Digging for Clues in the Fatal Flower Garden

“Fatal Flower Garden,” recorded in 1929 by Nelstone’s Hawaiians, is only the second of eighty-four songs on Harry Smith’s epochal Anthology of American Folk Music – a collection justly celebrated in some macabre corners (mine, for instance) for its songs of dark, outré subject matter and tone (e.g., Clarence Ashley’s “House Carpenter,” G. B. Grayson’s “Ommie Wise,” Dock Boggs’s “Sugar Baby”). But despite such robust competition from the remaining eighty-three, for me it has always been the creepiest – the darkest, most outré of them all.

“Fatal Flower Garden,” recorded in 1929 by Nelstone’s Hawaiians, is only the second of eighty-four songs on Harry Smith’s epochal Anthology of American Folk Music – a collection justly celebrated in some macabre corners (mine, for instance) for its songs of dark, outré subject matter and tone (e.g., Clarence Ashley’s “House Carpenter,” G. B. Grayson’s “Ommie Wise,” Dock Boggs’s “Sugar Baby”). But despite such robust competition from the remaining eighty-three, for me it has always been the creepiest – the darkest, most outré of them all.

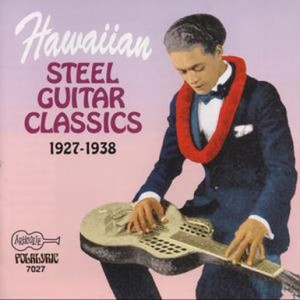

Its provenance is unspectacular: one of eight known sides recorded by the obscure Alabama duo of Hubert Nelson and James D. Touchstone – their performing moniker a reference to their (then quite trendy) “Hawaiian” sound (basically hillbilly music plus lap steel guitar) combined with their hybridized surnames – and entirely unlike the comparatively up-tempo other seven (the best known of which, “Just Because,” is a country standard famously covered by Elvis). The song’s surface eeriness arises from a discordant union of opposites – specifically, its incongruous blend of soothing “island” music and relaxed “folksy” singing with a lyric that describes (of all things) ritual child murder.

Or more accurately, almost describes …

More on that in a moment – but first, let’s consider the song:

Above …

It starts quietly, almost preternaturally so, and never varies in tempo or dynamics. Just a steady rhythm guitar strumming beats 2 and 3 in brisk but subdued waltz time while a steel guitar mutedly picks the song’s tune. Then voices join in – two men in close harmony, Southerners, drawling its verses in an unhurried manner that might sound lazy or sleepy if not for the slight lilt they give to every other syllable.

It rained, it poured, it rained so hard,

It rained so hard all day

That all the boys in our school

Came out to toss and play.

They tossed their ball again so high,

Then again so low,

They tossed it into a flower garden

Where no one was allowed to go.

The voices are gentle and childlike – grown men reciting a nursery rhyme. Appropriate, perhaps, for a nostalgic evocation of child’s play on a rainy afternoon (and if you let it, the scratchy background noise of the 78 RPM source recording resembles rainfall), but as the verses get stranger the voices remain unchanged, and their sing-songy tone grows unsettling.

Up stepped this gypsy lady,

All dressed in yellow and green;

“Come in, come in, my pretty little boy,

And get your ball again.”

“I won’t come in, I shan’t come in,

Without my playmates all;

I’ll go to my father and tell him about it –

That’ll cause tears to fall.”

She first showed him an apple sweet,

Then again a gold ring,

Then she showed him a diamond,

That enticed him in.

Next, a short instrumental break: a “Hawaiian” retread of the verse’s melody (the song’s invariant structure – verse after verse without chorus, refrain, or change of tune, key, or rhythm – creates a hypnotic effect that complements the chant-like singing), the Pacific Island ambiance increasing the song’s strangeness. Then, a sudden turn of the screw:

She took him by his lily-white hand,

She led him through the hall,

She put him into an upper room,

Where no one could hear him call.

Or in modern horror movie parlance, “where no one can hear you scream.” Without elaboration or explanation, the narrative shifts from omniscient to first person:

“Oh take these finger-rings off of my fingers,

Smoke them with your breath;

If any of my friends should call for me,

Tell them that I’m at rest.”

“Bury the Bible at my head,

The testament at my feet;

If my dear mother should call for me,

Tell her that I’m asleep.”

“Bury the Bible at my feet,

The testament at my head;

If my dear father should call for me,

Tell him that I am dead.”

The End. A tasteful glissando on the steel guitar and we’re done. The rain-like white noise ceases less than three minutes after it started. And if you’re like me, your neck hair is raised; your mind left swimming with the song’s haunting, fragmented imagery.