Lamkin – A most brutal bloody ballad.

A ruined castle in Scotland. By Richard Webb, CC BY-SA 2.0

Introduction

Fragments of time and history filter down to us in the Child ballads. We get whispers and incomplete stories that make us ponder what ‘really’ lies beneath. This is deeply true in the case of “Lamkin.” Like so many of the ballads collected by Francis James Child, the ‘truth’ of it can sometimes be found around the edges. This gruesome ballad is fascinating. Not only is it one of the bloodiest of ballads, much also hides at the edges, offering fragments of insight into how it came to be.

“Lamkin” (Child ballad no. 93) takes the murder ballad to a different level. Its story goes beyond simple revenge or straightforward murder. As the ballad progresses, the level of violence becomes increasingly psychotic and unsettling. There is a deep dark heart at the centre of “Lamkin” and at the end of the ballad we are left bewildered, struggling to make sense of the violence. In some ways, “Lamkin” has a modern feel, and one we can see in random acts of violence such as a school shootings or a serial killer. The central question invited by this ballad is why did Lamkin become so violent? The answer, if such a thing is to be found, is surely multi-layered and complex.

Lyrics below

Whispers around the edges.

I want to set out the background to this ballad by looking at two aspects hovering around its edges. The first is the historical and deeply fascinating figure of Michael Scotus or Scot. King Alexander II made Scot’s father a knight at the start of the 12th century. It is said that Scot grew up with his family in a tower in Balwearie in Fife, the same Balwearie that features in the Lamkin ballad. Scot was a very gifted scholar. He first studied at Oxford, another indication of his aristocratic roots and then he went on to both Paris and in 1217 to Toledo University in Spain.

His attendance at Toledo and his particular skill in developing and practising occult sciences drew him to people’s attention. There is a story of the King of Scots, probably Alexander II, summoning Scot for his assistance, as Alexander was getting fed up with French pirates raiding Scottish ships. Scot goes to visit the French King and, opening up his Book of Might, he summons a demon black horse. Scot orders the demon to bang his hooves three times. The first time all the church bells in Paris start ringing. The second time the roofs on the King’s palace start to loosen and fall. As the demon is about to bang his hooves a third time, the French King agrees to stop the pirates. It was surely this kind of reputation that led to Scot being mentioned in Dante’s Inferno in canto XX.

Canto XX By Stradanus – Own work, 2007-10-25, Public Domain.

The ‘Wizard of Balwearie’, as Scot became known, also used his powers closer to home, and it is this which starts to cast a shadow over our ballad. The road to the tower of Balwearie was said to have been built by demons ordered and controlled by Scot. The Devil himself turns up and wants to help build the road. Annoyed by the easy nature of the work, the Devil asks Scot for a more challenging task. Scot eventually gets so fed up with the Devil’s pestering that he sends ‘Auld Nick’ to the beach in Kirkcaldy and orders him to make a rope out of sand. This becomes a never ending task and the Devil eventually grows weary and dies.

In John Burnett’s excellent book Robert Burns and the Hellish Legion, he explores the role of the Devil in Scottish folk tales. He states:

“The Devil lived in Hell, except when he appeared ‘going to and fro in the earth, and…. walking up and down in it’, as it says in the Book of Job. This precedent made it possible for him to be witnessed in the Scottish countryside. In his appearances, re-told in folk tales, he was often mischievous rather than evil.” (Burnett, p28)

Burnett goes on to highlight how the Devil could be tricked and this directly links to the story of Michael Scot above.

“If the Devil is active and present, then there have to be ways of dealing with him. In stories, people were allowed to use any means to trick him. In one widespread tale he made a wager with a farmer that he could cut more corn than him. The night before, the farmer planted hundreds of harrow tines (iron spikes) in the area the Devil was to mow: they blunted the Devil’s sickle, and sharpening it slowed him down.” (Burnett, p31)

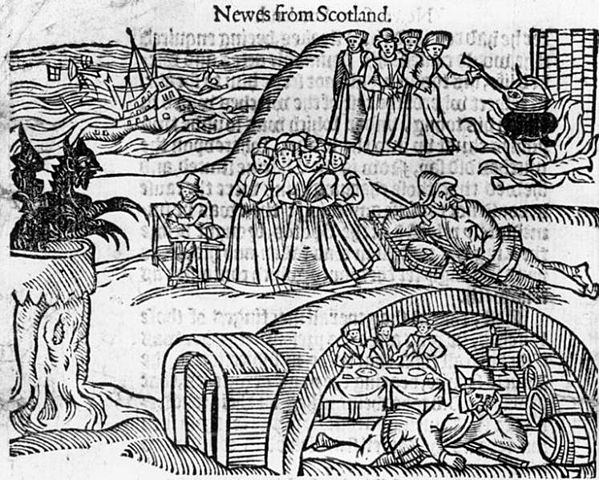

The North Berwick Witches meet the Devil in the local kirkyard, from a contemporary pamphlet, Newes From Scotland By Unknown – googleimages, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13223025