BOB DYLAN and THE BAND: The Basement Tapes Complete: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 11

Bob Dylan and The Band

The Basement Tapes Complete: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 11

Columbia Legacy 888750 161222

A legend in their time, Bob Dylan’s basement tapes were informal sessions recorded on three sites (one a basement) between March 1967 and February 1968 after he disappeared to upstate New York to recover from a motorcycle accident, retrench with his family and avoid hordes of fans who’d make him their guru or leader – roles he shunned. “Don’t follow leaders,” he’d already warned.

His sidemen were the Hawks, who’d previously backed Ronnie Hawkins in Toronto. Soon they’d morph into the Band, taking rock and roll back to the fertile soil from which it sprang. Dylan wrote “Tears of Rage” and “This Wheel’s on Fire” with them.

Lo and behold, in 1969 some tracks emerged on seriously lo-fi unauthorized bootlegs starting with Great White Wonder. Eventually – in 1975 – his label, Columbia, released two-LP, 24-song The Basement Tapes. Much more lingered in storage.

“The tapes are proving to be the Rosetta Stone of American music,” say the notes to 138-track The Basement Tapes Complete. “Their non-release gave them a Greta Garbo air of mystery.” So what are they? Moments of puzzling brilliance. Experiments, goof-offs, spontaneous laughter, false starts and song fragments. Traditional folk ballads and teen-oriented ’50s rock classics that young Robert Allen Zimmerman cut his teeth on back in Minnesota. “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” advised, “Strap yourself to a tree with roots.” Musically speaking, he’s showing us his tree’s roots. For example, his “Next Time on the Highway” on disc 6 draws on disc 5’s trad “Ain’t No More Cane” (AKA “No More Cane on the Brazos”).

The first two discs in particular seem like an unpolished Self Portrait for all their covers of folks like Johnny Cash, Utah Phillips, John Lee Hooker and Curtis Mayfield. A surprising number of songs were previously recorded by (some penned by) Ian & Sylvia. In general, he delivers his own compositions with more conviction than he gives the others. The heartbreak Hank Williams brought to “You Win Again” isn’t here.

Often the joker, he turns Bill Haley and the Comets’ “See You Later, Alligator” into “See You Later, Allen Ginsberg” including a rousing “See you later, crocodator!” Sonny Knight’s tender 1956 hit “Confidential” is reworded “Your love for you will always be confidential to me.” For comic egotistical bravura, his own “I’m Your Teenage Prayer” spoofs teen romance songs with a Band member ad libbing, “I’m your teenage hair.” He sings of a one-room Cadillac on blues/jazz rap “What’s It Gonna Be When It Comes Up.”

“Blowin’ in the Wind” and “One Too Many Mornings” are revisited with arrangements that seem incongruous considering their words. Of course, Dylan – the prince of dadaism, the Salvador Dali of songwriting – has never shied from incongruity.

The box gives up to three takes of some of the best songs. We get the “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” first introduced to us by the Byrds on 1968’s Sweetheart of the Rodeo, later reappearing on Dylan’s 1975 Basement album. Now we’re also treated to a variant with vastly different words (“Look here, you bunch of basement noise.”). That’s the version on the well-chosen 38-song, two-CD (or three-LP) abridgment The Basement Tapes: Raw: The Bootleg Series Vol. 11 that Dylan fans without unlimited record budgets can choose instead of the deluxe box. (“Million Dollar Bash,” “Open the Door, Homer,” “Too Much of Nothing” and “Lo and Behold!” are among its songs.)

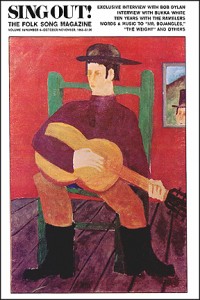

Among the box’s treats is its packaging using the 8”x8” dimensions of a vintage reel-to-reel tape box. The discs are housed in one hardbound book’s replicas of the original tapes’ boxes complete with tapes’ song lists. A second hardbound book’s illustrations galore include unused images from Nashville Skyline‘s and the ’75 album’s photo shoots plus 45-RPM disc picture sleeves of Miriam Makeba’s, Manfred Mann’s and Peter, Paul and Mary’s (plus many other acts’ ) covers of basement songs. We see Dylan’s paintings: his cover for the Band’s debut LP and the one he gave Sing Out! for the cover of its November/December 1968 issue, whose lead story was an interview with this man who rarely gave interviews.We also see an undated letter from Tom McGuinness of Manfred Mann’s band discussing auditioning rare Dylan tracks with Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman. (Mann produced the quartet Colson, Dean, McGuinness, Flint’s superb 1972 LP Lo & Behold containing ten Dylan obscurities.)

So how is this box different from the 1975 album or various Great White Wonders? The 1975 set’s overdubbing and Band-penned tracks without Dylan have been removed. The box’s “Don’t Ya Tell Henry” has Dylan singing lead. Some bootlegs’ ballads such as “Percy’s Song” and “The Death of Emmett Till” aren’t present since they preceded the basement tapes. Actually, the box isn’t totally complete for its time span. Over the years, stretches of a few tapes became unsalvageable. They weren’t intended for release to the general public anyway so the studio set-ups weren’t always ideal. A Wurlitzer organ placed too close to the mic at one session took a toll. (The generally chronological box’s songs with the worst audio are consigned to the final CD.)

By 1967, the mercurial Dylan had left behind the upheaval of “When the Ship Comes In” and “Times They Are A-Changin’” as well as the degradation of “Desolation Row” and “Just like Tom Thumb’s Blues.” His scary narratives on John Wesley Harding and quiet romanticism on Nashville Skyline were waiting around the bend.

Right then – as America erupted in ghetto riots, antiwar demonstrations and reckless drug use – Dylan was enjoying family life in a bucolic setting. Little though he wanted to be a guru, the refrain of “Nothing Was Delivered” could be a motto for both himself and his listeners amid the late ’60s’ turbulence: “Take care of yourself. Get plenty of rest.”

— Bruce Sylvester