There’s a train a-coming: “People Get Ready” – CwD10

people’s spirits. Anytime you can get something that lifts your spirits and also speaks to the

reality of your life, even the reality of oppression, and at the same time is talking about

how you can really overcome; that’s terribly important stuff.”

— The Reverend C. T. Vivian

Conversations

As I was watching a PBS roundtable discussion during one of the political conventions this summer, commentator David Brooks noted the significant number of speeches offered at both major party conventions by people who had experienced the death of a loved one. Brooks found it symptomatic of the cultural moment. Both parties, he said, seemed to be mining themes of loss. Given our milieu here, Brooks’s comments drew my attention. What really caught me, though, was that while he was making this observation, the conventioneers were being entertained by a band performing Curtis Mayfield’s 1965 classic, “People Get Ready.” Here’s the clip. (Skip to the 50:20 mark for the relevant segment.)

I found the juxtaposition funny, and slightly complicated. For those unfamiliar with the song, it uses a train as a symbol of coming divine judgment and salvation. That metaphor, however, is itself a metaphor for political freedom. Although it outwardly invokes preparing for a journey to heaven, it emerged in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. “People Get Ready” is thus both a “Conversation with Death” and a Freedom Song. Brooks talks about the theme of loss. Themes of sacrifice, fear, and insecurity emerge from that kind of political discourse. The parties perhaps found that speakers who were grieving loved ones rhetorically compelling. “People Get Ready” turns death on its head, and provides reassurance, inspiration, and hope in this world—despite the evidence.

“People Get Ready” is a “Conversation with Death” that takes place indirectly and in code. The song’s coding makes it a nuanced conversation, but one that generates insight into how music involving “final judgment” need not always be ominous. It can instead be a resource to support people taking up struggles for freedom. Unsurprisingly, it is just as much a “Conversation with Life.” Same conversation. The story about the song’s relationship to its moment, though, has at least a little more to tell us about music and mortality.

“A spiritual state of mind”

Bob Marovich, who runs the Gospel Memories Radio Show and is the Founder and Editor of the Journal of Gospel Music, directed me to two books by Robert Darden on the history of gospel music and its relationship to the Civil Rights Movement. Darden’s book, Nothing but Love in God’s Water provided one clue to the origins of “People Get Ready” that gave me further reason to take it up here.

Darden writes, “Mayfield said that the gospel-influenced title track was written in response to the March on Washington and the deadly church bombing in Birmingham.” As with “What’s Going On,” which was written in response to police attacking protesters in California, this kind of origin story further placed “People Get Ready” in our milieu as a musical response to violence—although clearly not a story of it.

Darden writes, “Mayfield said that the gospel-influenced title track was written in response to the March on Washington and the deadly church bombing in Birmingham.” As with “What’s Going On,” which was written in response to police attacking protesters in California, this kind of origin story further placed “People Get Ready” in our milieu as a musical response to violence—although clearly not a story of it.

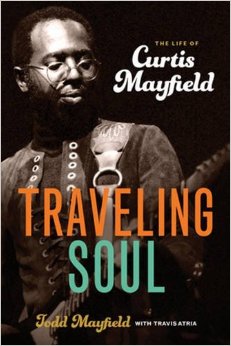

Todd Mayfield’s recent biography of his father, Traveling Soul: The Life of Curtis Mayfield discusses the song’s origins in more general terms. He doesn’t mention Birmingham specifically, but violence surrounding the broader movement does play a role. He opens the chapter with a brief narration of the February 21, 1965 assassination of Malcolm X. Although Curtis Mayfield wrote the song before this date, his son’s account suggests that both that assassination and this song grew out of the same fragmentation. He writes:

“The months leading to Malcolm X’s assassination marked the most intense and fractious period since the movement had begun. As his biographer Manning Marable wrote, ‘The fragile unity that had made possible the great efforts in Montgomery and Birmingham was showing signs of strain. The arguments between so-called radicals like John Lewis and more mainstream black leaders like King and Ralph Abernathy had not abated, and as long-desired goals finally came within sight, they had the peculiar effect of further splintering the movement.’

“Watching the movement unravel around him, Dad found solace, as always, in his guitar. In what he called ‘a deep mood, a spiritual state of mind,’ he put together the follow-up to ‘Keep On Pushing.’ He showed the song—a breathtaking ballad called ‘People Get Ready’—to [arranger] Johnny [Pate].”

Todd Mayfield mentions that his father was at this time also mourning the loss of “his hero,” Sam Cooke. Cooke’s death was not directly related to the Civil Rights Movement. Mayfield’s biography doesn’t specifically mention the bombing in Birmingham, but clearly connects the song to the disruptions the movement faced in that period.

Image from the Audobon Ballroom following the February 21, 1965 assassination of Malcolm X (source: Wikimedia commons)