He Had It Coming

|

| Wilmoth Houdini |

As a rough estimate, Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Jordan’s performance of “Stone Cold Dead in the Market,” which we introduced in the previous post, appeared at the half-way point in the song’s career thus far. The song originated as a folk song in Barbados as “Payne Dead” or “Murder in the Market” in the 1870s. The original versions contain a number of personal names and some references that suggest they are based on a true story. So, the song may well be a true murder ballad in a more narrowly defined sense than its popular successor “Stone Cold Dead in the Market.”

There is some excellent scholarship out there on this song. My plan is not to recapitulate it so much as to provide a soundtrack for some of it, add a few musical finds and thoughts of my own, and relate this song to our broader discussion. For more detail, Franklin Bruno’s article is a very good start.

Payne Dead

The only example I can currently find of “Payne Dead” is this small fragment (30 seconds), from Ethel McIntosh in a field recording collected in 1980 on St. Croix (per Bruno). At this point, the song is probably over a century old, so even with this short fragment, it’s difficult to determine how much resemblance it might have to the original.

Murder in de Market

We may have better luck in turning to “Murder in de Market,” which seems closer to the version that traveled from Barbados with Caribbean sailors and became popular in Trinidad and the Panama Canal Zone around 1910. Both “Payne Dead” and “Murder in de Market” include proper names of people, and some indication of geography, which are both absent from most versions of “Stone Cold Dead.”

Here is one representative set of lyrics for this version, included in Robert Springer’s Nobody Knows Where the Blues Came From: Lyrics and History.

Murder in de market murder! (x3)

Hide me, oh Miss Clark, do hide me.

Put me under de bed an you hide me

Hide me, oh Miss Clark, do hide me. (x3)

Betsy, tell me what you do before I hide you (x2)

I went to the market to get beef,

Payne call me a liar an I stab ‘im.

Payne dead, Payne dead, Payne dead. (x3)

An I wish Grand Session was tomorra.

I would answer de judge like a lion, (x3)

For I ain’t killed nobody but me husband.

Didn’t mean to kill him but him stone dead. (x3)

Payne call me a liar an I stab ‘im (x2)

|

| Sir Willard White. OM, CBE |

From this original, the reason for the murder and the means of accomplishing it change. In the later Fitzgerald/Jordan version, the “Betsy” character kills her abusive husband in self-defense with some combination of blunt kitchen instruments. Above, Betsy stabs Payne to death for calling her a liar. It’s a little spare in detail otherwise, encouraging us to fill in the gaps. What did he accuse her of lying about? We now have grounds for suspicion about jealousy or allegations of infidelity. In any event, our heroine’s self-defense case is certainly weakened. My guess is that the changes to the “self-defense” version were key in broadening the appeal of the calypso tune that Fitzgerald and Jordan took up.

Here’s an operatic version of “Murder in the Market” by Jamaican-born bass baritone, Willard White. The lyrics don’t line up precisely with the above, but it keeps the references to particular people. Betsy Thomas is our “culprit.” Sir Willard is decorously silent on her means and motives.

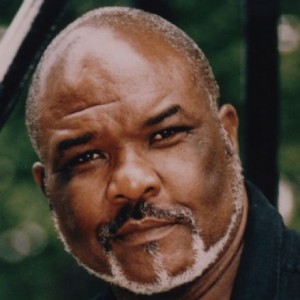

He Had It Coming

As you may remember from the Decca record image in the previous post, the Fitzgerald and Jordan version credits Wilmoth Houdini as the songwriter for their version of “Stone Cold Dead in the Market.” Despite the different titles, the versions are quite similar, and credit to Houdini, at least to this extent, was due.

Fitzgerald and Jordan’s version was a hit in the spring of 1946. At the end of that year, folklorist Alan Lomax organized a calypso concert, “Calypso at Midnight” at Town Hall in New York City. In this concert, Macbeth the Great presents his version of “Stone Cold Dead in the Market,” re-introducing some details from the original “Payne Dead”/”Murder in the Market.” Bruno suggests that this was a “mild rebuke to [Houdini’s] claims of authorship.”

You can also hear the recording at the Association for Cultural Equity’s Alan Lomax archive here. The recording notes at that site clarify Bruno’s comment about the claims of authorship, stating “[The song] was first recorded by Louisa Neptune and three other women on July 15, 1939 (‘Payne Dead, Payne Dead — Quadrille’), in Toco village, Trinidad, collected by Melville and Frances Herkovits. On September 11 that same year, Wilmoth Houdini cut the first commercial recording and registered the copyright.”

|

| Macbeth the Great (on the left) |

So, it appears that Houdini’s magic trick was to copyright a folk song for himself. I guess somebody had to do it.

After Ella

A number of artists took up the song after Fitzgerald and Jordan. Some capitalized right away on its initial success. Some brought it back years later as a revival or a novelty piece. None of them were as successful as the Fitzgerald and Jordan piece, which, as we discussed in the last post, may have had the advantage of some good timing, sociologically speaking.

The King Sisters, with Billy May and His Orchestra, take calypso into close-harmony, big band swing, modulating the tune a bit along the way. They display an ambivalent relationship to the song’s West Indian dialect. Bruno places this song as part of a 50s or 60s revival, but other sources suggest that it was released in 1946 as the flip side to “The Coffee Song.”

If that performance seems somewhat less than authentic to you, where else can we turn? Oh, perhaps here. Pat Boone, of course! Boone put out a revival version in the early 1960s… (I’m not sure what to make of this YouTube video. There are a couple of odd shots of Boone in the shower. You’ve been advised.)

For a post 40s version with some authentic Latin folk flavor to it, the Santino Ellis recording, with it’s accelerating intensity is one of my preferred versions. Smithsonian Folkways lists this recording as being made in Nicaragua in 1957.

Poet, memoirist, and “Global Renaissance Woman,” Maya Angelou had a career as a nightclub singer before rising to greater prominence in literature. “Stone Cold Dead in the Market” appears on her 1957 album Miss Calypso.

Whodunnit?

Before wrapping up, I want to include two more versions for the lyrical variations they introduce. In most of the versions we’ve heard so far, the perspective of the singer is that of “Betsy” or the woman defending herself from her drunk, abusive husband. If the singer of the song was not female, he was either content to sing it in the first person as the woman or a third person reporter. The next two versions take different tacks, one with smoother sailing than the other.

Trinidadian musician Edmundo Ros introduces a new, unnamed character, which makes a big difference to how we might interpret the song. The basic narrative is the same, but the third character is one who intervenes to defend “Betsy” from her husband. As we learned in the last post, in real life, intervening in marital violence was rather rare, at least in the U.S. (Pinker’s book suggests that things would likely not be much better in most other countries.) So this is an interesting twist. It also invites the listener to fill in the gaps about what the protagonist/narrator’s relationship to “Betsy” was prior to this incident. (As an added bonus, there’s a rather humorous, but appropriate, instrumental homage at the very end.)

One final twist is in the version produced by the Leeds, England-based West Indian band The Bedrocks. Here, the song is told entirely in the voice of the husband, who goes out drinking and upon his return is beaten by his wife. He takes up the rolling pin, pot, and/or frying pan, and subsequently explains “I killed nobody but my woman.” Despite its upbeat ska rhythm and acknowledging that the song explains that she was beating him, I find this version creepy. Double-standard, perhaps, but it’s reasonable to think that one of the reasons that we find the female-centric version more palatable is that we suppose that women often had or have a lot less freedom to escape abusive relationships. This detail of exactly who started it seems generally irrelevant in light of this singer’s rather buoyant refrain. He doesn’t generate a lot of sympathy.

Conclusion

So, we have a few twists and turns along the way, as the song dances somewhere at the intersection of novelty and danger, of murder and tropical sunshine. In some sense, if there’s anything serious to be taken away from the song, it’s that it appears to serve as one small musical tool in a broader cultural renegotiation of gender roles. And, if it fits within the broader murder ballad tradition, it probably does so best as a precursor to more serious treatments of these themes in those murder songs of the late 20th century and beyond which are informed by the advances in feminism in the last 50 years. In that sense, although “Stone Cold Dead in the Market” and its precursors and successors tap into some of the broader themes we often discuss here, they also have opened up another theme or two, and have taken us into new territory, musically speaking. I fully expect both developments will continue.

Thanks again for reading.