Harris and the Mare

With Pancho having met his match in the deserts down in Mexico, this week we turn to the north country, and an Ontario mill town, and a song inspired by a story overheard in a bar. Stan Rogers, penned “Harris and the Mare” a little over 30 years ago. The song is formally a balllad, for what it’s worth, but I’ll need your help again to let me know just how far we stretch the definition of “murder ballad” with this song–that is, whether there’s a murder here, legally or psychologically.

|

| Stan Rogers (1949-1983) |

For those of you unfamiliar with the work of Stan Rogers, he was a gifted songwriter and a musical chronicler of the life of Canadian people–writing songs of working people from the Maritimes to the Canadian prairie. He died too young, in an airplane fire, just as his career was stepping to another level.

“Harris and the Mare,” was expanded into a radioplay for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) in 1982. (Incidentally, the radioplay premiered 30 years ago today, on April 9, 1982.) We’ll focus on the radio play in the next post. In a post or two later this week, we’ll listen to some songs by others that explore some of the same terrain as “Harris and the Mare”; where the songs’ protagonists come to terms with the violence they have been driven, by powers internal or external, to inflict. To set the theme today, we’ll take up the question of the nature of the “crime” here, if any; and how, as with other murder ballads, the “perpetrator” relates to their friends and community after an episode of violence.

“Harris and the Mare” by Stan Rogers (Spotify)

The other comment from Rogers I’ve found on this song is in the liner notes to Between the Breaks…Live!. He writes, “Somebody once said, ‘Never threaten a little man. He’ll kill you.’ No matter how much of us believes that violent conflict is to be avoided at all cost, there are some things that must be fought for. Even the most timid person can be brought to stand up for a belief.”

For the record, I find Rogers’s second explanation unsatisfactory–not that it matters for my enjoyment of the song. As was clearly the case with “Pancho and Lefty,” it’s difficult to pin a song down to a particular reading. Nevertheless, I think there are some interesting ways to question Rogers’s short synopsis of his own work.

|

| Mike Tyson |

The first is to ask whether anything approaching a “belief” is stood up for in the action of this short drama. The song establishes our protagonist’s credentials as both an interpersonal and a political pacifist–he abstains from personal violence, doesn’t keep company with the violent, and was a conscientious objector to the war (in this case, the Great War, World War I).

“Night Guard,” by Stan Rogers (Spotify) (Lyrics here, mostly–what the site doesn’t show is that Rogers changes the last line of the refrain at the end to say “…now he’s doing time pulling night guard.”)

Your answers to how these songs differ or resemble one another will probably depend on how you fill in the gaps in each–what happens to these characters between the lines and before the songs begin. Both act in self-defense, at least to a degree, but one with deliberation, the other not.

As I suggest above, what I think is interesting about “Harris and the Mare” is that the protagonist is left in a situation of having to reconcile his beliefs and his actions after he has acted on impulse or instinct–and an instinct probably as much or more related to revenge as it was related to self-defense. Secondarily, he is also coming to terms with his self-defense leaving his assailant, Clary, dead. Although, this he doesn’t seem as remorseful about.

Outcast

It is clear from the concluding verses of the song that Clary’s death is itself not as much a source of anguish for our protagonist as that sudden surprise at being driven to violence, on the one hand, and is his separation from the community on the other. It’s actually this aspect of the song that made the stronger case for me for this song as a murder ballad. As with the guilty (John Lewis), or the semi-guilty (the fictional Pancho), so the not guilty (like, perhaps the real Frankie Baker) also find themselves pushed to the outside of their community because of their actions. I’ll dig into this a bit more in the next post as well, as the radio play puts a bit more meat on the bones of this question, and it’s difficult for me to get back to my original point of view.

In any event, for years, when I listened to the song, I always perceived that the horror of the scene had made our protagonists’ outcasts–that something about the sordidness, or the violence, or the bystanders’ own cowardice at the prospect of intervening and staying the hand of the drunken Clary, had separated them from our protagonist/narrator. In the process of the protagonist’s declarations about it, and in his bitterness, it sounded like a good riddance. Again, how this gets interpreted is idiosyncratic to the listener. The inflection changes a bit in the interpretation we take up in the next post.

|

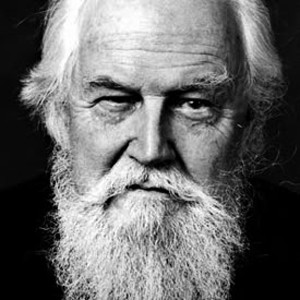

| Robertson Davies (1913-1995) |

While we’re with the Canadians, though, I’m reminded of the late Canadian author Robertson Davies, who maintained that there were really only about fifteen or so core stories in the repertoire of human story-telling, and that most of what we have in literature represents variations on that limited set of core themes. I can’t find the citation at the moment, but if you’re familiar with Davies’s work, you’ll recall his affinity for Jungian archetypes. It’s of a piece with that.

In any event, in preparing to discuss this song, I kept thinking that I had seen the scene before, but I had trouble pinning it down. At first, I thought it was West Side Story, but that wasn’t it.

It was Oklahoma! –the concluding scenes. There may be other similar stories, and if you can think of any, please comment below. If Davies’s theory is borne out, and this is somehow one of the core group of stories, we may be able to pull together another post of stories for comparison.

|

| Hugh Jackman |

With Oklahoma!, we have another illuminating contrast about killing in self-defense, and how a community comes to terms with it. In the video clip below of the 1998 revival production in London’s West End, you’ll see Curly, portrayed by Hugh Jackman, defend his honor and the honor of his new bride from the assaults of a drunken Jud Fry. But, as you’ll see, Oklahoma! is essentially a musical comedy (stylistically speaking), and “Harris and the Mare,” is a murder ballad, and a tragedy.

[I post this with some hesitation, as I fear that linking a video depicting a fist-fighting, bare-chested Hugh Jackman might be misleading, attracting the “wrong” element to our humble and serious blog. I, for my own part, was thinking at first that Jud was mighty lucky that Curly didn’t break out the adamantium claws. Don’t worry, gentle reader, I’ll be sure to refrain from cynical and manipulative search engine optimization tricks…]

More seriously, though, there are obviously spoilers here, so if you haven’t seen Oklahoma! and want to see the whole thing from the beginning, you can start here.

The fighting begins after the 6:30 mark:

The community resolves the dilemma of having a killer in their midst here:

In some sense, the contrast between Oklahoma! (at least as plucked out of context) and “Harris and the Mare” may say more about genre (comedy vs. tragedy, musical theatre vs. murder ballad) than it actually tells us about the social circumstances surrounding violence itself, but it is clear that violence within the community demands a decision about how its perpetrators may subsequently relate to that community. The characters in the musical seem driven by a need to give Curly’s actions some definitive and authoritative interpretation–to make having a killer in their midst acceptable. They put him on trial.

In “Harris and the Mare,” whether because of the actions in the bar or actions prior to the narrative of the song, the neighbors do not feel obligated to assist our wounded protagonist and his wife. They essentially remove the killer from their midst by their inaction. It is the sense of exile our protagonist feels that pushes this song into the territory of murder ballad for me–but a variety wherein the listener’s empathy for the killer is different because of the circumstances of his act.

Next up

As I mentioned earlier, we’ll go to the radioplay version of “Harris and the Mare” next, which shades and deepens a few things in ways I have resisted here. The song came first, and is worth taking on its own terms. I’ve done my best to separate them as distinct works, but do somewhat wish I had finished this post before listening to the radioplay. More to come on that later. And, I’ll add a post or two later this week of other songs reckoning with the internal and external costs to the individual of being pulled into acts of violence (the organized violence of war or otherwise). Stay tuned.

Disclaimer

The decision to discuss “Harris and the Mare” this week was completely unrelated to any particular items in the news. As more of an Arts and Humanities blog, we are most interested in discussing things, specifically music, that help unfold aspects of human experience generally; but I have avoided deploying my contributions to the blog to comment on particular matters of controversy in the news. We may or may not keep doing so as our discussions evolve, and I’m speaking mainly for myself at the moment, but wanted to add a disclaimer here.

Readers outside the U.S. may or may not be aware of an on-going news story in the U.S. that involves issues related to claims of self-defense. Nothing in this post is intended to be a direct comment on that case, or to imply a particular position on it. I have a few opinions about the matter, but I don’t plan to offer them here. Whether or not your opinions about it jibe with mine, if anything above helps you refine your perspective one way or the other on any matters you hear, read, and/or decide about, I’m grateful for that.