The Two Ballads of James Connolly, the Irish Rebel

Introduction

Over the summer, I attended a wedding of two friends at my alma mater in Sewanee, Tennessee. For those of you who haven’t heard of it, Sewanee is a small liberal arts college with some of the most devoted alumni the world over. To meet a fellow Sewanee graduate is to meet a friend, someone who understands the unique beauty and spirit of the place, a school known as Arcadia to its citizens.

At the wedding reception, I stumbled upon two former classmates, John and Wolfgang, adamantly discussing James Connolly. They spoke with such fervor, such passion that I was immediately intrigued, all the more so when they then burst into song: Black 47’s “James Connolly.”

As is ever the case with murder ballads, “James Connolly” struck me by its ability to resurrect the dead. Here we were in the middle of the Cumberland Plateau at a wedding, and suddenly the song transported us to Ireland, to Dublin.

Here, I will write about two ballads involving the death of James Connolly. The first was written by Irish folk-revivalists The Wolfe Tones in the early 1970s; the second came decades later, a response of sorts written by the New York-based Black 47. The ballads present two very different pictures of Connolly and his death, and bring into light the ways that tributes are not always a reflection of their subject so much as reflections of their authors.

Easter Uprising and James Connolly

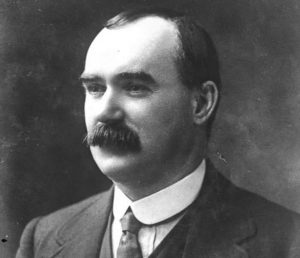

James Connolly was a prominent Irish socialist and political theorist. He was born in Scotland to Irish parents who had moved there, and spent years studying Marxism and socialism in Scotland and America before focusing on Irish independence. He was the leader of the Easter Rising, an anti-British revolution that began April 24, 1916 in Dublin. After sustaining serious injuries on April 27, Connolly helped to orchestrate a treaty on April 29, effectively ending the attack. He died by firing squad May 16th, 1916, while he was still recovering from his battle wounds. This contributed to the ire of his supporters, as he purportedly sat in a chair throughout the proceeding because he was too weak to stand. The Easter Rising and the treatment of the revolutionaries in its aftermath marked a turning point in the public perception of the Irish Republican cause. This ultimately led to the Irish War of Independence in 1919, and the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922.

James Connolly has remained a revered figure of Irish history. Connolly Station, one of Dublin’s two main train stations, is named for him, as is Connolly Hospital Blanchardstown in Dublin. A statue of James Connolly was erected in front of the Dublin Customs House in 1996.

The Wolfe Tones

Our first ballad about James Connolly was recorded by The Wolfe Tones in 1972 on their album Let the People Sing. The Wolfe Tones are a deeply patriotic group, dedicating a portion of their website to the history of the Irish Famine, and taking their name from 18th Century Irish Revolutionary Theobald Wolfe Tone. On their website, they publish a creed of sorts, “We must never forget and we must tell the world so the world can learn from the cruelty of the past and of man’s inhumanity to man.”

This is a sobering effort for sure, and they take their role seriously. Other songs on Let the People Sing include “Sean South of Garryowen,” a folk ballad tribute to a member of the IRA who was fatally wounded in battle in the 1950s, “Long Kesh,” a call to remembrance and civil disobedience for those still in jail for supporting Irish independence, and “A Nation Once Again,” a 19th century ballad written by Thomas Osborne Davis, calling for Ireland to become once more its own country. On this album, The Wolfe Tones are unabashed in their Irish nationalism; revolutionaries are heroes, and they sing to support them.

“James Connolly” is written in absolute support of the Easter Rising, and depicts its main hero in martyr-like terms. This is evident from the first verse, when Connolly’s supporters appear with “their heads uncovered…[kneeling] on the ground.” It is nearly a religious scene, and continually portrays Connolly as a saint: “his life for his country about to lay down.” He meets death “like a true son of Ireland,” facing his firing squad bravely. He then falls “into a ready made grave.” “The cruel deed” is completed and Dublin mourns its fallen son.

Perhaps no verse in the ballad is more stirring or more vitriolic than the one which follows Connolly’s “murder:”

God’s curse on you England, you cruel-hearted monster

Your deeds they would shame all the devils in Hell

There are no flowers blooming but the shamrock is growing

On the grave of James Connolly, the Irish Rebel.

Here we have in quick succession the complete demonization of the English as well as a natural if not divine approval of James Connolly: in the wake of his death flowers will cease to bloom but the Irish shamrock will adorn his grave. The song is incredibly patriotic, mentioning Ireland four times in a five verse song.

Most notably, the song focuses on Connolly’s death. The events of the Easter Rising appear only in the final verse, which reminds us that though the English “tried hard to quell… the spirit of freedom,” James Connolly called out, “No surrender!” Here is no battle song; rather a quiet and steady anthem.