Jon Langford interview, Part Three

|

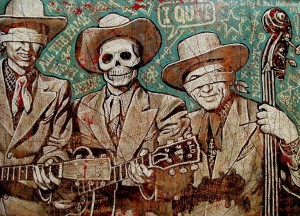

| Lofty Deeds, Jon Langford |

This is the final installment of our interview with Chicago musician and artist Jon Langford. After recording three albums of murder ballads, he seemed like the ideal candidate for a Murder Ballad Monday sit-down. You can also read or re-visit Part 1 and Part 2. Today we find out more about Langford’s punk roots, his attachment to ‘journalistic’ music, and whether or not he’s ever written a murder ballad himself. Again, I’ve included the audio of our interview, with a couple of songs thrown in for your ear bud pleasures.

MBM: I know you sang “Delilah” on the two-disc compilation, the second one. But the first one you sang another song with Sally Timms . . .

JL: “The Plans we Made”

MBM: Talk about that.

JL: That’s a song by Lonesome Bob (aka Robert Chaney). It’s pretty sick (laughs).

MBM: How so?

JL: Oh, don’t they both, they both kill their . . . it’s a couple singing. And they both send their spouses into the wild blue yonder. But then a court and then they walk down the aisle to the gurney, to the lethal injection.

MBM: That’s a real death row song.

JL: it was a modern sort of take on it. And that’s what sort of interested me about alternative country music. That a lot of people went back to those themes, whereas country music has abandoned all that and is singing about some kind of mythical, Republican, rural small town fantasy.

MBM: It becomes the sound of “either you’re with us or you’re against us.”

JL: Yeah, this kind of paranoid rural crap. Then these songs, people like Freakwater, The Handsome Family, and Robbie Fulks, Lonesome Bob Chaney and a bunch of people I knew in Nashville, like Paul Burch, people who were fiddling with stuff from the classic tradition. That was interesting to me about alternative country, and what was interesting to me about doing the Pine Valley Cosmonauts project. We did an album of Johnny Cash covers when he wasn’t very popular. And then we did a Bob Wills thing when . . . I don’t think Bob Wills is popular now, (laughs) I don’t think he ever had a resurgence! But we did that just because I wanted to see how it worked.

MBM: That period in which you made The Executioner’s Last Song you get this emergence of, some people call it insurgent country or alternative country as you’ve called it. What was driving it do you think?

JL: I think that industry control. If you look at country radio George Jones and Merle Haggard and Johnny Cash couldn’t get on it, you know? And it was almost a sort of Stalinist domination, people were written out, cut out of the history. And what was exciting to me about country music when I first heard it was the subject matter and that way of dealing with what seemed like . . . you know a lot of it seemed really urban to me. Merle Haggard had songs about skid row, country boys being in the city, working in factories and dreaming of being home. All that subject matter seemed really real. And why it struck a chord for me is that’s what we were trying to do with The Mekons, with punk rock. Our version of punk rock was very simple songs. Anyone can do it was was our mantra, that you could form your own band and anyone could write a song. Not trying to do big chest beating songs about smashing the system but sort of writing songs that described situations from real life, that as a political act.

MBM: Why is that a political act?

JL: Because it’s counter to mainstream culture, which doesn’t involve that too much, I think. I mean most of the rock music that I listen to in the 70s was about elves and wizards. You know? I thought Led Zeppelin was really cool until . . .

MBM: Until you heard their song about The Hobbit?

JL: (singing) “In Mordor/Gollum’s gonna come and steal my baby” and all this. What the hell are they on about?

JL: A friend from Chicago was the musical director at WZRD . . .

MBM: Oh yeah, the Wizard!

JL: The Wizard came, talking about elves and wizards. And he came over to England and said The Mekons were like a country band, and he gave me all these cassettes. And that’s where I first heard all the drinking killing fighting cheating songs. And he said “That’s what you’re like. It’s just three chords and most of the songs are about drinking in a bar and failed sexual relationships. And I thought that’s what most of our songs are about.

One of our things is that the barrier between the artist and the audience, we wanted to get rid of that. We used to get people up on stage to just play like “Stairway to Heaven” or something. And it was always a disaster, it never worked (laughs). We wanted to break down that wall. And then people like Merle Haggard, I went to see him play, and the songs he sang and the way he looked at his audience, I thought he’s talking directly to them, about their lives, in a very effortless and profound sort of way.

MBM: Do you in all the study of murder ballads, by making those 3 compilations . . . well, first. I feel like you didn’t really answer when I asked you the question before, about why murder ballads, to talk about the injustice of murder, at least murder by the state . . .

JL: It was a conceit.

MBM: Like a provocation in a way?

JL: Yeah. I just thought it was kind of cheeky. But I liked those songs. So I went into it with the idea of maybe I’ll find out what I like about these songs, and is it some guilty pleasure I need to cast out?

MBM: Right. So what is it then, in looking at all these songs, and performing them and hearing others perform them, what do think . . . I mean obviously we’re listening to these tales of things gone wrong and someone dying. And yet they seem to be, like you’re saying, songs about real life, about real things, about real people. And if there’s this tradition of a performer just speaking to the audience about their shared lives, what do you think the murder ballads speak to us about? What are they telling us?

JL: Well, death and loss and passions. You know? There’s a lot of songs about dying, bluegrass has a lot of songs about Mother dying and going to heaven. There’s a lot of songs in the folk tradition about disasters. There’s an almost journalistic element to it, in a song like “The Trimdon Grange Explosion.” Sold millions in sheet music and it’s all just about naming the people who died down in the coal mines, it’s a fantastic song. But really heavy.

JL: I just think people, that’s possibly something that’s coming from the bottom up. It’s something that people are interested in a very basic, grassroots level. It’s not pretty pop music made by some clever gentleman in Tin Pan Alley. It’s kind of the opposite of that. And I found a lot of parallels with that and punk, the harshness and nihilism in punk. It was definitely unpalatable subject matter, to sing about things that may be difficult, that people don’t want to do, are fascinated by, but would not want to hear all the time in their daily lives.

MBM: It’s a way of sort of having your cake and eating it too. You can acknowledge your murderous impulses, that connect us all, but maybe not pick up the knife . . .

JL: Yeah, well Rennie Sparks (of band The Handsome Family) wrote a little essay when we were doing that (The Executioner’s Last Songs) and she wrote some stuff about songs being like dreams. It’s kind of unthinkable, the idea of killing someone. Or the feelings of someone, of remorse, they’d be feeling after it happened and knowing their punishment was coming. And the song gives you a chance to kind of like get inside that. It’s fascinating.

MBM: Have you written a murder ballad?

JL: Em . . . probably. Not consciously! (laughs).

MBM: Okay. Shame on us both for not knowing!

JL: I’d have to sit and think about that. Yeah, I don’t know. The album I did with The Sadies, there’s a couple of things that sort of allude to someone trying to kill someone (laughs). There’s a song called “Drugstore”, somebody appears in a dance hall with a gun. But I don’t think anyone get’s shot. I think they kind of run off (laughs).

MBM: That’s unusual. Because usually if there’s a gun it has to go off.

JL: Yeah, yeah. I think “It looks like that big clown has a gun” is the line. But again I’d have to go through . . .

MBM: Do you want to write one?

JL: I don’t know. I don’t know if there’s a real role for me to write one. My son just wrote a song called “Kill Rahm” for his band. “Kill kill kill die die die Mayor Mayor Mayor Rahm.”

MBM: Oh my gosh. What’s his band’s name?

JL: The UnGnomes

MBM: They’ll be known soon if they go out in public with that song.

JL: No, the Un-Gnomes. Like in the garden. But that doesn’t particularly stand out in their set because everything else is just as kind of incendiary. They’ve got a new song called “Fuck Old People” (laughs) which I quite like. From my point of view I was like “Whaddya mean, make love with seniors citizens?” And he’s like “NO, Dad!” (laughs). What a wonderful sentiment!

MBM: (laughs) How generous of you, you young whippersnapper! Well, thank you, Jon.

JL: Okay, is that enough?

MBM: Yes, I think so.