Cold Rain and Snow – Introduction

I first heard our subject ballad for the week from the same source I’m sure the majority of people who know it today did – the Grateful Dead. It had been part of their repertoire since their start in 1965, and by the time I was going to Dead shows in the mid-Eighties and on through to 1995, “Cold Rain and Snow” was a set opener or an early first set fire-starter upon which Jerry and the Boys could invariably rely for combustion.

We saw one example already in an earlier post of mine, which opened one of the best shows I saw after Brent Mydland died in 1990, and that most certainly illustrates my observation. (I’ll include the other examples from my original post as well below it.)

“Cold Rain and Snow” (1) Studio version -1967 (2) Live – 9/28/76 Lyrics as sung by the Dead

Now, I didn’t embark on this week’s treatment of the ballad with the Grateful Dead in mind, other than to cite them as the origin of my quest. All those years ago, when I discovered that the Dead didn’t write the song, I began to wonder who did. To make a long story short, I think we can know more or less, and the answer puts us here in our comfortably uncomfortable American murder ballad place. If you can’t wait, or came here for a quick Google answer to the question, skip down to Berzilla Wallin’s quote just above the Coda.

But I like long stories long. So if you do as well, I promise I’ll try to keep you entertained. I can’t deliver brevity, as the roots of this chillingly violent little ballad are deep in earth that took awhile to dig. I did uncover some (if not *the*) truth though, if there is such a thing in folk music. So, if you want, grab a shovel and come along. If you don’t have one, the awful man at the heart of this ballad said you can take his – though it’s slightly used.

“I married me a wife, she give me trouble all my life…”

In all versions I’ve found, the song starts with these lyrics or something very similar, and it all goes downhill from there. Don’t get me wrong – the story is engaging and the lyrics are as keen as the little pen knife the brown girl used to do in Fair Ellender – by “downhill” I mean how this sad tale ends.

After the opening lyric, every version of the song I know includes some close approximation of the line that gives it its title – “She ran me out in the cold rain and snow.” The rest of the song usually goes on to list the unnamed man’s additional grievances; and though the list is relatively short, the resolution is extreme. Most versions, but notably not the Grateful Dead’s, make explicit that the man kills his wife. Some versions make it more gruesome than others.

He just can’t take it any more, and so this weak man finds the strength to solve his problem with murder. So far in this blog we’ve seen men killing women for all sorts of awful reasons, but here we have a murder simply because the man feels ill-treated. (Wait, maybe his name was Frank.)

I addressed in the post linked above why the Grateful Dead may have left the murder out of this murder ballad. While it may seem counter-intuitive to those of us who deeply feel the resonance of murder ballads, the Dead’s non-lethal interpretation worked for them for thirty years – it was the only song in their repertoire that they performed consistently during their entire career. But without the murder (and leaving aside the power of the Dead’s musical treatment as it evolved) it becomes a baby booming boy’s lament – the sad tale of a man trapped in a loveless marriage, or of one who loves a domineering woman. Now, hippies taking the violence out of a murder ballad, and otherwise implicitly challenging the institution of marriage, is nothing earth-shattering – even if they do it quite well.

I addressed in the post linked above why the Grateful Dead may have left the murder out of this murder ballad. While it may seem counter-intuitive to those of us who deeply feel the resonance of murder ballads, the Dead’s non-lethal interpretation worked for them for thirty years – it was the only song in their repertoire that they performed consistently during their entire career. But without the murder (and leaving aside the power of the Dead’s musical treatment as it evolved) it becomes a baby booming boy’s lament – the sad tale of a man trapped in a loveless marriage, or of one who loves a domineering woman. Now, hippies taking the violence out of a murder ballad, and otherwise implicitly challenging the institution of marriage, is nothing earth-shattering – even if they do it quite well.

But tracing the ballad back from the Grateful Dead, and looking at its incarnations today, might give us a little bit of a rattle – particularly when we find that many female artists play the *hell* out of this seemingly misogynistic ballad today. But I’ll take that point up in a later post this week, where we’ll see quite a few contemporary covers of this little dagger of a song. For now, shovels at the ready…

A folk song from “The Three Laurels”

In the liner notes for The Music Never Stopped: The Roots of the Grateful Dead, Blair Jackson speculates that the inspiration for the Dead’s version of the ballad was Obray Ramsey‘s cover on his 1963 album Obray Ramsey Sings Folksongs From the Three Laurels. This certainly makes sense, as Ramsey’s recording of the song was, as far as I can tell, the first commercially available. However, in a comment made on this post after publication, Ken Frankel claims that he taught the ballad to Jerry Garcia in California after a musical road trip through the South, during which Frankel learned the ballad directly from Ramsey! The Grateful Dead debuted in 1965 with this as one of their primal songs, and the musicians were deeply connected to folk music and certainly would have heard Ramsey’s album, popular as it was in such circles. However, to know Ken’s bit of the story means that the ballad first made it to the West Coast directly through a musician passing it along in what was essentially the oral tradition.

For us, though, we need the recording. Let’s hear from Obray Ramsey then.

“Rain and Snow” – Obray Ramsey (Spotify) Lyrics for Obray Ramsey’s version

Jackson also posits in those liner notes that the ballad is “apparently one of those ageless songs that came down through many generations from some undetermined English folk lineage.” I believe in this he is all but certainly not correct.

The only evidence he articulates for this claim is the existence of the British folk band Pentangle‘s version. As well, Ramsey’s folk pedigree as one of the old-time singers of Madison County, North Carolina (perhaps the place where the British ballads in their authentic context survived the best in America, where the waters of the Big Laurel, Little Laurel and Shelton Laurel rivers run) presumably plays implicitly into Jackson’s claim of an old English origin for the song.

But that’s all putting the cart before the horse. Check out Pentangle’s version before I argue, and note that we’ll come back to it later this week.

But that’s all putting the cart before the horse. Check out Pentangle’s version before I argue, and note that we’ll come back to it later this week.

“Rain and Snow” – Pentangle (Spotify)

Lyrics for Pentangle’s version

This performance, while truly outstanding, proves nothing of the ballad’s origins. Pentangle cut their cover in 1971, well after Ramsey and the Dead both brought the song to modern audiences. More convincingly, while Pentangle’s lyrics aren’t *precisely* those of either, where they don’t follow those versions they add lyrics that are quite clearly American.

“I ain’t got no use for your red apple juice” is a line I have yet to see in a traditional British ballad. It is, however, not unknown in American ‘white blues’ and likely has its origin in the African-American tradition. As well, the lyric where he sees his wife “in the shade counting every dime I’ve made” suggests America as well, at least as far as a reference to currency can take us.

And, lo and behold, both lines are present in Dock Boggs‘ ‘white blues’ recording “Sugar Baby“! (Dock was influenced powerfully as a boy by African-American music in the Appalachian coal country a full century ago.)

Given all this, and the fact that Pentangle are also playing the *sitar* as one of the key instruments in the performance and the song is obviously not from India, I think it much more likely that the experimental musicians that made up that band in 1971 were fusing multiple cross-cultural elements, rather than being perseverators with regards to some ancient British ballad.

If it’s not British, it’s…?

Still, just because Pentangle’s version doesn’t reveal British origins does not mean they aren’t there. Indeed though, there is evidence that strongly suggests this song is essentially American – and has its origin in western North Carolina after the Civil War.

Consider for one that the ballad is widely covered today, but that these covers admit of little lyric or melodic variation. This suggests a ‘bottleneck’ of source material, perhaps even only one direct ancestor, rather than the usual (and sometimes overwhelming) variety we see with true British ballads. That’s not enough evidence on its own, but it is telling.

Now, several links have been suggested to songs like “The Sporting Bachelors” (here’s Grayson and Whittier’s track, and lyrics) and the “Red Apple Juice”/”Sugar Baby” group of songs cited above. Some even look to songs like “Payday” (here’s Mississippi John Hurt’s version, and lyrics) because of the common theme and similarity of certain lyrics.

I think there’s something useful in these comparisons, to which I’ll return below – first though, consider that being mad at your spouse is not a rare theme in anglophone folk music. As well, rhyming ‘wife’ with ‘life’ isn’t a literary stretch, and one would expect to see it often in totally unrelated songs. For example, Josiah Combs collected “The Married Man” in Knott County, Kentucky and published it in Folk-Songs du Midi des Etats-Unis in 1925. The first line is indeed “I married me a wife, she’s the plague of my life.” But the next line “I wish I was single again” puts it squarely in the male song group of “I Wish I Were Single Again“. (Here’s the female group info as well, and a clip to hear – there is murder in neither group of this song.)

“Sporting Bachelors” seems to come the closest lyrically to “Rain and Snow” – there are undeniable similarities. (You’ll see below a traditional performance that uses lyrics from both.) At least he wants her dead at the end, though he doesn’t kill her. But I find no evidence of that song in Britain, or even outside of the Appalachians – and it is probably not as old even as “Rain and Snow.” At best they may have been contemporary, perhaps even relying on some of the same artistic inspiration. Such may very well be true for all of these ‘connected’ songs.

What that inspiration might have been is beyond my ability to research at the moment, but I do have a gut feeling about it. I doubt it was one song, but rather a mixing of traditions.

As I hinted at in relation to Dock Boggs, the coal country of Appalachia at the turn of the 20th century received an influx of African-American (among other) immigrants to work the mines and in related industries. Indeed, the Civil War had already opened up these isolated areas to outside influences, and by 1900 the keepers of the British ballads in places like Madison County were regularly exposed to new musical styles and traditions. And it’s impossible to believe that Dock Boggs would have been the only white kid in Appalachia interested in black music. There as always in America, despite the racist social and political system, African-American and Anglo-American music joined together in many interesting ways. Remember “Swannanoa Tunnel“?

That means that connections to songs like “Payday” and “Sugar Baby” really do matter, though perhaps not in that ‘direct ancestor’ sort of way that we often talk about with British ballads. It may have been more dynamic than that, more about integration than perseveration. For example, check out Shorty Bob Parker’s blues, “Rain and Snow”, from the late 1930’s. Though this isn’t Ramsey’s source, he’s undeniably singing “you drove me out in the rain and snow.” That’s more than just coincidence, or so I believe. If we let go of the need to find a direct ancestor of one for the other, such songs as these in relation to our target “Rain and Snow” open up some interesting possibilities. If someone wrote a murder ballad in western North Carolina after the Civil War, there were melodic and lyric building blocks to use all over the place. Those building blocks would likely show up in all sorts of songs composed in the same decades. In another lifetime’s career, I’d spend a year charting it all out!

…an American original!

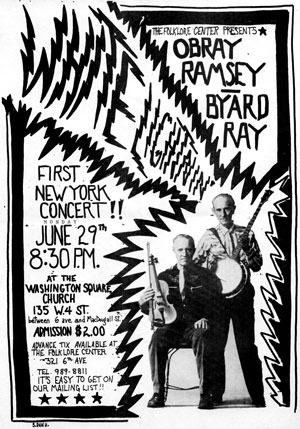

Concert Poster, The Folklore Center, ca. 1962

Ok. The song is not British, and the blues influence / interaction is a murky one to consider – so, can we pin anything else down about this song in America?

Yes.

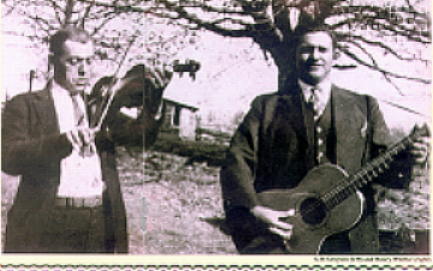

As mentioned above, Obray Ramsey was from Madison County, North Carolina. The musical tradition of that part of the country was and is one of our national treasures. Sheila Kay Adams, a master balladeer and storyteller, still makes her home there on her beloved Eskey’s Ridge and keeps the tradition alive. Her uncle, Byard Ray, was a cousin of Ramsey’s and performed with him some during the ‘folk revival’ of the early-1960s. Here’s a fascinating interview with Sheila where she talks about Madison County’s musical tradition and mentions Byard.

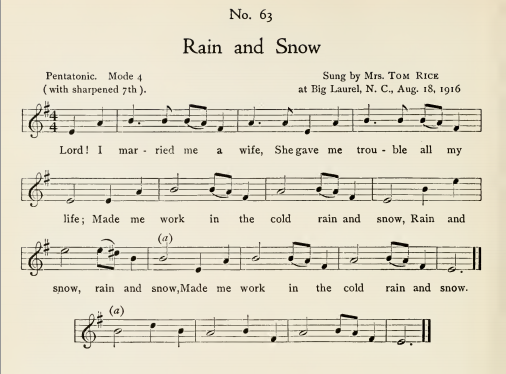

The earliest citation I can find of “Rain and Snow” is from Cecil Sharp‘s 1917 English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians. Now you’re tempted to say “Aha! See, it really is British! Even Cecil Sharp said so! Who are you, Mr. Amateur Murder Ballad Blogger, to argue with a legend in the field?” (Sorry, I’m having a Mudcat moment.)

Eh, not so fast. While Sharp’s book is certainly full of ballads we can easily trace back to Britain, he includes “Rain and Snow” with no evidence of its origin, and only a sliver of a verse.

And, it turns out, the little bit of information he does include really gets us back to square one – and in this case as you’ll see below, square one is certainly the home of The Three Laurels – Madison County. Check out Sharp’s entry for the ballad.

Do you see it? “Sung by Mrs. Tom Rice at Big Laurel, N.C. Aug. 18, 1916.” Folks, Big Laurel, North Carolina is in Madison County! So, we’ve seen no evidence that this song in the form we know it was ever collected outside of that one place. If someone can show me otherwise, I’ll be grateful. I’m no professional researcher, but I haven’t found it yet. Honestly, I don’t think you will either.

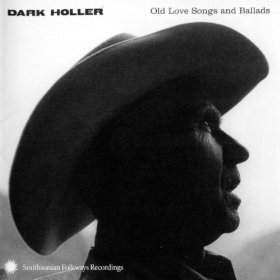

Why not? There’s a bit more. Of all the recordings I can find, 40 some so far in my Spotify playlist, there is actually one that is a bona fide folk performance by a traditional Appalachian ballad singer. And this version is *brutal* folks. Check out Dillard Chandler‘s “Cold Rain and Snow”, recorded in the field in 1965, the same year the Grateful Dead began playing in San Francisco, and released later in a compilation of music from him and his neighbors.

“Cold Rain and Snow” – Dillard Chandler (Spotify) Lyrics for Chandler’s version

Of all we’ll hear this week, none is as chilling as Chandler’s version. Here we’ve got motive, opportunity, and a horrible method. We even get to see the killer’s reaction after he does the deed. “I trembled to my knees with cold fear.”

“But,” you might say, “those lyrics are similar in certain places to “Sporting Bachelor.” Doesn’t that suggest that they both have a common ancestor?” Perhaps, but I don’t think so in this case. If anything, I would hazard a guess that Chandler, a traditional singer, by the early 1960’s may have fixed other compatible lyrics on to this older ballad – perhaps more likely, that he learned it from someone who had done so, or maybe even that such lines were originally part of both songs, being cooked up in the same post Civil War Appalachian ballad stew.

Anyway, you people who are truly folked up already know what’s coming. It’s old news to you, but I’m not sure how well our younger folks know this yet. Dillard Chandler was born, lived, and died in… wait for it… Madison County, North Carolina. When Cecil Sharp came through during World War I to find British ballads in Appalachia, many of the folks singing for him were Chandler’s immediate family. He learned “Rain and Snow” in the mountains where it was born.

Anyway, you people who are truly folked up already know what’s coming. It’s old news to you, but I’m not sure how well our younger folks know this yet. Dillard Chandler was born, lived, and died in… wait for it… Madison County, North Carolina. When Cecil Sharp came through during World War I to find British ballads in Appalachia, many of the folks singing for him were Chandler’s immediate family. He learned “Rain and Snow” in the mountains where it was born.

If you check out the liner notes written by John Cohen to the compilation album that includes this track, you’ll find the answer that’s the end of our line. “Rain and Snow” was a ballad written about a murder that actually happened in Madison County, probably in the 1870’s. Cohen quotes Berzilla Wallin (who lovingly taught Sheila Kay Adams many of the old ballads) on its source.

“Well, I learned it from an old lady which says she was at the hanging of – which was supposed to be the hanging, but they didn’t hang him. They give him 99 long years for the killing of his wife… I heard the song from her in 1911. She was in her 50’s at that time. It did happen in her girlhood… when she was a young girl… She lived right here around in Madison County. It happened here between Marshall and Burnsville; that’s where they did their hanging at that time – at Burnsville, North Carolina. That’s all I know, except they didn’t hang the man.”

A true story then. But, like me, you probably figured that all along. It’s just too real and awful to be otherwise.

Coda

So, we can ask as we always do why someone might turn the story of a true, gruesome murder into a ballad like this. If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you know that such a question leads to several different places.

In my second post later this week, I will spend most of my time looking at contemporary recordings of this ballad, and in doing so will contrast those that are in men’s and women’s voices. I don’t know that I’ll have a solid answer for you as to why women love to sing this ballad and do it so well, but I think I’ve got an idea. I think it has something to do with why this song was written in the first place.

Thanks for sticking with me this long, and I hope you join me later this week if you’re up for it.