Revolution Blues: How Charles Manson Murdered the ’60s (Part Two)

This month marks the 46th anniversary of the Tate/LaBianca murders committed by Charles Manson and his cult-like Family. A nightmarish event with lasting cultural impact, music is central to its story. This and last week’s posts explore the connection.

At the edge of town…

My fellow Americans, our long national nightmare is over.

— President Gerald Ford (1974)

In the mid-’70s, Neil Young was in no mood to be anyone’s flower child. So the complex, at times irascible musician made a trio of edgy, introspective albums designed to please no one but himself. Time Fades Away (1973), On the Beach (1974), and Tonight’s the Night (1975) were records of tough, ambivalent rock unleashed on a public expecting earnest folk-pop (like 1972’s “Heart of Gold”) or at least obvious message songs (like 1970’s “Southern Man”). Instead, listeners got dark ruminations on a cluster of themes – drugs, dissolution, the downside of fame – nagging Young as the new decade hit high gear. Of the three, On the Beach was the least musically raw and outright despairing. But its caustic lyrics remained bitter, at times savagely so. A key track on Beach – inspired by Manson – was called “Revolution Blues.”

Well, we live in a trailer at the edge of town

You never see us ‘cause we don’t come around

We got twenty-five rifles just to keep the population down

But we need you now and that’s why

I’m hanging around

Neil Young: “Revolution Blues” (1974)

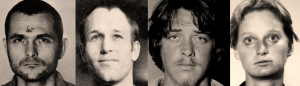

By 1974, the heyday of the Manson Family had passed. The Tate/LaBianca killers were behind bars, their death sentences commuted to life imprisonment when California abolished capital punishment in 1972. A ten-month trial had kept Americans entranced, as the gruesome and bizarre details of the crimes were made public, and Manson made headlines by disrupting the proceedings and issuing threats while a circle of his followers kept vigil on the street outside the courthouse. Manson carved an “X” into his forehead (“I have ‘x-ed’ myself from your world,” the evil messiah explained; later he modified it into a swastika) and Family members – after insisting for months that they acted independently from their guru – all followed suit. For verdict day, they shaved their heads.

Mysterious deaths occurred, during and after the trial. A Manson follower was found dead with a bullet in his head at a Family crash pad – from playing Russian roulette, those present told police (who had no idea they were talking to Family members). But the gun had been fully loaded and wiped clean of prints. A Family associate was found dead in a London hotel, his wrists and throat slit. It was ruled a suicide, though once more police were unaware of his Family connection. Mid-trial, one of Manson’s own defense attorneys (all of them forced on the accused mass murderer, who wanted to defend himself) disappeared. Months later, his decomposed corpse was found trapped under a boulder at Sespe Hot Springs. Some of these deaths may have been accidental or self-inflicted. But at the time, each tweaked the paranoia of a nation still adjusting to the homicidal hippie paradigm. Meanwhile, police studied possible links between the Family and various unsolved murders.

Mysterious deaths occurred, during and after the trial. A Manson follower was found dead with a bullet in his head at a Family crash pad – from playing Russian roulette, those present told police (who had no idea they were talking to Family members). But the gun had been fully loaded and wiped clean of prints. A Family associate was found dead in a London hotel, his wrists and throat slit. It was ruled a suicide, though once more police were unaware of his Family connection. Mid-trial, one of Manson’s own defense attorneys (all of them forced on the accused mass murderer, who wanted to defend himself) disappeared. Months later, his decomposed corpse was found trapped under a boulder at Sespe Hot Springs. Some of these deaths may have been accidental or self-inflicted. But at the time, each tweaked the paranoia of a nation still adjusting to the homicidal hippie paradigm. Meanwhile, police studied possible links between the Family and various unsolved murders.