Mackie, how much did you charge?

|

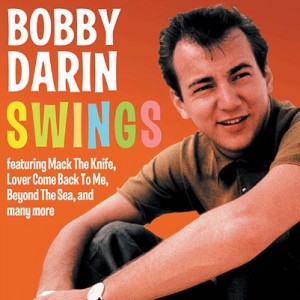

| Bobby Darin |

I fear I’ve become a bit of a crank. My previous post likely creates the impression that I insist that somehow all songs that involve crime or murder must be serious, and that there’s no room for a song that just inherently swings. I actually don’t think this. My point all along in these posts is that choosing to sing a song or listen to it is based on the premise that experiencing that song, whether from within or without, evokes something specific, although often inchoate, in the individual singing or listening. It’s what we keep referring to as how the song “functions.” A central premise of the previous post was to figure out how the song may or may not “function” in a manner analogous to other murder ballads we’ve explored. I think I’ve determined that in many ways, “Mack the Knife” functions differently–at least in those iterations. It remains to be seen, however, if it might be brought back into our fold, so to speak.

I also can’t fault the performers I featured yesterday–well at least Armstrong and Fitzgerald, and some of the singers I’ll feature today–for making the song safer for public consumption. I was explaining to my son the other day how the 60s (as an era, not a decade) represented something of an escape valve from the more constrained post-WWII years, when recovery from the brutality of war and the growing presence of the Cold War made safety and stability something to be cherished. (Not precisely my theory, I suppose. I remember reading an interview with Richard Thompson where he ventured much the same claim.) It’s not too hard to imagine that “Mack the Knife” is running through this cultural force of the “pre-60s.” While other music might be running through the subculture, and the “Great Folk Scare,” as I’ve referred to it, is plying its own course through the culture, “Mack the Knife” may represent the more popular course for the Eisenhour generation. Perhaps it’s a relatively measured dalliance with risk and danger.

We’ve seen a little bit of this before, I think, in Shaleane’s discussion of “Stagger Lee,” in the week showcasing the musical relationship, through murder ballad, between Nick Cave and Johnny Cash. Dick Clark famously made Lloyd Price re-write his already toned-down version of “Stagger Lee” before he would let the song appear on American Bandstand. It was Price’s original, though, that became the #1 hit.

Clark, incidentally, also advised Bobby Darin against performing “Mack the Knife,” apparently not so much because of the content, but because it came from the opera world, and wouldn’t appeal to rock and roll audiences. (We’ll just skip past the fact that Threepenny is not, properly speaking, an opera. Perhaps that only reinforces Clark’s point…) The song went on to become not only a #1 Billboard hit for nine weeks, but was rated by Billboard as the #3 song in the first fifty years of the publication of the Billboard Hot 100. It sold over 2 million copies, and won the Grammy in 1960 for record of the year. (Incidentally, both “Stagger Lee” and “Mack the Knife” get bailed out a bit as murder ballads by one of our go-to-guys for hard-hitting, uncompromising performances, as you’ll see by the end of this post.)

Per the Billboard article linked above, “Mack the Knife” was Darin’s bid to move from teen idol to adult supper club entertainer. He too uses the Blitzstein translation, with Armstrong’s “Lotte Lenya” appearing in the verse. In a way, Darin just injects a little Rat Pack-like affect to the Armstrong arrangement, and he’s off to the races. Here’s a clip of a young Bobby Darin performing the song:

Despite success with a number of other songs, it’s clear that “Mack the Knife” is really the career-maker for Darin. He acknowledges as much in this later recording, which includes some clowning around at the end.

“Mack the Knife” by Bobby Darin (Spotify)

|

| Eartha Kitt with claws bared |

So, what made for Darin’s particular success with the song? At the time he released it, both Armstrong and Bing Crosby had recordings out. Eartha Kitt also released a version in 1959. (Here it is on Spotify. Here on YouTube.) Whether that was before or after Darin’s version, I don’t know, but Darin’s version peaked on the charts in October of that year. My guess is that a handsome, young, white, teen idol making the move to more mature “supper-club” style music was part of the magical combination–and perhaps just good timing. Fans give Darin a lot of credit for “owning” the song, with phrasing, etc., but it’s not clear that he adds a great deal of original artistry to it. But, I’m sure to many he looked like a pretty good kid. So, the song was “safe” with him, perhaps. (That being said, Darin’s performance was banned by the BBC for a time, and some banned it because it was thought to encourage gang violence.) In the end, Darin succeeds in “inhabiting” the song, investing himself in it as a singer in a particularly compelling way, but it’s probably part who he is, and part what he does.

Some are children of the darkness

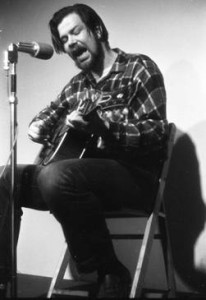

After all this uptempo swing, “Mack the Knife” returns to a bit of musical sobriety in some of the treatments following Darin’s. In a few of these performances, we find some of the elements bowdlerized out of the popular jazz and swing versions–either the crimes or the class critique or both. Dave Van Ronk gets credit, I think, for getting this work of reintroducing a more haunting Mackie back into the streets in 1964.

|

| Dave Van Ronk |

Van Ronk also uses the Blitzstein translation, which we heard Armstrong and Darin, among others, use, but includes a verse they often leave out. Exact translations differ, but Van Ronk gives us:

Some are children of the darkness,

Some are children of the sun.

You can see the sons of daylight,

Sons of dark are seen by none.

“Mack the Knife” by Dave Van Ronk (Spotify)

There’s a sense in which this verse might have a double meaning, with “children of the darkness” referring either to Mackie or his victims. It’s a verse added by Brecht for a film version of the Opera. In Van Ronk’s, both in its tone and through this verse, we get a little closer to the action, so to speak, and we also wind up a little closer to the class critique pursued by Brecht’s original work.

|

| Jimmie Dale Gilmore |

Van Ronk’s version may reasonably be seen as a progenitor of a subsequent treatment by Jimmie Dale Gilmore, who provides another haunting rendition in a track included in the soundtrack of the French film Un prophète. Gilmore brings the arson back to Mackie’s list of crimes.

“Mack the Knife” by Jimmie Dale Gilmore (Spotify) (Lyrics)

The producers of another film, Quiz Show (also about hidden transgressions), also saw fit to include “Mack the Knife” in the credits to that film. The relationship of “Mack the Knife’s” themes to the movie’s, though, is far less interesting to me than Mark Isham’s arrangement, and Lyle Lovett’s vocal performance. [Update 3/28/13: The first recording of this I posted was removed by the Fall of 2012. I just found a new link with this performance.]

This is a truly remarkable performance. Isham’s arrangement is initially very square in any number of ways–plodding rhythm at first, soothing strings, hearkening back to Weill’s original in the main part of the song, but with jazz breaks and a building intensity. The lyrics bring back the broader range of Mackie’s alleged crimes–murders of women, the “violation” of the “child-bride in her nightgown,” as well as the arson. If you ask me, this might be the first version we’ve heard that generates genuine empathy for the victims, perhaps returning us to the tone of the murder ballad so missing in the jazz versions. I’m not sure if it’s Isham’s arrangement or Lovett’s singing that accomplishes this. Just my opinion, but I think it’s a remarkable accomplishment, particularly after so much has been done with the song.

|

| Lyle Lovett |

Lovett’s performance might be my favorite of the bunch, but I can’t conclude this post without giving respectful attention to another artist who brings us a Mackie sufficient to his menacing roots. Just as with Isham’s arrangement, Nick Cave’s puts us in mind of the original, squarer, instrumentation and arrangement of the tune and, through a combination of lyrical bluntness (within the constraints of the song) and a clear performative energy, gives us a Mackie we have reason to fear. This, my friends, is not a “Mack the Knife” for the faint of heart.

“Mack the Knife from the Threepenny Opera” by Nick Cave (Spotify)

Getting Away with It, or Not

So I suppose a question for you, gentle reader, is whether you think the core “murder ballad” resonance in “Mack the Knife” lies in the song, the singer, or the arrangement. Another, perhaps similar, question is why we might choose to “play” with such a character as Mackie Messer and when. What does his kind of fictional threat represent to us in times when we face real life threats from a number of sources?

I think I’ll be able to manage one more post for this week, either tying up some loose ends or creating a few more; diving into some harder-driving rock performances and going on a bit of a world tour with our friend Macheath. I’ll catch you on the flip side.