for reading these posts on “Ohio.” They’ve taken me a while to put together. Even at over 40 years removed, it proves quite difficult to separate the music from the strong feelings around the events themselves, and I’m close to people who still feel some of those days very deeply. For a song with only two verses, I’ve felt like there’s been a lot to say. I knew that one post wouldn’t do it, but didn’t want the loose ends hanging out there for too long.

We’re about to go on our annual holiday hiatus. I hope to get a “gone fishin'” post out to you early next week. We’ve got some exciting news to share, I hope, so please stay tuned.