No Mercy at All – “The Cyclone of Rye Cove”

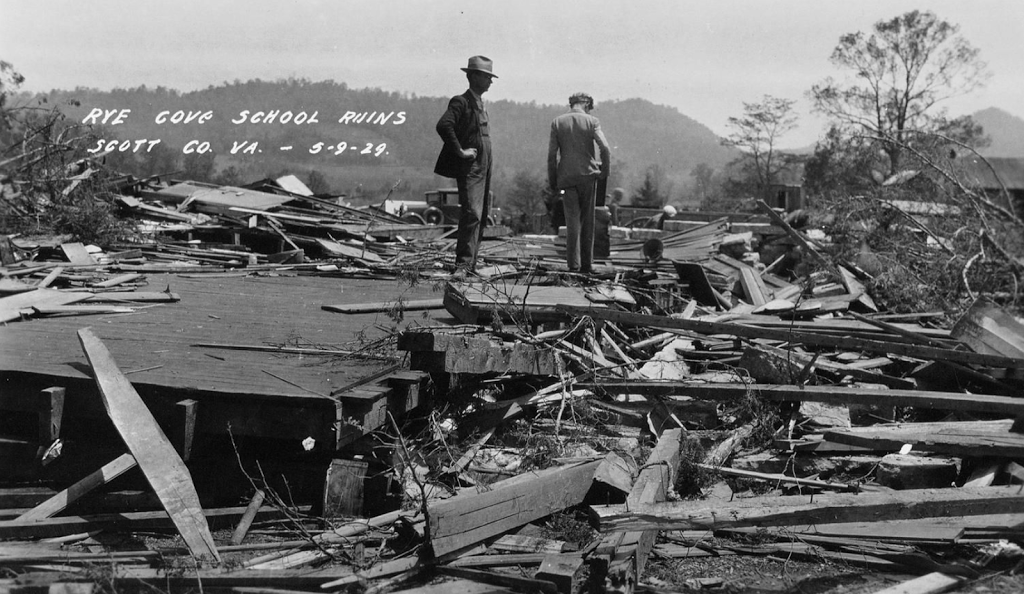

“Rye Cove School Ruins, Scott County, Virginia, 5/9/29” – Photographer unknown – Library of Virginia

Introduction

Nature has no mercy at all. Nature says, “I’m going to snow. If you have on a bikini and no snowshoes, that’s tough. I am going to snow anyway.” – Maya Angelou, from Conversations with Maya Angelou

It’s time to push the boundaries of our definition of ‘murder ballad’ once again.

We’ve seen “killers plain and fancy” here at Murder Ballad Monday, but never have we accused the greatest killer of all. Perhaps we are loathe to indict Nature. Brutal though they might be, Earth and Sky are our Great Parents – the source of all blood, bone, and breath.

Of course, the reason we demur may be as philosophical as it is elemental. There is no court to which Nature answers. As Maya Angelou reminds us, what we think or feel about Nature’s power is irrelevant. It will do what it will do, and the best we can hope or pray for is to be out of the way when Nature brings great violence in to our lives. We can’t think or feel our way out of confronting that fundamental truth. And when the damage is done, if we are left alive, the best we can do is spill tears that will join once again with rivers and oceans.

Well, maybe we can do a bit more. We do have art, after all. We can evoke what it means to be briefly alive in a world of merciless beauty. We can write, paint, dance, and sing – after we cry.

Today’s short post will focus on a ballad wherein Nature does the killing. I’ve often found it to function in a manner quite similar to murder ballads; so I knew, eventually, I’d be writing this piece for our strange little blog. I chose to limit myself to one song about Nature’s lethality to start. I know a few more that affect me in much the same way, and I will likely write about them when the time comes. However, I am sure there must be even more out there, and I would love to hear from any of you about similar ballads. There’s nothing saying we can’t turn this particular post into a series!

Dying on a pillow of stone… “The Cyclone of Rye Cove”

After I moved out on my own and was able to save up a little spending money, I purchased a used copy of Rural Delivery No. 1 by the New Lost City Ramblers. It was an LP, so I couldn’t play it on that long drive back from Boston to the Berkshires. But the next day, I fired up my turntable and I heard this – and I couldn’t believe it.

Oh listen today in a story I tell

in sadness and tear dimmed eyes

of a dreadful cyclone that came this way

and blew our schoolhouse awayRye Cove, Rye Cove

The place of my childhood and home

where in life’s early morn I once loved to roam

but now it’s so silent and loneWhen the cyclone appeared it darkened the air

and the lightning flashed over the sky

and the children all cried “don’t take us away

and spare us to go back home”There were mothers so dear and fathers the same

that came to this horrible scene

Searching and crying, each found their own child

dying on a pillow of stoneOh give us a home far beyond the blue skies

where storms and cyclones are unknown

And there by life’s strand we’ll clasp with glad hands

our children in a heavenly home

My introduction to the song was back in the early ’90s, when I was a folk-music neophyte and before the explosion of the Internet. I knew I’d never heard anything quite like it, but I was satisfied to engage it simply through its overwhelming emotion. Eventually though, because I could never quite forget it, I was compelled to discover its history.

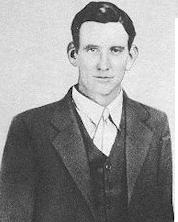

The Carter Family first recorded this song, one of their originals, for Victor in Atlanta on Friday, November 22, 1929. – Their recording session started a week before Thanksgiving, only six months after the tornado struck.

Alternate recording, on radio, ca. 1938

This song is entirely authentic, but you probably already figured that if you listened to it. And, unusually for the ballads we consider, we can know much of what there is to know about its inspiration. It is horrible, but uncomplicated.

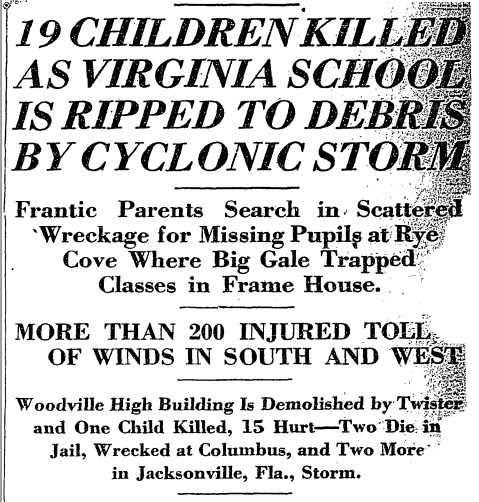

A.P. Carter wrote this song as a direct response to his experiences in the aftermath of a cyclone that destroyed the two-story, seven room schoolhouse in the community of Rye Cove on May 2, 1929. Carter was a native of Scott County, and was close enough to render aid in Rye Cove immediately after the tornado came through. What he saw was unimaginably painful. This linked Encylopedia Virginia article tells the history in detail. Here are some fascinating newspaper clippings, as well, that help one imagine the scene.

As they would in most traditional murder ballads, the lyrics do more than tell the horrible news. There is a familiar depth of reflection. However, unlike most traditional murder ballads, there is no overt moral drawn for the listener. Yes, the final verse looks to an afterlife in Heaven; but there is no evil-doing in the song and none of that ‘old time religion‘ exhorting sinners to repent before God takes them as He will. There is only terrible sadness at the violent death of the innocent, and the understandable hope that parents might see the sweet faces and touch the small hands of their children once again.

Does it work like a murder ballad?

Is a disaster song like a murder ballad? I guess you get to decide that for yourself. Murder ballad or not, for me, this song works. It is an effective psychological tool for navigating the invisibly thin line between life and death. The articulation of such suffering allows me safely to feel what otherwise might overwhelm me and reduce me to despair, to find expression for the rawest of emotions when they might otherwise hollow me out completely. For example, “Rye Cove” helped me both after the Newtown Massacre and the destruction of the Plaza Towers Elementary School by a tornado in Moore, Oklahoma.

Eight decades do not keep A.P. Carter’s words from hitting their mark, nor do they lessen their impact. They are sung from darkness into light and strike a listener by surprise, like the twister they evoke; we are wholly unprepared for such intensity.

One sees images that sever heartstrings, and precisely the same ones captured in Moore, by journalists. The pictures are almost too much to bear. But a song is capable of giving us more than today’s media. It can help fill the empty spaces such pain carves into us, as it clearly did for A.P. Carter.

What a wonderful thing for A.P. to give to himself, and to his community, after seeing all that. What a gift he gave in refraining from drawing a moral, in allowing us to do it for ourselves. Had he done otherwise, his words might seem an imposition to those most directly affected by the loss. Such art must always risk being an imposition, I suppose; but at least Carter wrote it from his heart and not his head, and so gave everyone the chance to relate in the same way.

We are indeed lucky that, by 1929, electric recordings were making it possible for local ballads and outstanding rural musicians to find their place in a wider world.

Coda

‘What more is there to say?’ That’s how I feel when I’m done listening to this song. I can discuss endlessly themes arising from the murder ballads that fascinate me, but this song leaves me mute.

Luckily, there is one more performance of this ballad that any lover of traditional country music would recognize as a worthy, heartfelt rendition. We’ll close then with Doc Watson’s “Rye Cove.”

Doc’s medicine always does the trick, I’m sure you’ll agree. It doesn’t wholly eliminate the bitterness of the truths we all must swallow, but it makes their understanding just a taste sweeter.

Good day, friends – and thanks for reading!