“Frog Prince” by Arthur Rackham

My chosen song this week has as its origins an English fairy tale about a girl who loses a nice toy and is punished for it. It is a tale that grew in at least two major branches. Along one branch, it became one of our most beloved fairy tales about true promises and true love; in contemporary times, it appears in the fairy tale collections of innocent little girls everywhere, like this one:

Along the other branch, the tale became a mean, complicated murder ballad about betrayal, sexual bribery, and death in extreme circumstances; in contemporary times, this one has appeared most famously perhaps on stage with Jimmy Page and Robert Plant (becoming, in their hands, meaner and more distorted than ever).

“Led Zeppelin acoustic 1973” by Heinrich Klaffs

It’s not hard to guess which branch of the tale I’ll focus on this week, and later in this post I’ll have Led Zeppelin help make introductions to the song. But before I do that, let’s start at the very beginning:

Once upon a time, there was a beautiful young maiden who had a golden ball. The ball was her favorite thing with which to play, but she was careless. One day, she tossed it so high that it fell far beyond her reach, rolling along until it plopped into the dark depths and she could not find it.

Many will recognize this as the introduction to the well-known fairy tale “The Frog Prince,” and will know exactly what happens next. Inconsolable over the loss of her golden ball, the maid promises anything – anything! – for its safe return. And along comes an ugly frog who retrieves the ball and asks for a kiss in return. Although repulsed, the maid ultimately keeps her promise and kisses the frog, whereupon he is transformed into a handsome prince and everyone lives happily ever after. The moral is usually something about the importance of taking care of your things, keeping one’s promises, not judging people based on appearances, and other good things like that.

“The Frog Prince,” Muppet version — what’s not to love?

Not quite as many would recognize this story about a maiden who loses her golden ball as the introduction to another, darker fairy tale. In this tale, in order to get her ball and her prince, the maiden must go through a hell far worse than kissing a frog. Let’s take a look at the full version of the introduction to this fairy tale, entitled “The Golden Ball”:

Once upon a time there lived two lasses, who were sisters, and as they came from the fair they saw a right handsome young man standing at a house door before them. They had never seen such a handsome young man before. He had gold on his cap, gold on his finger, gold on his neck, gold at his waist! And he had a golden ball in each hand. He gave a ball to each lass, saying she was to keep it; but if she lost it, she was to be hanged. Now the youngest of the lasses lost her ball, and this is how. She was by a park paling, and she was tossing her ball, and it went up, and up, and up, till it went fair over the paling; and when she climbed to look for it, the ball ran along the green grass, and it ran right forward to the door of a house that stood there, and the ball went into the house and she saw it no more.

So she was taken away to be hanged by the neck till she was dead, because she had lost her ball.

Ouch! As if this extreme punishment for losing a toy were not enough, the maid must then stand on the scaffold with the noose around her neck as her family members – mother, father, and brother – all come in succession to see her. Thinking that they have come with her golden ball in hand to secure her freedom, the maid tries to negotiate with her executioner for time and for her life. Instead, she is repeatedly devastated to learn that, rather than rescuing her, each of her relatives has come to see her hang:

Now the lass had been taken to York to be hanged; she was brought out on the scaffold, and the hangman said, “Now, lass, thou must hang by the neck till thou be’st dead.” But she cried out:

“Stop, stop, I think I see my mother coming!

O mother, hast thou brought my golden ball

And come to set me free?”

And the mother answered:

“I’ve neither brought thy golden ball

Nor come to set thee free,

But I have come to see thee hung

Upon this gallows-tree.”

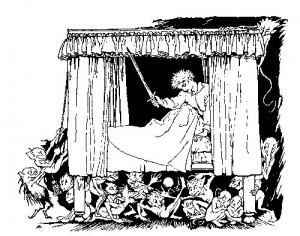

This scene repeats painfully with each loved one, as the noose grows tighter and the executioner grows more impatient. Finally, however, the maiden’s sweetheart appears with the golden ball – to get it he has had to face down a series of very mean giants as well as swarms of “bogles” (a kind of folkloric ghost or bogeyman that kind of resembles a troll — or a malevolent, deformed frog). Nevertheless, he finally frees the maid and they too live happily ever after.

The maiden’s sweetheart fighting off hordes of bogles cavorting with the golden ball.

The evil twin of “The Frog Prince,” “The Golden Ball” evolved into a folk ballad, indexed as Child Ballad number ninety-five and most often known by the name “A Maid Freed from the Gallows.” In its own way just as popular as “The Frog Prince,” the ballad is one of the most long-lived and most varied of the traditional ballads; versions going by more than twenty different names have been identified. Among the many contemporary versions of the song the same diversity in name and style also holds.The contextual details that defined the original fairy tale started to fade even in the early traditional versions of the song, however. Here, for example, is a modern recording of a traditional ballad (one of the versions that Child collected), in which the maid’s sweetheart has completely disappeared — it’s her grandmother who saves her — and no contextual background to explain the import of the golden ball is given:

“Golden Ball,” Rubus (from the album Nine Witch Knots)

As we’ll see, as the song evolves, many defining details from the original tale disappear or change — the nature of the maid’s crime, the motivations of the relatives and loved ones who visit her at the gallows, the kind of objects or bribes they offer for her freedom, even the maid’s gender is up for grabs (particularly in later American versions of the song, for example, she is often replaced by a man).

Most importantly, the maid’s fate is up for grabs as well — it remains ambiguous, or, as in most contemporary versions of the ballad, it becomes clear that she is hanged. In these versions, the driving plot element is not the maid’s final rescue and happy ending with her sweetheart, but precisely the reverse: the hangman accepts all offers for her freedom but in the end he goes ahead and executes her anyway. Which makes this a song not about punishment, but about murder.

Such is the case in Led Zeppelin’s “Gallows Pole” (recorded for Led Zeppelin III, 1970), which remains the most well known version of the song today. As the title suggests, in this version there is no maid and there is no freedom: the person on the gallows is a man and, although his relatives give everything they have to save him (including themselves), he hangs anyway. The only major element that remains from the original tale is the desperate bargaining with the hangman, and just a little bit of gold:

“Gallows Pole,” Led Zeppelin, live recording with lyrics

“Gallows Pole,” Led Zeppelin, higher quality recorded version

With this version, then, we’ve traveled a long, long way from fair maidens, golden balls, cold-hearted relatives, rescuing princes, and happily ever after. In fact, we have the opposite of all that.

So, exactly how and why did the song get from there to here and from that to this? Stay tuned — following a little explanation from Jimmy Page and Robert Plant, we’ll explore the answer in the next post.